Introduction and background

Perceptions of home place are influenced by experiences over time and across space. This paper asks how the region of Pomerania is presented in selected German, Polish, and Kashubian literary work describing the years shortly before, during, and immediately after World War II. Focus is placed on the dramatic events of that period portrayed from a child’s perspective, with emphasis on how sense of place and understanding of culture influenced one another in those years of immense change. The texts discussed here range from novels by highly acknowledged prosaists (Stefan Chwin and Günter Grass), through memoirs by non-professional authors, to a collection of originally oral interviews.

The first section of the paper provides an outline of the history of Pomerania in order to give a background the pre-war Nazi period, the war years, and the forced post-war migrations, when uprooting and of the pre-war population of both Pomerania and Eastern Poland took place. The survivors were forced to take root in a fully different geographical, ethnic, and political environment. The Methods section explains the criteria for the choice of research materials, and the subsequent sections are devoted to analysis and comparison of the literary sources, followed by a conclusion.

The region of Pomerania and its complicated past

From the Middle Ages until 1945

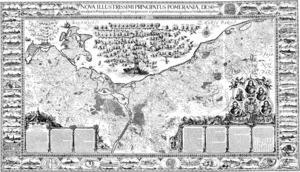

The term “Pomerania” has over the course of time been used in different ways. This is a result of the extremely complicated history of the part of the southern coast of the Baltic Sea that is today divided between Germany and Poland. The Columbia Encyclopedia (Lagasse, 2007) defines the geographical borders of the Pomerania region as the rivers Recknitz, Trebel, Tollense and Augraben in the west, and Vistula in the east, which corresponds quite well to the first detailed map of the Duchy of Pomerania drawn by the cartographer Eilhardus Lubinus (Figure 1) in the beginning of the 17th century (Górniak, 2016). The landscape of the region is dominated by forests, lakes, and sandy beaches of the Baltic Sea. Due to its proximity to the sea, the region has always been attractive to neighbouring rulers for commercial and strategic reasons, especially the harbour city of Danzig/Gdansk.

The brief summary of the history of Pomerania given below is based on Labuda (1971, 1996, 2006), Karczewski (2017), Nowak (2019), Szymkowski (2024), and Walczak (2019).

The Duchy shown on Lubinus’s map was only one of numerous geopolitical formations that existed in the region at the coast of the Bay of Pomerania since early Middle Ages, and that were called “Pomerania” with or without modifiers like “East”, “West”, “Middle”, “Farther”, etc. Before the 10th century, when the area started to be dominated by the Polish rulers, it had been mainly inhabited by Slavic tribes (among them the Kashubians), Baltic tribes and Veneti, but there is also archaeological evidence of German and Viking settlements. Between the 10th and the 17th centuries, Pomerania was split into separate duchies, from time to time partially reunited, then split again. The eastern parts around Gdańsk/Danzig were subject to competition between the Polish kings and the Teutonic Knights, and, after several wars, became incorporated into the Kingdom of Poland in 1466. The middle and Western parts were from the 12th century until 1637 ruled by the local House of Griffin, which albeit being a Slavic dynasty, switched its political sympathies between Poland, Germany, and Scandinavia. The Griffins sometimes exerted considerable impact on European politics: Casimir IV of Pomerania-Stolp, a grandson of the Polish king Casimir III the Great, was considered a serious candidate to the Polish throne, and Bogislav of Pomerania-Stolp, better known as Eric of Pomerania, ruled not only his hereditary coastal realm, but also the Kalmar Union (Denmark, Sweden, and Norway) in the years 1396-1439. The rather successful rule of the House of Griffin ended during the last decades of the Thirty Years’ War with the death of Bogislav XIV in 1637, followed by the division of Western and Middle Pomerania between Sweden and Prussia.

Since then, the German demographic, political, and cultural impact on Pomerania grew steadily, and the native Slavic population became gradually suppressed. In 1795, Poland ceased to exist as an independent state and was divided between Russia, Austria, and Prussia. After the Napoleonic Wars, Sweden lost its part Pomerania to Prussia. Thus, at the beginning of the 19th century, the whole of Pomerania stood under Prussian rule. The Slavic population was marginalized and subjected to a Germanization policy, which intensified after Germany’s unification in 1871, when the “Iron Chancellor” Otto von Bismarck started his Kulturkampf (“culture struggle”) directed against the Catholic Church and all manifestations of non-German identity among citizens of the German Empire.

In 1918, Germany’s defeat in World War I and Poland’s re-established independence actualized the question of the geopolitical status of Pomerania. As can be seen from the brief summary of region’s history above, both countries could claim ethnic, cultural, and political rights to the coast of the Bay of Pomerania. Eventually, the Allies decided on a compromise that was satisfactory to neither the two states nor to the Kashubian population. Gdańsk/Danzig and its immediate surroundings was proclaimed a free city, and Poland was given access to the Baltic Sea through a small strip of land between East Prussia and Middle Pomerania (Figure 2). The existence of the so-called Polish Corridor, and German claims of full control over Danzig were the immediate reasons for the German invasion of Poland in 1939. From then until 1945, Danzig and the rest of Pomerania were incorporated into the Third Reich.

The consequences of redrawing the Central European borders

At the conferences in Yalta and Potsdam in 1945, the Allies decided to move the Polish borders westwards. The eastern territories around Vilnius/Wilno and Lviv/Lwów (around 180,000 km²) were annexed by the Soviet Union; and in the north and west, former Ost Preussen, Silesia and considerable parts of Pomerania (ca 100,000 km²) were incorporated into the new Polish state, which was formally proclaimed independent, but in the reality was governed by a marionette regime established by the Soviets. Figure 3 shows the pre- and post-war borders of Poland.

The decisions by the leaders of the UK, the USA, and Soviet Union caused the largest wave of forced migration in the history of modern Europe. It is estimated that around 2 million Poles from the eastern territories and roughly the same number of Germans from Pomerania were expelled from their houses and the land where their families had been rooted for generations. The terms “Germans” and “Poles” are approximations. Both Pomerania and the eastern borderland of Poland were multiethnic; thus, Kashubians, Ukrainians, Belarussians, and Balts were also affected by the trauma of the post-war population transfer.

As a summary, I quote a fragment from the novel The Tin Drum by Günter Grass:

First came the Rugii, then the Goths and Gepidae, then the Kashubes (…) A little later the Poles sent in Adalbert of Prague, who came with the Cross and was slain with an ax by the Kashubes or Borussians. (…) After the arrival of the Kashubes, the dukes of Pomerelia came (…) They bore such names as Subislaus, Sambor, Mestrin, and Svantopolk (…) Then came the wild Borussians, intent on pillage and destruction. Then came the distant Brandenburgers, equally given to pillage and destruction. Boleslaw of Poland did his bit in the same spirit and no sooner was the damage repaired than the Teutonic Knights stepped in to carry on the time-honored tradition (…) The Husses came, made a little fire here and there and left. The Teutonic Knights were thrown out of the city (…) The Poles took over and no one was any the worse for it (…) Then came the Swedes. They got so fond of besieging the city that they repeated the performance several times. (…) Then Poland was divided in three. The Prussians came uninvited and painted the Polish eagle over with their own bird on all the city gates. (…) then (…) came Marshal Rokossovski. At the sight of the still intact city he remembered his great international precursors and set the whole place on fire (…) This time, strange to say, no Prussians, Swedes, Saxons, or French came after the Russians; this time it was Poles who arrived. The Poles came with bag and baggage from Vilna, Bialystok, and Lwow, all looking for lifequarters (Grass, 1959/1964, pp. 395–398).

The quote above summarizes the history of Gdańsk/Danzig, but the (bitterly ironic) overview can apply to the past of the whole region of Pomerania.

Method: Analysing literary portrayals of uprooting and taking root in Pomerania from a child’s perspective

The Soviet-induced regimes in post-war Poland and East Germany (DDR) censored away any relations of the migration trauma. Thus, until 1989, texts on this topic could only be read in “underground” publications. In contrast, in West Germany, memoirs of the expelled flourished in the 1950s and 1960s. Most of them were written by middle-aged persons, who remembered Pomerania and Silesia as a paradise lost, and seldom addressed the question of the Germans’ responsibility for World War II (Assmann, 2003; Burk et al., 2011; Demshuk, 2013; Flinik, 2009, 2019; Lotz, 2013; Syvenky, 2013). Andrew Demshuk (2013) states that “in the early [post-war] years, Germans (including many expellees) usually neglected to acknowledge that crimes perpetrated by Germans had fuelled the revenge against them” (p. 58). The prose of Günter Grass is among the few exceptions to that rule.

In Poland, the topic of the loss of the eastern territories and the Soviet war crimes could be openly discussed first after the democratic breakthrough in the 1980s. These issues were addressed in the work of renowned authors, like Stefan Chwin, Paweł Huelle, Andrzej Stasiuk, and Olga Tokarczuk, as well as in numerous memoirs by non-professional authors.

For the purpose of the current study, I choose to analyse parts of two novels by highly acknowledged writers, a German-Kashubian and a Polish one, both born in Gdańsk/Danzig: The Tin Drum (Die Blechtrommel, first edition 1959, English translation 1964) by Günter Grass (1927-2015) and Death in Danzig (Hanemann, first published 1995, English translation 2004) by Stefan Chwin (born 1949), and to compare the pictures of pre-war, war, and post-war Pomerania in these novels to stories narrated by German, Kashubian, and Polish non-professionals. The “amateur” texts used here are Kinderland ist abgebrannt by Klaus Zander (The childhood land is burnt down; German, 2011), Jak to przóde biwało by Stefan Fikus (How it was back then, Kashubian, 1996), and Przesiedlona młodość by Paweł Żmuda (Displaced youth, Polish, 2013). The latter is based on oral interviews with post-war inhabitants of Pomerania. Out of them, I chose those told by informants born between 1920 and 1950.

Quotations from The Tin Drum and Death in Danzig are elicited from the English translations by Ralph Manheim and Philip Boehm, respectively. Quotes from the other German, Kashubian, and Polish sources I translate myself, retaining non-normative grammatical and stylistic features where they are present. In cases where a verbatim translation could be too ambiguous or incomprehensible for the intended readers of this paper, explanations are added in square brackets.

I apply the following criteria for the choice of texts:

-

the authors were born between 1920 and 1950 in either Pomerania or former Eastern Poland

-

they all have witnessed or been subject to post-war migrations from or to Pomerania

-

the original texts were written in the native languages of the authors: Polish, German, or Kashubian.

These criteria aimed at eliciting stories rooted in the authors’ biographies and told from the vantage point of children or young adults, who could not have been responsible for the dramatic events of World War II, but whose lives were inevitably changed by the war and post-war trauma. A child’s perspective is designed to shed light on the issue of uprooting and taking root, with children normally being less biased and closer to the immediate impressions than grown-ups (Steinmetz, 2011). Gawrońska Pettersson points out:

Texts based on the authors’ recollections of their childhood often include vantage point shifts:

An adult author of memoirs writing about his childhood can look at it from the perspective of distance, using linguistic means of expression and knowledge of the world possessed by a mature person, but he can also use the point of view of a child, who is a participant and observer of the presented events, perceiving and interpreting the environment on the basis of his limited experiences. (Gawrońska Pettersson, 2019, pp. 182–183)

Though based on limited experiences – or perhaps thanks to the experience limitation – a child’s perspective gives a rich and nuanced picture of the past that includes details and spontaneous emotional reactions that are often omitted or at least not foregrounded in accounts written entirely from an adult perspective.

Most narratologists and researchers exploring literary genres agree that the boundaries between documentary autobiographies and fictional literature are fluid (Booth, 1961; Czermińska, 2000; Romberg, 1962; Stanzel, 1979; Vogrin, 2003). As stated by Gawrońska Pettersson (2019, p. 181), “autobiography and fiction often overlap: literary (fictional) work is part of the author’s biography, and autobiographies are subjected to more or less conscious literary treatments.” Thus, it seems unnecessary to draw a sharp borderline between fiction that includes autobiographic elements (here, Chwin’s and Grass’s prose) and the memoirs of non-professional authors.

In the following sections, I focus on the point of view of children, although in the analysed texts, elements of an adult’s distant vantage point are sometimes intertwined with the child’s perspective. The most notorious example is the narrator of The Tin Drum, Oskar Matzerath, a boy with a three-year-old child’s body and an adult’s mind. As stated by Valery Vogrin (2003, p. 78), “points of view, like microscopes, can reveal things ordinarily unseen.”

The pre-war, war, and post-war years in the eyes of children

Joanna Flinik (2019), in her study of the memoirs of the expelled German inhabitants of Pomerania, points out two main tendencies in these autobiographic texts: some authors focus on the picture of the idyllic land of their childhood and their safe family homes, and express nostalgia for the childhood utopia, whereas other concentrate on the migration trauma. Most of the memoirs discussed by Flinik are written by people who were young adults or adults in the 1930s. In the texts chosen for the current study, the childhood time is mostly far from idyllic.

The Nazi time in The Tin Drum

Günter Grass’s fictional hero and narrator, Oskar, born in Danzig in 1924, observes and analyses people around him from the moment of birth. The disappointing results make him decide not to join the world of adults: on his third birthday, he decides not to grow anymore. By letting Oskar keep the body of a child, Grass achieves the microscope-type picture, and the hero, whom the adults believe to be a bodily and mentally impaired little boy, gains access to “things ordinarily unseen” (Vogrin, 2003, p. 78). Among them, there is the love triangle involving Oskar’s Kashubian mother Anna; her husband, the German Alfred Matzerath; and her cousin Jan Bronski, who identifies himself as a Pole despite his Kashubian origins. This love triangle, which causes Oskar’s uncertainty as to which of the two men is his father, can be interpreted as symbolizing the complicated identity issues in Pomerania: the fates of the three main ethnic groups are intertwined, and the choice of loyalty ambivalent. The question of national and ideological loyalty becomes a burning issue when the Nazis appear on the political scene. Prior to the Nazi period, Oskar’s two “fathers” were tolerant and friendly towards each other, united rather than conflicted by their love for Anna, yet they now find themselves on different sides of the barricade: Alfred joins the NSDAP, while Jan keeps to his Polish identity. Shortly after the outbreak of the war, Jan is killed by German soldiers following the defence of the Polish Post Office in Danzig.

Other elements of the microcosm in which Oskar lives (consisting largely of the family house, the neighbourhood, and some streets in the city centre) also undergo dramatic changes. A gentle musician transforms into a devoted Nazi and a sadistic tormenter of animals, a homosexual neighbour commits suicide, and so does the Jewish toy merchant on Kristallnacht in 1938. Grass sums up these traumatic events in a poignant fragment that imitates the rhythm of Oskar’s tin drum:

There was once a musician, his name was Meyn, and he played the trumpet too beautifully for words.

There was once a toy merchant, his name was Markus, and he sold tin drums lacquered red and white.

There was once a musician, his name was Meyn, and he had four cats, one of which was called Bismarck.

There was once a tin drummer, his name was Oskar, and he needed the toy merchant.

There was once a musician, his name was Meyn, and he did his four cats in with a fire poker.

There was once a tin drummer, his name was Oskar, and they took away his toy merchant.

There was once a toy merchant, his name was Markus, and he took all the toys in the world away with him out of this world. (Grass, 1959/1964, p. 196)

Broken toys and violently interrupted children’s games are recurrent motifs in The Tin Drum (Grass, 1959/1964, pp. 195–196, 232–233). They are accompanied by scenes of real death and destruction. Markus’s suicide in his vandalized toy shop, the wastage of the Polish Post Office and the death of its defenders, symbolize the annihilation of the Jewish inhabitants of Danzig and those Slavs who openly declared themselves as Poles. The phase of physical elimination of Jews and people openly declaring Kashubian or Polish identity in 1938-1939 is followed by a process of more or less forced uprooting of the remaining Slavic population. This is, again, mirrored in Oskar’s microcosmos. Oskar’s Slavic relatives are either registered as Germans by an automatic bureaucratic procedure applied to those born before World War II (“The old folks had been turned into Germans. They were Poles no longer (…) German Nationals, Group 3, they were called”; Grass, 1959/1964, p. 301) or chose to declare loyalty to Germany out of fear for persecution (“Hedvig Bronski, Jan’s widow, had married a Baltic German (…) Stefan Bronski (…) had volunteered, he was now in the Infantry Training Camp”; Grass, 1959/1964, p. 289). Peaceful coexistence of Germans and Slavs was no longer allowed in the time of Nazi military success.

The early war years in Zander’s Kinderland ist abgebrannt

Klaus Zander’s earliest memories come from the time when the author was a three-year-old boy, which means that he was the age of Oskar Matzerath when the latter decided to no longer grow. However, the narrator of Kinderland ist abgebrannt is not a fictional character equipped with magical abilities. The author stresses that his book is based on authentic experiences (Zander, 2011, p. 5). Nevertheless, it should be kept in mind that “the interpretation of each experience is the interpretation of a memory of that same experience” (Steinmetz, 2011, p. 19).

Zander was born 1937 in the medium-sized town of Stolp (today’s Słupsk), located between Danzig and Stettin. His parents belonged to lower-middle class (again a parallel to Grass’s Oskar). The first conscious glimpse of memory the author relates is a walk with his parents in the fields and woods by the river Stolpe. He remembers his father wearing the Wehrmacht uniform. This must have occurred in the spring of 1941 since his father would soon need to leave for war in Russia. Klaus and his mother say farewell to him at the train station. The father’s departure makes the little boy ponder three words he does not understand: “war”, “leave”, and “Russia”: “Daddy is in war and has no leave (…) Thus, leave was for me an abstract concept that stood between me and my dad” (Zander, 2011, p. 8). “Around the bend, where the train could still be seen, there could be Russia, I thought” (Zander, 2011, p. 13).

Despite missing his father, Klaus can enjoy a relatively happy childhood for a short time. The author’s memories of the neighbourhood, the streets and parks, the surrounding woods, and the nearby harbour in Stolpmünde (today’s Ustka) are exceptionally detailed and vivid to come from a preschool child and make the impression that little Klaus feels a deep connection to his “small homeland” (Gawrońska Pettersson, 2019, p. 187; for a discussion of the notion of “small homeland”, see Śliwińska, 2008).

Eventually, the previously abstract concept of war starts getting more and more concrete as the child’s familiar surroundings change. Bronze monuments disappear from the city squares and parks, and Klaus learns that they will be melted and turned into canons. In the harbour of Stolpmünde, Klaus sees submarines, and in the streets, he encounters wounded soldiers. The boy is deeply shocked when he overhears one of the soldiers talking about a mass execution of civilians in Poland:

In my imagination, I saw the square in the little Polish town in front of me. The small houses that surrounded the square with the cobblestones, same pavement as in many streets of Stolp. They were the same houses as the houses here. (Zander, 2011, p. 83)

The issues of ethnicity or nationality do not seem to preoccupy the child’s mind at all: his spontaneous reaction to the horrid story is empathy and compassion with people who lived in a “small homeland” similar to his own. As for his own and his relatives’ identity, they think about themselves first as Pomeranians and as Stolp-people, and are generally sceptical of, even negatively inclined toward, Hitler and the war: “It was a typical Pomeranian view that big times are not good for little people” (Zander, 2011, p. 27). This attitude culminates when the family receives the message that Klaus’s father is missing at the Russian front. It is significant that Klaus’s mother’s despair and anger are not directed against the Russians: “I saw her read [the letter], scream, cry, curse Hitler (…) I heard the phrase ‘murderer of my youth’ over and over again; by those words she meant Hitler” (Zander, 2011, p. 18).

The message about the father’s fate is the first stage in the course of events that will soon destroy Klaus’s childhood and cut him off from his small homeland of Stolp.

War experiences of young Pomeranians-to-be

Paweł Żmuda’s Displaced Youth (2013) is based on oral interviews with inhabitants of villages nearby Słupsk/Stolp. The stories are rendered verbatim, without stylistic or grammatical corrections. Most of the informants were born in Polish former eastern and southeastern territories, conquered by the Red Army after September 17th, 1939, formally incorporated into the Soviet Union in 1945, and today part of Lithuania, Belorussia, or Ukraine.

All but one of the informants identifies as an ethnic Pole. The other comes from the Lemko minority, originally inhabiting a mountain region in southeastern Poland. Their recollections focus on war and post-war years, but the Lemko informant Maria Medwid (born 1931) gives the following account of her multiethnic home village before September 1939:

We were all the same, the Lemko region and that’s it. It wasn’t [an issue] if someone was a Pole, or any arguing, no. People lived their lives, everything was fine. It wasn’t like that back then, that you were a Ukrainian or a Lemko, but everyone lived the same way. Everyone talked the same way, everyone went to the same church, children went to the same school. Children were, as children are, we fought, we called each other names, but only for fun, not: “you’re a Pole or something else.” (Żmuda, 2013, p. 89)

What left the deepest traces in the minds of former inhabitants of the eastern borderland were the deportations to Siberia and the atrocities committed by the Soviets, and, in case of people from the southeastern regions, by Ukrainian ultranationalists. Eugenia Kosińska, born 1927 in the Wilno/Vilnius region, remembers:

In 1939, the Russians attacked our country, and already in 1940, they began to deport wealthy farmers to Siberia (…) We were on a train for a month, in the railway cart there was only some straw to sleep on and a hole in the floor to relieve ourselves, then we arrived in the town of Pervouralsk. There, in winter, there is much snow and terrible cold. We worked in a factory that produced weapons, they made mines and the like (…) There were a lot of us, many of us died of cold and hunger. We ate cabbage and a small slice of bread, thin soup, if they gave us some. (Żmuda, 2013, p. 38)

Zdzisław Iwanek, born 1932 in the region of Lwów/Lwiw, relates yet more atrocious events. He refers to the Katyn massacre in April and May 1940, when more than 20,000 Polish prisoners of war were killed by the Soviets, and to the murders committed by UPA, Ukrayins’ka Povstans’ka Armiia, a Ukrainian ultranationalist paramilitary formation:

When the Russians came, my father was imprisoned. And before that, the Russians took my uncle to Katyn and killed him there. My uncle’s sister married a military officer. They [the Russians] took him and there was no trace of him left. The family were even afraid to search for him, to ask questions about him (…) Later, when the UPA came, if a man had a Polish wife, he had to kill her, and if he didn’t, they both were murdered. Or if a woman had a Polish husband, it was the same. I saw with my own eyes how they murdered (…) One man didn’t kill his wife, and they cut off his tongue, gouged out his eyes, and murdered both of them. (Żmuda, 2013, pp. 20–22)

A multitude of similar, often yet more drastic stories can be found in Polish documentary and memoir literature. The inhabitants of the former Polish eastern borderland had been subject to brutal uprooting before those who survived were forcibly relocated to Silesia and Pomerania.

1945: The childhood land is burnt down

At the end of 1944, it was obvious that the final defeat of the Third Reich was inevitable. The Red Army was approaching Pomerania, and the civilian population, knowing about the atrocities committed by the Soviet soldiers, were sinking into despair and deadly fear. Zander (2011) states, “It was a time when children no longer asked questions” (p. 117). To the list of the strange words about which the boy pondered (“war”, “leave”, and “Russia”), the word “end” was added: “Many feared that this would be the last Christmas before the end. (…) I was constantly preoccupied with the question, what the end was, but I didn’t dare to ask anyone” (Zander, 2011, p. 125).

Some civilians tried to escape by the sea (Chwin, 1995/2004, pp. 30–51; Zander, 2011, p. 135). Grass’s novelette Crabwalk/Im Krebsgang (2002/2002) is devoted to this theme (for an analysis, see Mews, 2008). However, there were not enough boats, and the roads to the harbours got blocked by the refugees’ cars and wagons. Some people were so desperate that they chose an irreversible way out: “Suicide was a frequent topic of conversation back then (…) Later, the consequences of this last ‘escape’ of many Pomeranian citizens could be found again and again and everywhere, in the forests, on riverbanks, in deserted houses” (Zander, 2011, p. 129).

The arrival of the Soviet troops was marked by apocalyptic fires. Destruction by fire is announced already in the title of Zander’s memoirs: Kinderland ist abgebrannt is a paraphrase of ‘Pommerland ist abgebrannt’ (‘the country of Pomerania is burnt down’), a verse from an old German nursery rhyme. The seven-year-old Klaus witnesses the charred remains of his beloved Stolp:

When we turned into Long Street and entered the Old Town, we were horrified to see that there were no houses left (…) Only smoking remains of walls, charred beams in which some people poked around here and there. We walked on (…) and saw only smoking ruins to the right and to the left. (Zander, 2011, pp. 145–146)

In the two novels by Grass and Chwin, the reader is given pictures of burning Danzig that share many stylistic features: both express the totality of destruction through use of long, syntactically parallel phrases containing lists of streets, architectonic details, and items of everyday use being devoured by fire. It is worth noting that in both descriptions, the same parts of the city are mentioned, and even some specific places referred to are the same: the ramparts, Hound Street/Hundegasse, Old City Ditch/Stadtgraben:

Hook Street, Long Street and Broad Street, Big Weaver Street and Little Weaver Street were in flames; Tobias Street, Hound Street, Old City Ditch, Outer City Ditch, the ramparts and Old Bridge, all were in flames (…) What bells had not been evacuated from St. Catherine, St. John, St. Birgit, Saints Barbara, Elizabeth, Peter, and Paul, from Trinity and Corpus Christi, melted in their belfries and dripped away (…) In the Big Mill red wheat was milled. Butcher Street smelled of burnt Sunday roast (…) In Baker Street the ovens burned and the bread and rolls with them. (Grass, 1959/1964, pp. 378–379)

The wardrobes full of linens safely arranged on their shelves like Miocene strata at the Mitzners’, the Jabłonowskis’, the Hasenvellers’; the oak bed frames with carved headboards at the Greutzers’, the Schultzes, the Rostkowskis’; the tables napping under their star-patterned crochet throws at the Kleins’, the Goldsteins’, the Rosenkranzes’; the brick walls by the old ramparts along the Stadtgraben, the stuccowork adorning the porches on Hundegasse, the iron gratings on Jopengasse, the gilded portals of Langer Markt, the granite balls guarding thresholds on the Frauengasse, the copper gutters, window frames, doorjambs, statues, roof tiles – all of this was drifting toward the flames like so much dandelion fluff. (Chwin, 1995/2004, p. 27)

In The Tin Drum, the annihilation and uprooting of the pre-war Pomeranian population culminates in four scenes that are both realistic and symbolic: 1) the vandalization of the toy store and the suicide of the Jewish toy merchant; 2) the destruction of the Polish Post Office and the death of Jan Bronski; 3) the family gathering at which Oskar realizes that his Kashubian-Polish relatives have declared German nationality (“All took great pains not to speak about Jan Bronski”; Grass, 1959/1964, p. 289); 4) the final fire, followed by Alfred Matzerath’s death. In Death in Danzig, the same process is condensed into the fire scene, where the author deliberately mixes Jewish (Goldstein, Rosenkranz), German (Hasenveller, Greutzer, Klein, Schultze), and Polish (Jabłonowski, Rostkowski) surnames. The topographical details stress that the families had lived in the same neighbourhood, which was turned to ashes together with their pre-war lives (for an in-depth analysis of the symbolism of everyday objects in Chwin’s novels, see Kedzierska Stimmel, 2012).

Not only in Pomerania, but also in Eastern Poland, fires signalled the final uprooting. Many formerly multiethnic villages were burnt down as part of the process of the forced transfer of the population to the west. The oral account by the elderly farmer Maria Medwid (in 1945, a 14-year-old girl) expresses the tragedy as poignantly as the texts of the acknowledged writers do:

They burned everything (…) Half of the village was burned down even earlier. A year earlier. Because people were earlier deported to the Soviet Union, to Ukraine. They didn’t manage to deport all of us, since people fled abroad [by “abroad”, the informant means Hungary]. They [the people] took their cows and horses and ran away, and left their houses. And the army came, an empty village, matches, and that’s it, they burned down [the remaining] half of the village. We had an old, wooden [house]. They burned everything. Only the icons we took with us. (Żmuda, 2013, p. 94)

The migration and the new homes

In the fall of 1945, after the wave of killings, robberies, rapes, and hunger that followed the fires in Pomerania (Flinik, 2019, pp. 169–170; Grass, 1959/1964, pp. 382–383; Zander, 2011, p. 148; Żmuda, 2013, p. 48), the situation seemed to stabilize: food coupons were distributed among the inhabitants, most of the Russians left, and the newly arrived Polish administration and militia tried to establish law and order.

Klaus Zander, back then an eight-year-old boy, is astonished when confronted with the news that his hometown belongs to Poland now: “I didn’t understand what that was all about. What did I have to do with Poland? (…) I believed Poles only lived in Poland, which was somewhere far east” (Zander, 2011, p. 202). An equal astonishment is expressed by two young characters in Daniel Kalinowski’s (2019) theatre play Mój nowy dom/My new home, who, after several weeks on a train, approach the same station where little Klaus Zander bade farewell to his father four years earlier:

H: Stolp? This is supposed to be my new home?

J: It’s Słupsk now. I guess we’re to go off. (Kalinowski, 2019, p. 440)

Despite the appearances of life in the region returning to relative normality, the orders issued by Stalin were clear: the German-Pomeranians were to be expelled to post-war Germany, west of the river Oder. Klaus Zander and his family left their homeland, as did the fictional Matzeraths. A tiny German minority chose to stay, mostly because of family ties and emotional bonds to their places of origin (Flinik, 2019). So did the main character of Chwin’s novel, Hanemann.

The new inhabitants of Pomerania were confronted with the former ones, those about to leave and those who, like Hanemann, preferred to stay. The child narrator of Death in Danzig arrived in Gdańsk/Danzig in his mother’s womb (Chwin, 1995/2004, pp. 69–70), but Żmuda’s informants came to their new homes as teenagers. What is common among their stories is empathy, even sympathy, towards the German Pomeranians. Zdzisław Iwanek says:

The Russians weren’t here anymore when we arrived. Yet the owner, Lady von Hanstein, lived [in the manor]. Her older daughter’s name was Marie, it was the one who wore glasses, and the other one’s [name was] Anne, she had a baby, eight- or seven-month-old. They were very nice and kind, all of them (…) And she [Lady von Hanstein] left without any packages, in clogs. She wasn’t allowed to take her belongings with her. (Żmuda, 2013, p. 25)

The informant Maria Terefenko’s story connects to the rapes committed by Russian soldiers on both German and Polish women (“It was a day of horror for women”; Żmuda, 2013, p. 48) as well as to the suicide wave of early spring 1945, and stresses the fact that the fates of Eastern Poles and Pomeranians had a lot in common:

The owner of this large dairy, as the front approached, he poisoned his family and shot himself, he feared the Soviets that much. Later the Germans were deported from these areas (…) All their belongings they could take with them had to fit into their suitcases. They had to leave a lot of things, the Poles took the things that were left behind, because the Poles came only with suitcases, too. (Żmuda, 2013, p. 47)

The informant Henryk Kowalski also expresses sympathy towards his German-Pomeranian peers: “I was on good terms with those German boys. On the pond near the mill, we sailed on ice floes, or, when it was really cold, we played hockey. A Polish-German team” (Żmuda, 2013, p. 47).

The stories quoted above are fully compatible with the friendly bonds between the German physician Hanemann and his new Polish neighbours depicted in Chwin’s novel (Chwin, 1995/2004, p. 91), as well as with the relations between the Matzeraths and the new owner of their grocery shop who came from southeastern Poland (Grass, 1959/1964, pp. 386–390). Generally, the newcomers did not share the Stalin-established authorities’ hostile attitude to the German-Pomeranians. On the contrary, they saw their own fate mirrored in what was happening to former owners of their new homes, and mostly felt sorry for the expelled. The new and the old Pomeranians were also united by fear of the Soviets.

Where prejudice does exist, it is expressed by Germans against the Poles. One of the characters of Chwin’s novel demolishes his Danzig apartment before leaving it and comments, “You think I could live in the same house once those eastern pigs have stayed here?” (Chwin, 1995/2004, p. 56). German nurses in the hospital where the narrator’s mother works treat their Polish counterparts “as if they didn’t exist” (Chwin, 1995/2004, p. 89). However, such episodes seem to have been exceptions to the rule.

Many Polish newcomers believed that the current situation was temporary, and that the German-Polish-Soviet borders would soon return to their pre-war status (Syvenky, 2013). This thought is expressed by the mother of Chwin’s narrator, little Andrzej: ““We should have Andrzejek learn some German,” Mrs. Ch. had told his husband. “You’ll see, they’ll be coming back, together with the English and the Americans. German will come in handy”” (Chwin, 1995/2004, p. 91).

However, children and teenagers were generally not preoccupied by their parent’s uncertainty concerning the future of Pomerania, and quickly adapted to the new conditions. Chwin’s little Andrzej finds it natural that his world is built up of palimpsests, and that the adults around him come from different places and speak different languages:

Delbrück-Allee was no longer Delbrück-Allee. Now it was Skłodowska-Curie Avenue. The old Volkssturm barracks on the way to the Academy had been converted into a chapel (…) The Academy also employed a number of doctors from Vilna – surgeons from the medical faculty of Stefan Batory University. Mama listed their names with respect: Drs. Michejda, Piskozub, Jóźkiewicz (…) but many of the nurses were German Krankenschwester (…) The Polish doctors liked working with them, perhaps even more than with the Polish nurses. (Chwin, 1995/2004, pp. 88–89)

Żmuda’s informants express the same attitude of acceptance of their new lives. Their accounts of the 1950s and later decades are stories of everyday life with its normal stages: school, work, marriage, children and grandchildren. Many of the new Pomeranians mention that they have stayed in touch with the previous owners of their houses and farms, and that the “old” Pomeranians have visited them several times after the normalization of Poland-Germany relations in 1970. This harmonizes perfectly with observations made by many researchers who investigated the issue of old and new inhabitants of Pomerania and Silesia (Demshuk, 2013; Kedzierska Stimmel, 2012; Lotz, 2013; Syvenky, 2013). However, the overall situation during the Communist rule was not idyllic: the official narration of the government (and, as a consequence, the one mediated by the schoolteachers) was that the Germans (especially these residing in West Germany) were enemies of Poland, and that Pomerania and Silesia had originally been Polish territories. Discussion of the region’s complex history was taboo until the 1980s, as was the question of the Kashubian minority.

Those who stayed: the Kashubians

The presence of the Kashubians in Pomerania is documented from the 7th century AD. The significance of their language in the area is confirmed by the fact that during the Reformation period, prayer books and several religious texts were published in Kashubian, or rather in a mix of Polish and Kashubian (Labuda, 1996, 2006). In the course of the stormy history of the region, the Kashubian population of Western and Middle Pomerania gradually succumbed to German influence, while the Kashubian language and culture remained strong hold in the eastern areas close to Danzig. As already mentioned, even the eastern parts of Pomerania were subjects to Germanization efforts from the 19th century, but the Kashubians strove to maintain their identity. Being Kashubian was marked not only by language and customs, but also by religion: most Kashubians remained Catholic, which distinguished them from the mainly Protestant Germans.

The difficult issues of identity and loyalty among the Kashubians were addressed above in connection to the fate of the Bronski family in The Tin Drum. In fact, even most influential Kashubian activists in the 19th and early 20th century disagreed as to the desired status of their ethnic group and language. The Polish-Kashubian writer Hieronim Derdowski (1852-1902) and his followers represented the opinion that Kashubian was a Polish dialect, and the Kashubians were ethnic Poles, who should integrate their fight against Germanization with the Polish fight for regaining independence. On the other hand, the linguist and Kashubian activist Florian Ceynowa (1817-1881) and his adherents regarded their language as a separate Slavic tongue and stressed the ethnic specificity of the Kashubians. The latter view found confirmation in the work of Polish linguist and ethnographer Stefan Ramułt (1859-1913), who gave archaeological, ethnological, and dialectological evidence for the status of Kashubian as a language related to, but distinct from Polish. Ramułt also published the first acknowledged Kashubian dictionary in 1893.

Most active members of organizations promoting the Kashubian language and culture, no matter which fraction they belonged to, fell victim to the Nazi repressions after the outbreak of World War II. Many were executed in the massacres in Piaśnica near Danzig that occurred between fall 1939 and spring 1940; others were sent to the concentration camp in Stutthof or to forced labour. The fate of those Kashubians who identified themselves as Poles and chose the Polish side in 1939 is exemplified by the life and death of Jan Bronski in The Tin Drum; the dilemmas faced by the survivors resembled those confronting Jan’s widow and son. Members of the same family often fought on opposite sides of the front (Walczak, 2019). The Kashubian writer Stefan Fikus relates in his memoirs:

The last war made a lot of damage to people’s mentality. Those who were supposed to be the good ones, often turned out to be the worst villains (…) The Germans wanted to turn the Kashubians into cannon fodder by force, to plug the holes at the front. My half-brother Bernat was eventually taken to the war, too, although he did everything to avoid it (…) On the Polish side, near Wejherowo and Gdynia, fought Bernat Bizewski’s two brothers, Stach and Bruno. Thus, the Germans had trouble with Bernat, because he made up his mind to do everything to not support the Germans, but to make as much harm to them as possible. (Fikus, 1996, pp. 64–65)

Fikus (1996, p. 104) also mentions concentration camps and forced labour: “Jozef Bigus was a conductor and worked on trains all over the Kashubian land. When the war broke out, he was taken to a penal camp and sent to hard labour in Finland. He suffered hunger and cold.” The defeat of the Germans and the arrival of the Red Army did not mean an end to the suffering of the Kashubians. The Soviets treated them like they treated the Germans, which meant killings, robberies, rapes and deportations of the “enemy of the people” to Siberia. One of the characters in Fikus’s memoirs sums this up as follows:

There were so many sent to Siberia, about whom I don’t know anything today. They suffered for the homeland, and maybe they continue to suffer… They were sent there after the war because they were thinking in Polish. Sure, the Poles had to suffer a lot when fighting for their freedom, and we, the Kashubians, suffered yet more. Now and then, it were the Germans, now and then, the Russians, who hit us on the head. (Fikus, 1996, p. 113)

This utterance expresses similar feelings as does the one by Oskar Matzerath’s grandmother in The Tin Drum. When bidding farewell to Oskar who leaves for West Germany, the old woman says:

“Yes, Oskar, that’s how it is with the Kashubes. They always get hit on the head. You’ll be going away where things are better, only Grandma will be left. The Kashubes are not good at moving. Their business is to stay where they are and hold out their heads for everybody else to hit, because we’re not real Poles, and we’re not real Germans, and if you’re a Kashube, you’re not good enough for the Germans or for the Polacks. They want everything full measure.” (Grass, 1959/1964, p. 416)

Oskar’s grandmother’s words about the Germans and the Poles wanting “everything full measure” were true with respect to the policy employed by the Communist authorities in the first post-war decades. Those Kashubians who strove to maintain their language and ethnic status were seen as potentially dangerous separatists. Kashubian was regarded as a Polish dialect, and children were forced to learn “correct Polish” in schools; their home language was often ridiculed and stigmatized as a sign of lack of education (Janke, 2015).

Kashubian was acknowledged as a regional minority language in 2005. Since then, several academic institutions, publishing houses, and cultural organizations have sought to uncover Kashubian history and maintain this native language and culture.

Conclusions

Both the historical sources and literary accounts referred to in this paper show similar fates for the pre-war inhabitants of Pomerania and those of formerly Polish eastern territories. Both groups witnessed their original multicultural communities being destroyed – physically, socially, and mentally – by dictatorial regimes: the Nazis and the Soviet Communists. Both groups suffered atrocities and were forced to leave their homes without any possibility of return. Among the generation of Pomeranians who were adults in the 1930s there were those who supported Hitler and carried responsibility for the Nazi crimes, but children could not be blamed for the deeds of their parents, and even innocent children were subject to terrible and undeserved experiences. German, Polish, and Kashubian children, who, like the young narrator of Kinderland ist abgebrannt, did not understand the meaning of the world “war”, had to learn it in the most brutal ways imaginable.

The portrayals of the pre-war, war and post-war times in the work of acclaimed novelists Chwin and Grass display many similarities with the accounts given by non-professional writers (Fikus, Zander) as well as with the life stories of Eastern Poles collected by Żmuda. In the different narrations, the reader encounters pictures of pre-war multicultural communities and their dissolution, the culminating points being fires devouring the world of the narrators’ early childhood. Amazingly enough, parts of the different narrations are similar to each other not only with respect to content, but also with respect to wording: there are striking stylistic parallels between the descriptions of Danzig on fire in The Tin Drum and in Death in Danzig, as well as between the reflections on the fates of Kashubians in Grass’s novel and in Fikus’s memoirs.

The topic of taking root in Germany by former Pomeranians is outside the scope of the current paper, but it has been explored elsewhere (Assmann, 2003; Demshuk, 2013; Lotz, 2013; Mews, 2008). The texts analysed here indicate that the process of the young newcomers’ adaptation to their new homeland and their integration with the relatively sparse remaining Pomeranian population was quite successful, although not facilitated by the policy of the Communist regime. Today, the vast majority of the descendants of the “new” Pomeranians identify themselves as Poles but feel strong bonds to their “small homeland” as well. At the same time, Kashubian has been acknowledged as one of the languages of the region, and there is hope for the Kashubian identity to thrive.