Introduction

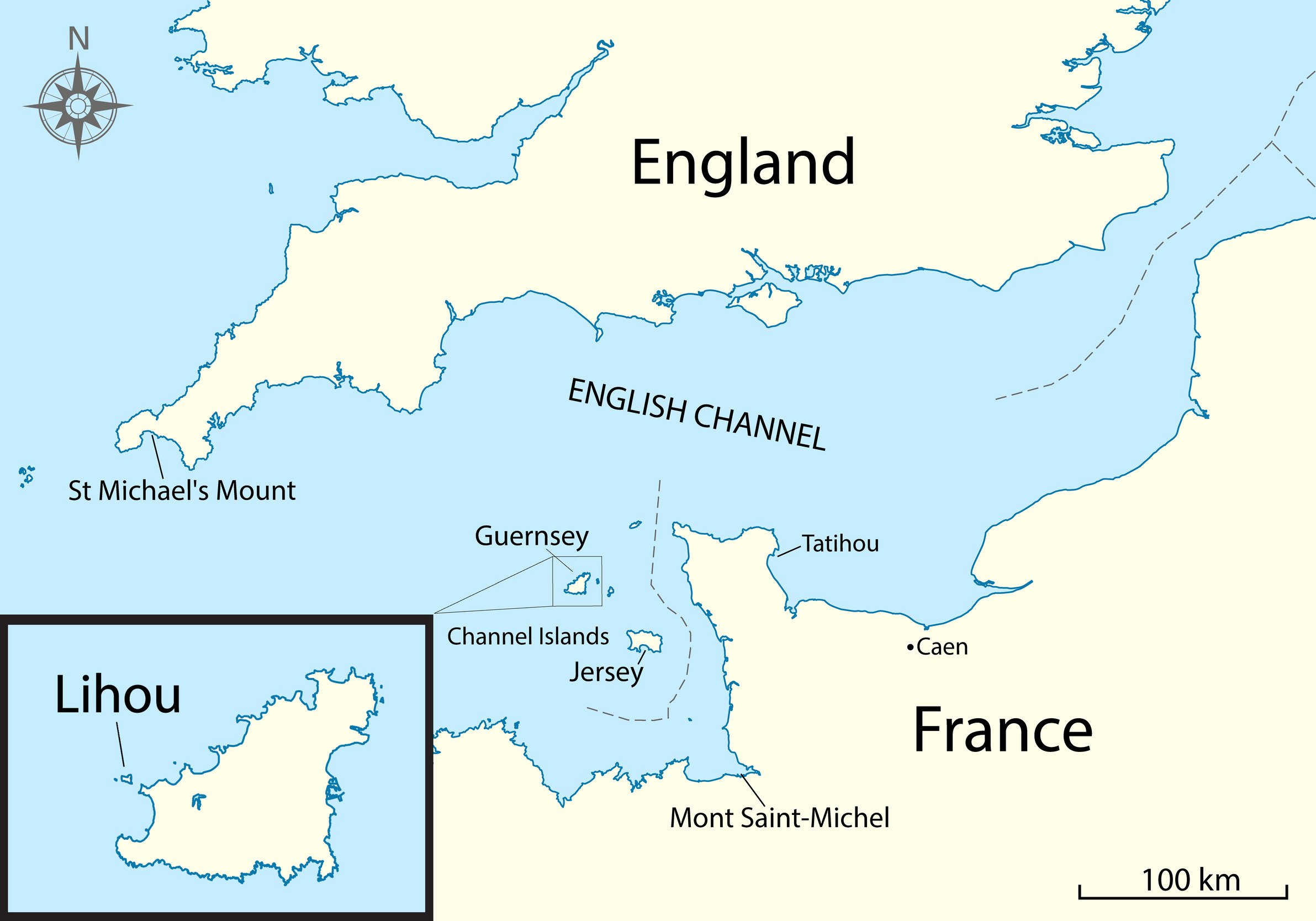

The Bailiwick of Guernsey is a British Crown Dependency and is one of two self-governing bailiwicks in the Channel Islands (the southern-most part of the British Isles and within the Gulf of St Malo to the north-west of France), the other being the Bailiwick of Jersey (fig. 1). The Bailiwick of Guernsey includes six populated islands with varying jurisdictional and proprietary relationships within the Bailiwick (on Guernsey’s islets, reefs and rocks, see Coysh, 1985). There are three jurisdictions: Guernsey (including islands of Guernsey, Herm, Jethou, and the now unpopulated Lihou), Sark (including Brecqhou) and Alderney. Among these islands, Lihou is the primary focus of this article, revealing a cultural history entwined with spirituality and folklore, as well as a physical geography that connects with culture and cultural flows. The amalgamation of these aspects unveils how even a relatively small island can possess a complex existence extending beyond its maritime boundaries. While Lihou is not a major pilgrimage site or tourist destination today, unlike many other islands, its significance in this article lies in revealing historical interconnections across different regions where island geography is inherently linked to religious purposes.

Lihou is a small tidal island just off the west coast of the island of Guernsey (figs 2–4). The name Lihou (occasionally Lyhou) has the suffix “hou,” which is found in the names of several nearby islands, including Jethou, Brecqhou, Burhou (administered by Alderney) and Tatihou (just off the east coast of the Cotentin Peninsula in Normandy in northern France). Lihou has an absorbing history in the study of small islands as sites of religious, spiritual or supernatural exception. Part of the Parish of St Pierre Du Bois (also known as St Peter’s), which is one of Guernsey’s 10 parishes, the 0.15 square kilometre (38 acre) island, which stands as the most western point in the Channel Islands, is accessible from L’Erée headland on Guernsey along a 570 m causeway across a rocky foreshore known as Braye de Lihou, but only for about two weeks every month because of the changing semidiurnal tides (Lihou Charitable Trust, 2023). A narrow tidal gully separates Lihou from Lihoumel, a small rocky islet just to the northwest of Lihou (Borwick, 1989).

This article offers insight into Lihou’s spiritual associations across space and place, contextualising the island through a critical study of literature pertaining to Lihou and related spiritual islands and sites in the Channel Islands and each side of the English Channel. Contributing broadly to the field of island studies, and assembling pertinent secondary literature related to islands and sacred sites covering the Medieval Period (c.500–1500 CE), the article links small islands and their historical spiritual connections within a multi-sited archipelagic framework of which Lihou was a part. In other words, utilising a methodology that studies the interconnectedness of islands across different locations in order to understand phenomena that spans different geographical areas (Marcus, 1995). Inspired by contemporary thought in the field of island studies with its broader interpretation of the archipelago (Pugh, 2013; Stratford et al., 2011), and particularly through an analytical framework with transregional and transnational perspectives (Stephens & Martínez-San Miguel, 2020), the article discusses how Lihou was bestowed with a spiritual presence in connection with its geographic features, and is culturally connected to similar islands and other locations across disjunct archipelagic space. In this context, this article is theoretically inspired by archipelagic theory, which emphasises interconnectedness, relationships and fluid boundaries between islands, island groups and islands and mainlands. For example:

The archipelago is a conceptual tool too little drawn upon. Yet, it could be so useful to break out of stultifying and hackneyed binaries; privileging instead the power of cross-currents and connections, of complex assemblages of humans and other living things, technologies, artefacts and the physical scapes they inhabit. (Stratford et al., 2011, p. 125)

As island studies scholar, Philip Hayward, comments in connection with his study of the comparable tidal island of St Michael’s Mount: “There is a common association of remote, inaccessible and minimally inhabited places with spiritual ‘energies’ and related senses of holiness” (2024, p. 1). Therefore, while Lihou may be the focus of this article, it is necessary to frame this island within a multi-sited archipelago of interconnections and similarities as a way of comprehending the island not only on its own terms (McCall, 1994), but also within a cultural archipelago of the broader island networks of which it is a part.

In the field of island studies, sacred islands have featured in many ways. As well as archaeological surveys of sacred island sites, scholars have explored such islands from perspectives such as their place within a nation’s mythological origins (H. Johnson, 2021a, 2021c, 2022) or through a decolonial lens (Luo & Grydehøj, 2017). Further, Fisher (2014) uses the metaphor “island” in the Chinese Buddhist setting to refer to religion in terms of being “mostly confined within isolated spaces that function as religious islands in a larger sea of secularism” (p. 204). While the current article focuses on Lihou and compares this small island with several culturally connected islands within the English Channel, extending the study further afield reveals other islands with similar spiritual associations. For example, exploring the monastery of Lindisfarne (Holy Island) in the North Sea off the northeastern coast of England, Petts (2019) offers a study of the early medieval tidal world where small, insular islands were “utilised as ecclesiastical sites” (p. 41), and “how tidescapes became constituted in the context of early medieval monastic sites” (p. 42). Just as scholars in the field of island studies have stressed the significance of “sacred landscapes and insular [or isolated] identities” in small island cultures (Papantoniou et al., 2022; Royle, 2001), Petts mentions the importance of “living and thinking tidally” (2019, p. 48), and notes other such small islands more broadly where insularity was important for religion, including Gallinara, Lérins, and various other island sites from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf. In particular, “along the Atlantic coasts the presence of churches or monasteries on specifically tidal islands was common, examples including Locoal, Mont St Michel, Noirmoutier (France), Omey Island, Inishkeel (Ireland), Brough of Birsay, Eilean Chaluim Chille (Scotland) Caldey Island and Llangwyfan (Wales)” (Petts, 2019, p. 42). But the link between insular islands and religion is widespread, especially in Christianity, and is such that there are a plethora of such sacred isles (Dugdale, 1846; H. Johnson, 2021a; Luo & Grydehøj, 2017; Rees, 2020; Schön, 2020; Stokes, 1891). Indeed, such was the importance of insularity to religious thought that “in the corpus of early Christian writings . . . in particular in early monastic sources from the 4th to 6th cent. AD, islands and narratives about insularity play a distinct role” (Schön, 2020, p. 56).

What is significant in this article is the number of small (tidal) islands as religious sites on each side of the English Channel and in between, and also the spiritual connections between them. As such, this study must consider Lihou through a multi-sited geographical lens. That is, within the cartographic sphere of this study, people and their ideas circulated within a disjunct archipelago of spirituality where the geography of specific islands helped form a network of relatively distant islands and related spaces.

With such a perspective on land, sea and space, Lihou is foregrounded as a location of historical significance that linked with islands across a larger archipelago of related sites. Yet, Lihou was abandoned in the contemporary era without the wide-reaching touristic interest of some larger sites such as Mont-Saint-Michel in northern France and St Michael’s Mount in southern England, which are located on opposite sides of the English Channel and have spiritual interrelatedness with Lihou. These associations pertain to small tidal islands as religious locations, connected across a multi-sited archipelago of spiritual significance.

The article divides into two parts. The first outlines Lihou’s priory, setting the scene of the study and focusing on three distinct spheres of the island’s relevance in the present day: Lihou Priory, Lihou in folklore and Lihou in contemporary culture. The second main part of the article extends its geographical reach to show Lihou within a multi-sited archipelago of spiritual islands, connecting not only to its Guernsey mainland, but also to other islands and relevant sites across the English Channel and within the Gulf of Saint-Malo. With a history rich in religious associations and cultural significance not only for Guernsey but also other islands and cultural sites, Lihou has received little attention outside archaeological discovery (e.g., Sebire, 1996). This article aims to extend the study of Lihou beyond its physical borders, focusing not only on the island’s sacred associations but also relating to the idea of multi-sited archipelagic connections.

Lihou Priory, Folklore and Contemporary Culture

Lihou Priory

Lihou is the site of a twelfth-century Benedictine priory, known variably as Lihou Priory, Priory of St Mary of Lihou and Priory of Notre Dame de Lihou. This icon of the Catholic Church, which is now in ruins with only the remains of some of its walls surviving (fig. 5), would have been a dominant structure on the particularly low-lying island, and clearly visible from the L’Erée headland on the Guernsey mainland and to passing vessels. Having stood for several centuries, the priory was dissolved in 1536 when Henry VIII disbanded monasteries, and the priory’s physical demise finally came in 1759 (the Times notes 1793 – “Monastic Ruins For Sale,” 1947) when the Governor of Guernsey, Lieutenant-General John West, ordered that the priory be destroyed to prevent Lihou being a possible landing point for attack by the French during a period of Anglo-French hostility (MacCulloch, 1903, p. 173). At this time, during the Seven Years’ War (1756–63), Guernsey and the other Channel Islands existed under the ever-present threat of attack by the French and were heavily fortified by the English.

The construction of a priory on Lihou is similar to other examples of small islands becoming sacred sites, a process of which is seen as separating the sacred from the profane (McGrath, 2021, p. 81). With a large number of small islands with similar sacred features in northern Europe and in many other part of the world (Luo & Grydehøj, 2017), such a connection points to a particular island lure as a space of sanctuary (Baldacchino, 2012). While the exact reasons for constructing a priory on Lihou are unknown, except that the small island’s tidal features were similar to other small tidal islands in the English Channel and beyond (e.g., Mont-Saint-Michel and St Michael’s Mount), what is clear is that this island’s priory would have been a prominent geographical feature on such a small island. Further, the action of crossing the narrow channel (either by boat or by foot at low tide) to reach the island bestowed a sense of liminality on those making the short journey (Turner, 1969) – that is, passing over a narrow yet distinct tidal zone to reach a location that is physically disconnected from its mainland (i.e., the island of Guernsey). Additionally, the nearly flat island is particularly small, which enhances its sense of separateness and insularity. On the island, the monks and servants lived in a sacred location intentionally disconnected from the profane Guernsey mainland.

Constructed in several phases until the fifteenth century, limestone imported from Caen in France was used to build the priory. This underscores the ongoing close relationships between the Channel Islands and France. The religious site on the island consisted of a Priory church and an adjacent Monk’s house, and various artefacts have been collected from the island dating from Roman to Priory times, as displayed in Guernsey Museum (Walls et al., 2018). By the fifteenth century, the Priory’s links to both France and England became contested as a result of territorial and religious claims (Thornton, 2012, pp. 9–28, 30–31).

Lihou’s priory created a physical and religiously powerful symbol for Lihou. The island’s cultural history is often understood in relation to the priory, with its hegemonic existence rising from the low-lying island and extending its verticality in a symbolic way, occupying a presence on and beyond the island through the Catholic faith. As an emblem of sacred islandness, which refers to the spiritual significance attributed to islands through ritual, pilgrimage or as places of worship, Lihou’s priory offers a cultural history and religious heritage that laces the island space with cultural meaning, historically and in the present day, that interconnects religiosity with islandness, which, as Grydehøj (2018) points out in connection with Lindisfarne’s sacred significance, “infuses it with meaning and allows it to comprehensively occupy its own space” (p. 3), and in this case a relative smallness and isolation.

Lihou in folklore

There are further cultural aspects pertaining to myth and identity that help show how Lihou has gained a new identity in the present day in connection with its history of religious and pagan associations. In a dialectical relationship between good and evil on Guernsey, “it is almost certain that the [Lihou] Priory was built as a challenge to pagan worship. According to legend, witches who met at the nearby Le Catioroc on Guernsey found the Priory a great source of irritation and dread” (States of Guernsey, 2015). In addition, “it is said that the witches even defied the influence of ‘the Star of the Sea,’ [the Virgin Mary] shouting in chorus while they danced, 'Que, hou, hou, Marie Lihou’” (MacCulloch, 1903, p. 122). While it is unknown if witchcraft ever existed on Lihou itself, its presence on the Guernsey mainland helped show the dominance of Catholicism with the construction of the Priory while at the same time acknowledging the presence of paganism. Le Catioroc is just a few kilometres from Lihou and is the site of Le Trépied Dolmen, a neolithic tomb and one of many found on Guernsey and in the Channel Islands more broadly.

Outside of Lihou’s connection with the Catholic Church, Lihou is found in local Guernsey folklore. For example, there are accounts of fishermen saluting the small island as their vessels passed by the rocky coast. As noted in a collection of Guernsey folklore, Lihou “was always considered so sacred a spot that even to-day [as of the nineteenth century] the fishermen salute it in passing” (MacCulloch, 1903, p. 123). While one might connect such acknowledgement to the authority of Lihou Priory (or at least remembering its authority), this type of ritual maritime behaviour was also found in relation to other nearby offshore sites. For example, fishers were known to salute rocks around Guernsey’s rugged coast, as well as lowering their topmasts when passing Lihou (MacCulloch, 1903, pp. 146–147), which might be compared to a type of physical acknowledgement comparable to saluting. Furthermore:

There is also, in the neighbourhood of Lihou, a rock called “Sanbule,” a very dangerous place for ships , and sailors say that underneath this rock can be plainly heard the bellowing of a bull, It is conjectured that the “bule” in the name of this cliff is from the English “bull” or the Swedish “bulla,” and san, from the French saint, and that it points to some now-forgotten legend about a holy bull. (MacCulloch, 1903, p. 249)

With several other rocks on Guernsey’s coastline affording the same honour, one wonders about the lore of the sea associated with such ritual behaviour in other locations. For instance, the custom was also known beyond Guernsey and reveals a distinct maritime association. As one early nineteenth-century account points out, “Englishmen have affected the custom of saluting islands or continents which they leave without hope of returning” (Stewart, 1905, p. 514). Such saluting might be seen as behaviour connected with the dangers of the sea, amongst a variety of sea-related superstitions (Bassett, 1885), although with Lihou, the existence of a Priory, or at least its remains, adds a reason for the ritualistic association.

Lihou in contemporary culture

Lihou has been administered in different spheres over the centuries (Thornton, 2012, pp. 25, 31). A more detailed record of owners has been maintained since the early nineteenth century: Eleazar le Marchant, James Priaulx, Arthur Clayfield, Colonel Hubert de Lancey Walters, Lieutenant-Colonel Patrick Wootton and Robin and Patricia Borwick. Some of these residents have stood out in relation to their activities on Lihou. One of the more demonstrative residents was Lieutenant-Colonel Patrick Wootton (1919–2000). He took his role as an islander in an interesting direction that pointed to increased assertion over Lihou’s island identity with the issuing of Lihou island stamps: “from 1961 to 1983, [he] issued five stamps with different values in 1966 to help raise funds for his youth project on the island (Graham Land Stamps)” (H. Johnson, 2021b, p. 12). Connecting to the island’s religious heritage and links to France, “the 4d stamp showed the ruins of the priory in the foreground and with Mont Saint-Michel . . . shown in the background” (H. Johnson, 2021b, p. 12). Of course, Mont-Saint-Michel cannot be seen from Lihou, even though the 4d stamp depicts such a view (the islands are over 100 km apart), but it is the historical religious connection between the two tidal islands that is being symbolised.

Although Lihou’s sacred associations were challenged in the mid eighteenth century due to the physical destruction of the priory, the island’s religious significance has been remembered in the modern era with Lihou becoming a site of cultural heritage based around its priory. In a move to recognise important local heritage, the priory and island were listed as a Protected Monument in 1938 by Guernsey’s parliament (States of Guernsey, 2023).

The cultural importance given to the site continues to the present day, along with increased recognition of the area’s natural environment. In a context where cultural heritage was being given more consideration by Guernsey’s politicians, the States of Guernsey purchased Lihou in 1995 for GBP410,000 (Lihou Charitable Trust, 2023). Considered an important environmental area for conservation, not only because of the priory’s history and clear remains, but also because of the bird and marine life that inhabit the area on and around the island, in 2006 Lihou and the nearby L’Erée headland on mainland Guernsey became part of Guernsey’s first Ramsar site (a Wetland of International Importance – Ramsar site No. 1608). Such recognition, which might be argued in a broader milieu as a (post)modern substitute for “sacred” (Tatay, 2023), while recognising early Christian connections with nature (Rosenbergová, 2017, p. 31), has contributed much to Lihou’s more recent ventures in that the island nowadays enjoys a particularly close association with its environmental features, including new ways of interpreting isolation and the sacred. That is, as part of its environmental importance, Lihou has an active place in local educational activities that emphasise conservationist activities. As the trust that operates the island’s house notes:

The Lihou Charitable Trust is a locally registered charity set up in 2005 to maintain and operate Lihou House for the benefit of the community. It is available to any family, business, special interest, youth or school group who want to experience the beauty and tranquility of the Island when cut off by the tide. During your time on Lihou you will have the opportunity to: learn about the Island’s fascinating history, explore its many-man-made features or just relax, contemplate and enjoy the stunning views. We call this the ‘The Lihou Experience’. (Lihou Charitable Trust, 2023)

While Guernsey’s Environment Department manages the island, the Lihou Charitable Trust took over the lease of Lihou House and has made it available to the public. Of particular interest to the broader field of island studies is the Trust’s statement to offer Lihou as an island “experience”. Other themes about the island are also stressed, including its “beauty,” “tranquility,” “history,” and “view.” Not only does the island have an environmental distinction, but experiencing its features “when cut off by the tide” help emphasise the liminal relationship that such an island has with its mainland, and in particular those experiencing such a disconnection from everyday life on the mainland. It is also with such liminal features that link to the establishment of its priory, which was relatively remote and separated from the Guernsey mainland.

Lihou Within a Multi-sited Archipelago of Spiritual Islands

In the present day, small islands are often found in networks with similarities relating to such factors as conservation or tourism, thereby having a shared purpose that can cross distant islands. For example, in New Zealand, the nation’s Department of Conservation manages over 200 islands of over 0.05 km² with 50 being designated “Natural Reserves” (Department of Conservation, 2024). In a global setting where “nearly one third of [UNESCO] World Heritage Sites categorized as natural heritage are island sites, including more than a dozen sites which are entire islands or island groups” (Kelman, 2007, p. 101), while such islands have their own existence across cultural space, they can also be viewed as part of a conceptual archipelago in terms of their similarities rather than their physical proximity to each other.

A similar way of framing relatively distant islands is through an industry-focused tourism paradigm. There are many small islands that offer a distinct frame of reference to which visitors travel, passing across water in a liminal process that takes them from one space to another (Ronström, 2021; Ruggieri et al., 2022). As with conservation islands, tourism islands can also be compared across disparate space based on the islands’ size and how they are connected to tourism (Reis, 2016).

Similar types of island connectivity are found with Lihou, where the island not only connects archipelagically to its immediate neighbours, but also to relatively distant islands. While Lihou shares with other islands issues relating to conservation, Lihou has some distinct historical spiritual connections with other small tidal islands (and other locations) within the English Channel that can be perceived in terms of a multi-sited archipelago based on having direct cultural links across national borders and a relatively expansive aquatic space. In this context, a study of inter-island physical, aquatic and spiritual relatedness helps in comprehending Lihou as one of several small islands within a sphere of multi-sited archipelagic connections.

Outside of its Guernsey and Channel Island settings, Lihou connects within physical and spiritual frames of reference across both sides of the English Channel to two prominent tidal islands with distinct Benedictine influence: Mont-Saint-Michel in France (about 125 km southeast of Lihou) and St Michael’s Mount in England (about 215 km northwest of Lihou). Together with Lihou, amongst other islands and sacred sites, these tidal islands had a significant religious association during their medieval history, which was underpinned by physical, spatial and tidal similarities. That is, each island is a tidal island of comparable size and has a similar proximity to its mainland (Table 1).

Mont-Saint-Michel (formerly called Mount Tombe) and St Michael’s Mount have a distinctive mound shape, appearing to rise out of the sea (figs 6–7). Indeed, “this natural characteristic encouraged the ritualization of the landscape around [Mont-Saint-Michel]” (Rosenbergová, 2017, p. 33). Lihou, however, is particularly flat, rising marginally above sea level. While one might contrast the physical form of these islands while emphasising their tidal similarities, there is a cultural connection within a sacred tradition that links them in terms of their relationship with the natural elements. That is:

The records of pilgrims visiting any Michaeline sanctuary, depict a strong connection between nature, sanctity and miracles. In pilgrimage narrations, a cave or mountain (or both), the therapeutic function of water or a forest, and natural elements (earthquakes, storms, lighting, thunder, tides…), are always present. In other words, the natural elements often accompany the manifestation of the divine in the pilgrimage narrations about Michael’s sanctuaries. (Rosenbergová, 2017, p. 31).

Each of these islands is vulnerable to the natural elements, connecting to water with similar tidal flows in remote locations. In fact, Lihou’s relative isolation is presumed one of the key reasons why Mont-Saint-Michel established a priory on the island, showing the significance of tidal islands (and other islands) in establishing sacred sites in particular locations (Molyneux, 2016, p. 619).

Mont-Saint-Michel extended its influence to the Channel Islands and England by establishing a physical presence on Lihou and St Michael’s Mount, amongst other locations. In the present era, however, Mont-Saint-Michel’s cross-channel influence has been transformed into religious tourism by association and not by direct authority. For the islands that have extant physical sites for religious practice, spiritual and touristic pilgrimage prevail. However, for Lihou, the island’s religious significance is nowadays as a site of cultural heritage in a setting of environmental sensitivity, each of which indirectly helps foster Lihou’s continued sacred presence.

Lihou Priory was confirmed by Pope Adrian IV (c1100–1159) to the Abbot of Mont-Saint-Michel in 1156 (Carey, 1904, p. 284). The link between Lihou and Mont-Saint-Michel has been described as “a novel complexity” (Carey, 1904, p. 15) in that not only did these two island connections span a large distance across countries and sea, but even within the religious domain there was contested control over religious sites and islands (Guernsey Museums & Galleries, 2024). Such conflict stemmed from competing actors and was particularly complicated with England and France recognising different popes in 1378. The Channel Islands followed the diocese of Coutances (in northern France), which was not the same pope followed by the English, and thereby resulted in England banning such recognition in 1382 (Thornton, 2012, p. 16). Further, as with some of the religious links between Lihou and Mont-Saint-Michel expressed several decades later, there were cases of power relationships that revealed tensions between competing authorities:

The late 1430s and 1440s provide instances of attempts to exercise direct authority over priories, as by Mont-Saint-Michel over Lihou (Guernsey) (where, for example, in 1448 the prior was ordered by the vicaire of the abbey of Mont-Saint-Michel to come to the monastery to purge himself of irregularities alleged against him). (Thornton, 2012, pp. 30–31).

Along the northern French coast, and including the Channel Islands, there are several islands and sites on those islands that had religious affiliation with Mont-Saint-Michel (Bouet, 1973; de Guérin, 1921; du Manoir, 1877; Dubois, 1967; Guigon, 2010; Molyneux, 2016; Rees, 2020). Mont-Saint-Michel’s sister island, Tombelaine, just a few kilometres away, is a tidal island that also has a spiritual history with hermits and an ancient priory, which was founded in 1137 and linked to Mont-Saint-Michel (Rosenbergová, 2017, p. 19). The connection between Mont-Saint-Michel and St Michael’s Mount just off the south coast of southwest England dates from 1067, after William the Conqueror (c1028–1087) gifted the latter to Mont-Saint-Michel as a reward for support in his conquest of England in 1066 (Fletcher, 2011; Hayward, 2024; Hull, 1967). Monks from Mont-Saint-Michel were housed at St Michael’s Mount (Rees, 2020, p. 251), although the link between the two sacred tidal islands ceased by 1383 (Rees, 2020, p. 251). It is with such connections that “the affiliation with Mont Saint-Michel appears to have given SMM [St Michael’s Mount] a substantial degree of holiness-by-association” (Hayward, 2024, p. 3). With such a linkage between these two tidal islands, by extension, Lihou has an archipelagic association with not only Mont-Saint-Michel, but also with St Michael’s Mount.

Spiritual comparisons with other small islands in the English Channel can also be made. While Lihou, Mont-Saint-Michel and St Michael’s Mount are tidal islands, within close reach of their respective mainland, some other small islands with a spiritual connection and remote location offer further evidence of the importance of small islands in religious history.

By 1042, Chausey (a French archipelago just south of Jersey) and the Channel Islands of Sark, Alderney, Jethou and Lihou had been granted to Mont-Saint-Michel (de Gruchy, 1919, p. 19; Delisle, 1867, pp. 19–20; D. H. N. Johnson, 1954, pp. 198–199; Morris, 2023, pp. 124–125). In this Medieval Period, the Abbey of Mont-Saint-Michel founded, or had jurisdiction over, a number of priories in various locations in the Channel Islands, France and England, varying in number and influence depending on changing political and religious associations and jurisdictional boundaries (Gandy, 2020; Long, 2008; Simonnet, 1999). In the Channel Islands, these included sites at Vale, Lihou, St Clement, Lecq and Noirmont (Molyneux, 2016; Thornton, 2012, p. 16). While the latter three were on Jersey (the largest of the Channel Islands) and are not tidal islands, the first two stand out due to their tidal features. That is, until nineteenth-century land reclamation, Guernsey had a distinct tidal flow that separated its northern Vale parish from the other part of the island. While little remains today of its presence at the site of St Michel du Valle (Vale Church), “around 968AD monks from Mont S. Michel founded a Priory and were granted land to maintain an income. The site, like that of Mont S. Michel, formed an island at high tide, until Napoleonic times the only inland water remaining being that of Vale Pond” (Vale Church, 2008). The fact that the northern and historically smaller part of Guernsey was separated at high tide from its southern part offered a tidal feature that added to Vale’s remoteness and was analogous in certain physical ways to the tidal islands of Lihou, Mont-Saint-Michel and St Michael’s Mount.

With such locations, their relative remoteness contributed to their sacred space. As Gillis (2007) has pointed out, “during the Middle Ages the term ‘island’ referred to any remote or isolated place and was often used to describe houses and neighborhoods” (p. 281). In this way, a correlation between remote sites and islands can be made, showing that they were sometimes sacred sites by virtue of their geographical characteristics.

There are also other islands in the English Channel that had distinct spiritual connections. On the French side of the English Channel, there has been a significant impact of religion on small islands. For example:

A string of mid-fifth century churches bearing one or another of these same dedications (often several of them in groups) were to be found stretching up the west coast of between the mouth of the Gironde [southwest France] and the island of Jersey. Most were on islands—the Île d’Oléron, the Île de Ré, and the Île d’Yeu [west France], for instance—but occasionally they were in littoral or estuarine settings. (Gandy, 2020, p. 150)

Such sacred islands are distinguished by their smallness, separation from their mainland and being relatively isolated (Gillis, 2007; Ronström, 2021). Such remoteness had a clear purpose in that it “might have influenced the numerous island-dwelling hermits and cenobitic communities that flourished off the coasts of the Cotentin and north Brittany during the sixth and seventh centuries” (Gandy, 2020, p. 150). After all, remoteness was seen as an ideal place to encounter God (Ronström, 2021, p. 12).

In the Channel Islands, Maîtr’Île, the largest islet in the Écréhous reef to the northeast of Jersey and about mid-way between Jersey and France, and its disconnection from Jersey and France offers a liminal island space in a relatively remote setting that has physical similarities with the aforementioned islands. Indeed, it is with such a liminal, peripheral remoteness that may have attracted the establishment of a spiritual site in this location and in similar island settings. However, the connection to be emphasised with Maîtr’Île is not within a closely grouped physical island chain, nor to a nearby mainland connected by semidiurnal tidal flows, but the island’s existence across aquatic space and between mainlands.

Maîtr’Île has the remains of an early thirteenth-century Cistercian priory (branched from the Benedictines), Saint Mary’s Priory, which was part of the Abbey of Val-Richer in Normandy, France (Rodwell, 1996; Rybot, 1933, pp. 179–180). It “modified an existing early Christian chapel” (States of Jersey Planning and Environment Committee, 1999). In 1203, Pierre de Préaux (c1170–1212), Lord of the Channel Islands, ceded the reef to Val-Richer and stipulated that a priory be built on the island (Baal, 1933, p. 185). It was abandoned in 1413. Baal (1933) offers a study of the site occupied by the medieval buildings on Maître’Île, noting that its location on the island next to a marsh offered a water supply. The site almost stretches the island’s entire width of about 70 m (Rybot, 1933, pp. 178–179).

Also in Jersey is the Hermitage, a (former) tidal islet now joined to Elizabeth Castle in St Aubin’s Bay. It became a hermit’s dwelling in the sixth century, drawing intrigue due to its secluded location and religious associations. An oratory was built in the twelfth century, gaining significance as a revered destination for pilgrimage. But there are also many other island monasteries around the British Isles and northern Europe, as well as other locations around the globe, some of which reveal geographic and cultural connections with religion (Rees, 2020). With the overlay of religious activity onto small island locations, which often share many geographical features, connections between space and place become evident, sometimes spanning relatively large distances. The space of islands, and particularly the space that is formed because of the intersection between mainland and island, the inbetweenness of being removed from one location and existing in a setting that is cut-off by water, whether a tidal island or within aquatic space, creates a place where religious activities have been deemed ideal. Such islands offer geographical sanctuary, locations removed from the profane of mainland society, thereby creating a sense of isolation from everyday life.

Conclusion

This article has considered Lihou in terms of its multi-sited connectedness. Working primarily within the field of island studies, the discussion has necessarily avoided a chronological or broader history of religious influences on islands, such as that of Mont-Saint-Michel or St Michael’s Mount. Rather, the article has foregrounded and assembled key geographic and cultural information that helps show how Lihou is one of several sacred islands, a study of which can help in comprehending connections between islands, geographical locations and religiosity. The case of Lihou is not exceptional within the global field of island studies, but its study in this article has shown its distinction as one of Guernsey’s tidal islands, its similarities with other tidal islands spanning the width of the English Channel from France to England, and some the ways that religion and folklore can have geocultural spheres (i.e., the intersection of geographical and cultural factors) within and across islands and mainlands. Such multi-sited archipelagic space helps show the significance of small islands not only in their own terms, but also in a broader setting of geographic similarity and cultural connectivity.

Within a medieval world view, there was a conception of islands as sacred places. Tidal islands, small islands and similar isolated sites had a geographic attractiveness of relative inaccessibility due to their remote locations. Such locations were distinct sites, but also helped in the formation of relatively distant multi-sited archipelagos, the study of which helps reveal some of the unique parameters of the field of island studies. Lihou is one example, the interpretation of which offers a perspective that expands the field of island studies in new directions.

In this study, focus has been primarily on Lihou’s historical, sacred existence. Limited by the availability of documentary information, the study has interpreted historical accounts and secondary sources in the context of sacred islands and multi-sited archipelagic connections in the English Channel. However, there are topics that warrant further research. These include broadening the study to other sacred islands beyond the English Channel to identify common themes and unique differences in their spiritual significance; investigating the ecological aspects of sacred islands in terms of the interplay between spiritual beliefs, environmental conservation and tourism in the present day; and consideration of effective policy and preservation strategies that might help protect such sacred island sites.

In conclusion, this article serves as an example for comparison with other sacred islands by emphasising the importance of interconnectedness, multi-sited perspectives and cultural preservation. Lihou’s particular geographic and cultural history highlights not only the need to consider sacred islands in terms of the value of documenting unique cultural narratives and practices, but also the importance of examining such islands as part of broader spiritual networks that can transcend cultural or political borders. Such interconnectedness can enhance understanding of shared heritage across space and place, thereby promoting both particular and holistic approaches to island studies.

._edited_version_of_channel_islands_location_map.png)

._edited_version_of_channel_islands_location_map.png)