Prelude

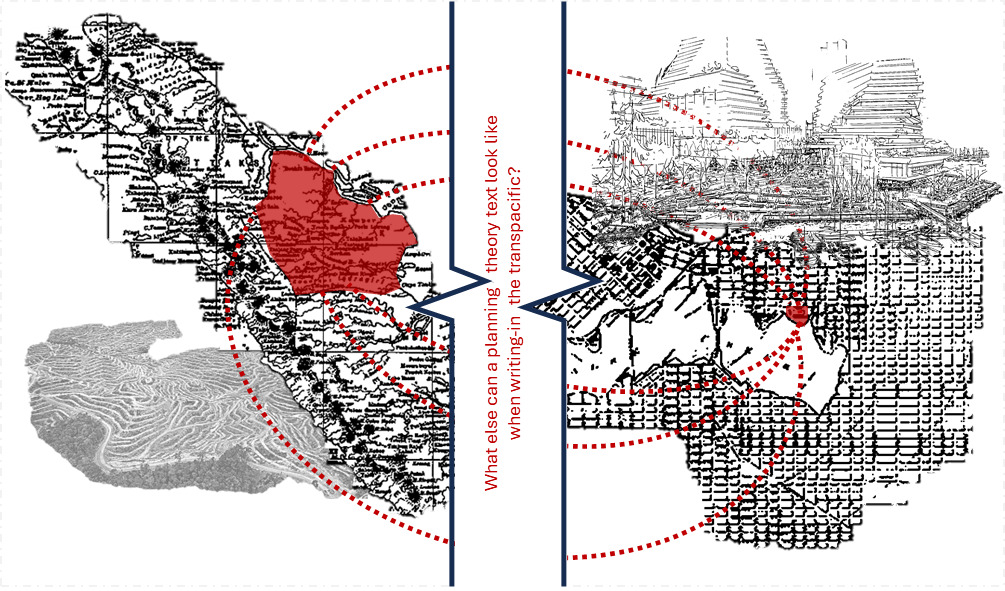

This paper hopes to be an evolving writing experiment that explores the process of writing planning theory of and in the transpacific. Planning theory conventionally aims for the most accurate representation of a site, diagnoses its problems, then proposes plans and solutions. A separation between theorist, text, and site is assumed. This method is tied to planning theory’s roots in governance science, policy analysis, and spatial design. But this paper hopes to explore what else writing theory can do. Specifically, what can be done when writing in the transpacific, affected physically and conceptually by transpacific flows. How is this paper’s concept of ‘writing transpacifically’ changing while writing in the transpacific? Through these questions, this paper’s ‘object’ is both the transpacific and this paper itself.

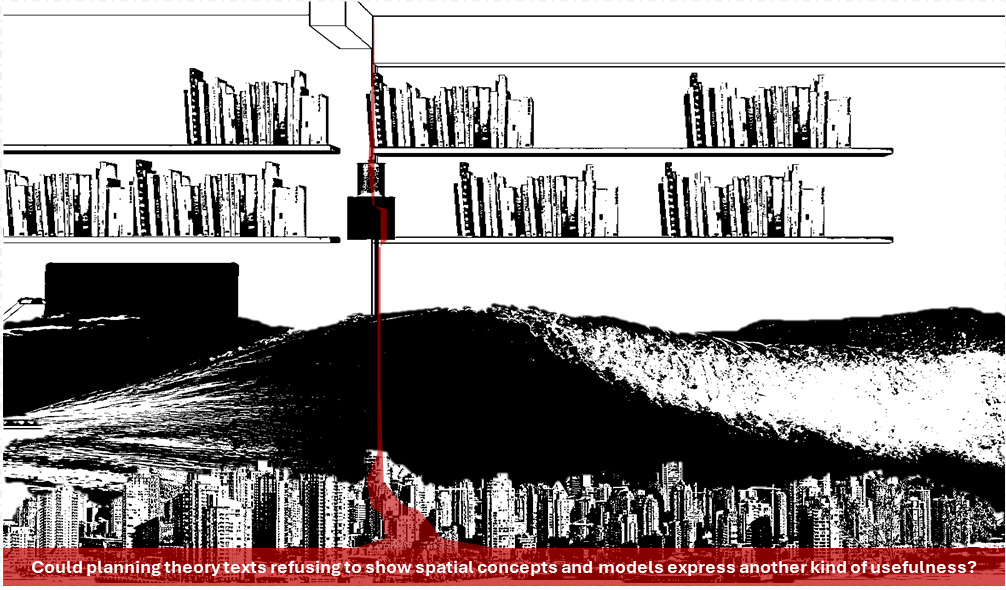

Planning theorists know transpacific financial, material, and labour flows culminating as real estate exacerbate imperial geographies. And the ‘trans’ in the transpacific can be unimageable. If so, how can theory critically engage with these flows and conditions? What might planning theory texts look like doing this? Can they be tools made of concepts and visuals that readers can use to build their own engagement with imperial geographies? This paper aims to be this tool: a quasi autoethnographic document of concepts and visuals.

This idea of a theoretical text as tools is explored in three parts that can read non-sequentially: Part One, Unimageability: ‘Trans’ in the Transpacific’s, briefly explores how theorizing the transpacific unimageability intensifies this condition. This paper distinguishes unimageability from unimaginability. Unimageability suggests thinking can still occur but without accompanying images. Part Two, Theory Yet-to-Come, explores how refusing representation can challenge planning’s imperial desires, and sustain a desire to keep inventing other hopes and connections to keep resisting imperial geographies. Part Three, A Theorist’s ‘I’?, explores how writing can blur the subject-object binary, diffusing the planning theorist’s gaze.

Unimageability: ‘Trans’ in the Transpacific

What else could planning theory’s relation to practice be?

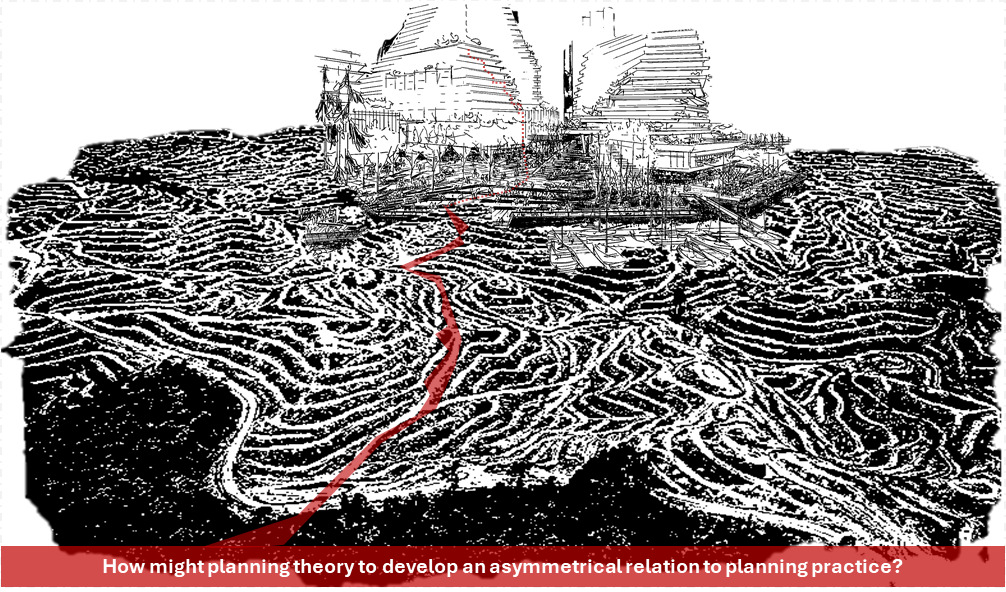

Why should transpacific flows concern planning? Transpacific flows condensing as market condos can impact local ecologies (Haiven, 2022; Khalili, 2020). Sumatran forests are burnt for palm-oil fields to yield the finances to build market condos in Vancouver. However, despite much talk about socio-ecological justice, land-use planning tends to privilege market-oriented advancement over other issues. Often, planning theory contributes to this imperial geography, given the profession and academia’s demands for theory, producing spatial concepts and models to support the market (Levin-Keitel & Behrend, 2023).

How might theory rethink the profession and academia’s demands to make theory produce models and typologies of cities, economies, neighbourhoods, and building, especially ones that privilege the market? This paper suggests, rethinking planning theory’s relation to these demands might proceed with theory writing, refusing its conventional role to make theory mirror practice, or practice to represent theory.

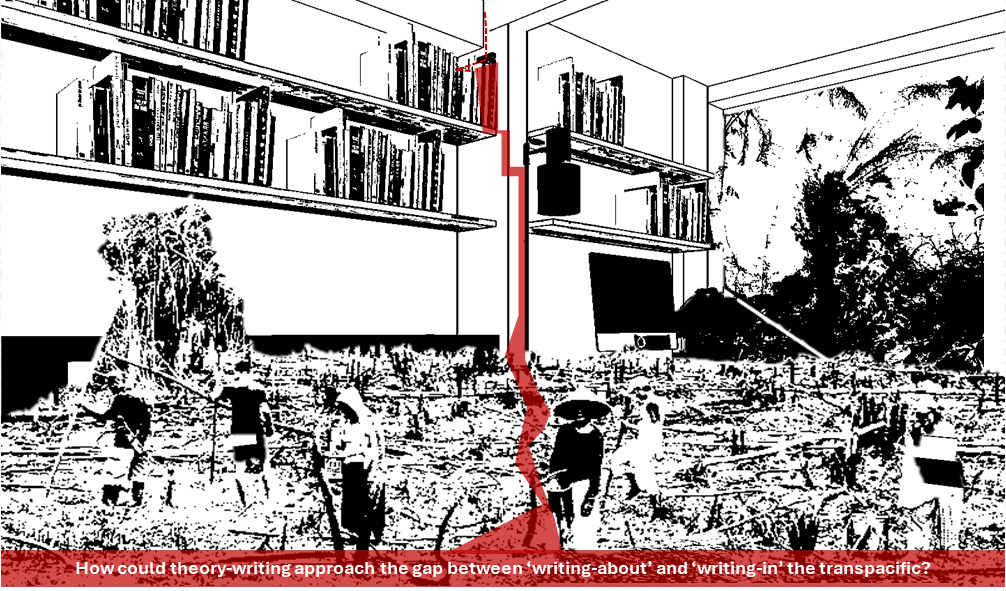

Instead of proposing specific futures, could theory writing (as in this paper) be allowed to ponder how to write and theorise amidst the transpacific flows between Sumatran palm-oil fields, Vancouver waterfront developments, Hongkong’s housing market, etc. Could pondering the gap between ‘writing about’ and ‘writing in’ the transpacific, between theory and site, be useful to critically encounter the transpacific flow that produce ethno-spatial and economic rifts?

Writing transpacifically: unimageability

Could planning theory refusing an image of the transpacific future be an act of writing against planning’s desires to totalise land and sea? This paper proposes the idea of ‘writing transpacifically’—shifting between sites, theoretical frames, voices, etc.—as a way of refusal. These shifts might potentially make these descriptions of sites, voices, ideas not add up to a transpacific totality. A grounded position of writing, in a grounded sites like Hong Kong or Vancouver, shifts as that site shifts with the flows. It is to write despite the unimageable gap between theory writing and the transpacific, to reckon with the unimageability of ‘writing transpacifically’.

What is unimageability for this paper? This paper treats unimageability as a specific condition of unimaginability. Unimaginability might suggest a complete inability to think and wonder, whereas unimageability suggests thinking and wonder can still occur albeit without an ability to tie a specific image to thought. Unimageability thus becomes a commentary on planning’s habit to demand thought produce a picture (plan). It also comments on planning’s common regard of the unimageable, unmappable, and unplannable as missing thought. Unimageability embraces modes of thinking that are not-articulatable textually, verbally, or with images. As this paper suggests later, thinking that generates no fixed image might indirectly force thinking to not rest. It drives at least a desire for openness.

The transpacific is uncontainable as theory’s object. The transpacific permeates the writing-act and the concepts of ‘writing transpacifically’. The more images, words, maps, or diagrams generated to represent the transpacific, the more things are added to intensify the transpacific’s body, the more these images and words highlight what they have missed, thus making the transpacific more unimageable. Furthermore, international planning’s relationship and reliance on global organizations like the United Nations and the International Monetary Fund to implement global change should be checked as these organizations often contribute to inequity (Brenner & Schmid, 2015; Hardt & Negri, 2000; Roy, 2005).

Theory is not broad enough to encapsulate the transpacific’ totality. Theory is never minute enough to describe the intricacies of Vancouver, Hongkong, Riau, or the space between them. Details produce details. Inadequate representation of the transpacific is a condition of writing this paper.

How does one think and write the ‘trans’ in the transpacific?

Theory Yet-to-Come

Theory in medias res

Acknowledging the transpacific future as unimageable is not an absence of hope. Perhaps, theory’s refusal to represent the future hints at a writing practice that reserves a space for hopes of other futures. Refusal sustains hope not as a fixed destination, but a desire to keep inventing. Unimageability is not a step to imageability. These unimageable other futures may still mentally and physically affect us, inciting mind and body. For planning theory to write without imageable futures may mean forgoing planning’s binarized chronology of ‘isms’ where each successive ‘ism’ sees itself as the best future.

Why is forgoing binary helpful? Cultural theorist Homi Bhabha (1994) views theory’s transformative capacity as not through “a mimetic reflection of an a priori political principle” (p. 25) nor flipping the oppressor-oppressed binary. Rather, theory empowers its readers when theory can “overcome the given grounds of oppositions” and “identikit political idealism” (Bhabha, 1994, p. 25). This empowerment is immanently expressed when readers are spurred to read and write other futures, ones that can be post the colonial and post the post-colonial. Writing and reading theory produces:

A place of hybridity, figuratively speaking, where the construction of a political object that is new, neither the one nor the other, properly alienates our political expectations (…) The event of theory becomes the negotiation of contradictory and antagonistic instances that open hybrid sites and objectives of struggle and destroy those negative polarities between knowledge and its objects, and between theory and practical-political reason (Bhabha, 1994, p. 25).

More than compromises between polarities, hybrids and negotiations are chimeras, retaining antagonisms and agonisms. In theoretical-texts, they can be tensions and paradoxes that push representational thinking’s limits. And the term ‘negotiate’ can also mean negation: negating what we or something are currently, not to efface existence, but to shed stale identities.

Bhabha (1994) outlines reasons to change theory’s form, first “the historical moment of political action must be thought of as part of the history of the form of its writing” (p. 23). Texts are not just vessels to record historical-political actions; they occupy the same site and time as actions. Second, given the concurrency of texts and actions, it is to “rethink the logics of causality and determinacy” (Bhabha, 1994, p. 23) of theory-writing. A text is neither anterior to (or a cause of) nor an afterthought (determined by) of political actions. A theoretical text is an object evolving with a site’s political actions. A site changes how readers read the text and the text’s meaning. A reader’s style of reading can change a text’s meaning and even the site, insofar as the text is part of the site. A text can change a reader’s style of reading and how they experience the site. Reader/writer, site, and text are situated through each other. If reader/writer, site, and text are situated through each other, one might suggest, theory do not just map changing terrains; maps add to changing terrains. And theory writing’s contiguity with site makes it always in what Bhabha (1994) calls a “process of emergence” (p. 22) in media res (middle of things)

Bhabha’s idea of theory-writing becoming more transformative if it exceeds representation of the ideal world can be further explored through philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s (1994) idea that writing style and composition are crucial to stir corporeal-mental changes in readers. The ‘transformative’ lies in how these changes, though uncategorizable by established sociopsychological concepts, can still produce desires other than capital’s desires. To stir changes:

The writer uses words, but by creating a syntax that makes them pass into sensation that makes the standard language stammer, tremble, cry, or even sing: this is the style, the “tone”, the language of sensations, or the foreign language within language that summons forth a people to come. (Deleuze & Guattari’s, 1994, p. 176)

A text’s transformative power is “the vibrations, clinches, and openings” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1994, p. 177) that it spurs in readers to explore new common actions with each other, opening to a people to come. Philologist Anne Fleig (2019) notes, texts have “bodily dimensions” (p. 180) that impress on the body and mind. Brain synapses dart as typing fingers quiver. The transformative event is when an affected reader’s body-mind rethinks and rewrites texts (e.g., this paper) to create new openings.

Perhaps, ‘writing transpacifically’ takes place in the middle. For this paper, this includes being in that space between the corporeality of dog-eared philosophy books, the queasiness from watching jungles burnt for palm-oil fields, or transpacific capital condos, etc. Inklings of thought appear in this in-between space. Being in the middle of things is why this paper is still being written.

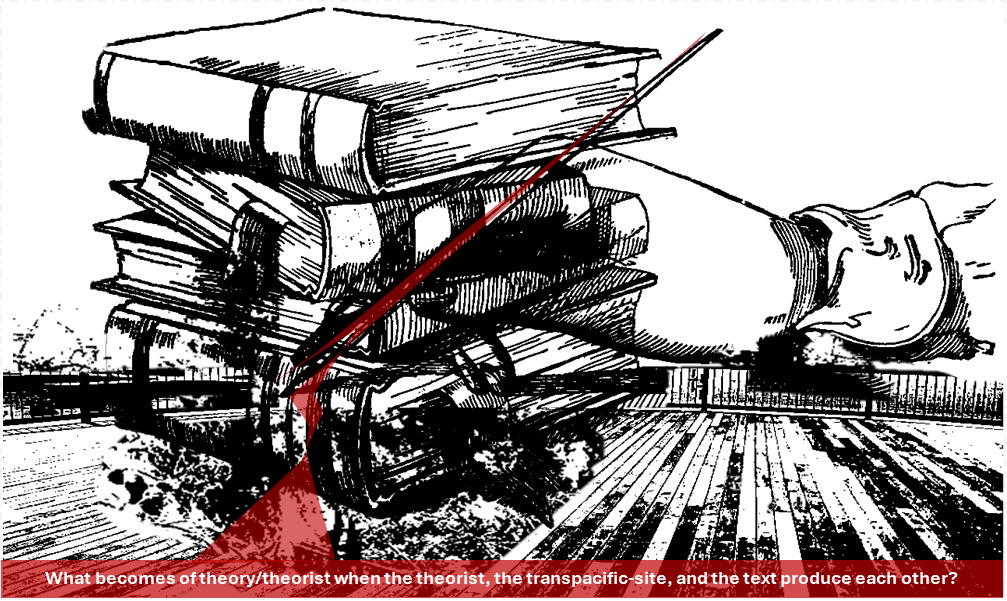

Dirtying a theoretical-text

This paper’s words, concepts, references, images can be deliberately (mise)used by readers, writers, artists, designers, and other sojourners traversing in (and traversed by) transpacific flows. Readers can take concepts from this paper and use them in ways useful to their geography, mode of resistance, and even corporeal-mental make-up. Even how this paper’s concepts are felt (recalling how texts have bodily dimensions) differs according to a reader’s particularities.

Different usages can change a text’s theoretical core, its interiority. Philosopher Hélène Frichot (2019) calls these different usages of theoretical-texts as ‘dirtying’ theory, but dirtying realizes a text’s transformative powers:

Theories are good for nothing unless they are bound up with the muck of mundane relations on the ground, with the kind of environmental things that are increasingly at stake today, that were at stake yesterday, too, and that certainly will be at stake tomorrow. Make a mud map, find your way through the dirt. (Frichot, 2019, p. 11)

Dirtying theory does not weaken theory but liberates it from a long-held belief that theory must provide models or solutions for practitioners. This opens theory’s relation to practice.

Texts as tools for excess

A theoretical-text is an object situated between a theorist/writer and their readers. Jane Rendell (2010) suggested being aware of a texts’ spatiotemporal condition can change how theory writing is approached and written. As such:

A shift in preposition allows a different dynamic of power to be articulated, where, for example, the terms of domination and subjugation indicated by ‘over’ and ‘under’ can be replaced by the equivalence suggested by ‘to’ and ‘with’. (Rendell, 2010, p. 7)

Rendell’s idea of theory writing ‘with’ suggests theory need not precede actions. In planning, this means theory need not define or regulate practice’s procedures or parameters: an asymmetry between theory and practice. Theoretical-texts can be treated as tools. And Michel Foucault (1977) noted tools are not moulds; they have multiple functions with multiple outcomes. Crafts persons invent new uses for the tools, even modify them. To make a theoretical-text a tool is to rethink theory’s usual compositional, methodological and epistemological expectations, and here words are not just references. But as design theorists Ellen Lupton and Abbot Miller (1999) suggested, the page itself can “critically engage the mechanisms of representation” (p. 23). Writing could “generate a trail of argument in excess of the seemingly self-contained body of the work. The organs of the text are sites for elaboration, expansion, overflow” (Lupton & Miller, 1999, p. 50).

Could excesses and overflows be the elements that refuse to let die the thinking, writing and inventing of yet-to-come people and places across the Pacific? Could refusing to say what life must be, and let things overflow, preserve life? As Deleuze and Guattari (1994) noted, life prescribed in advance is a still-life, indifferent to living. Instead prescribing life, maybe writing could be:

A sort of groping experimentation, and its layout resorts to measures that are not very respectable, rational, or reasonable. These measures belong to the order of dreams, of pathological processes, esoteric experiences, drunkenness, and excess (. …) One does not think without becoming something else. (Deleuze & Guattari, 1994, p. 42)

Could text be tools for reader and writer to experiment on becoming something else?

Writing concepts without interiority

If a text is a tool to be used, how that text is composed matters. Flexibility and ambiguity could be built into the textual composition. Instead of saying “Concept A is X,” explore ways to write “Concept A is A1,2,3….” The “…” is more than Concept A. A concept is differing from itself, even within the same essay. Undoing a concept’s supposed interiority or proper meaning.

Concepts without an interiority or proper meaning can sound frightful, even silly. But concepts without interiorities, or de-interiorised, are not voids. Here, a quick elaboration of how this paper understands ‘interiority’ might be helpful. This paper’s term ‘de-interiorization" draws parallel to Deleuze and Guattari’s (2005) term “de-territorialisation,” which is undoing a territory’ stability. De-territorialisation occurs when colonial structures destroy land and communities. However, de-territorialisation can also be undoing constraints, like when colonial structures are dismantled to liberate people, place, communities, thinking. Furthermore, de-territorialising colonial structures is simultaneously a re-territorialising spaces into ones with new relations of care and ethics (2005).

Drawing from Deleuze and Guattari’s pairing of de- and re-territorialization, this paper understands de-interiorization as undoing constraints, accompanied by re-interiorization. Hence, words and images that make up a concept can be reshaped in ways to liberate even the concept itself. Re-interiorization also occurs when readers fold in their own words and images to hybridize them with words and images they encounter in a text (like this paper). Re- and re-interiorization of concepts involves readers. Through readers’ critical reading and use of a concept, a seemingly unified concept develops a malleable porous interiority that is in exchange with its exterior. In this exchange, a concept is a territory which contours and core shift with each new connection; its form is “that which is not yet” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1994, p. 101). These shifts unsettle the mechanisms of representation, deferring what the concept must say, “A concept is not paradigmatic but syntagmatic; not projective but connective; not hierarchical but linking” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1994, p. 91).

Creating new concepts, even ones without interiorities or fixed meanings, also happens via what this paper calls ‘aesthetical’ connections. For this paper, the term ‘aesthetic’ refers to not just an idea of pleasing (or lack of). It also relates to changes in our sensate faculties’ capacities. For example, imagine the connections between words, sounds of words, graphicality of words, images, even blank-spaces on a page (like in this paper). Such connections do not always yield ‘proper’ articulatable concepts. Nonetheless, this meeting of words, sounds and images can still transform readers in corporeal and para-philosophical ways. These are aesthetical-sensate transformations. Here, aesthetics pertains to developing new perceptions and sensations, which, in turn, may spur new modes of living with self and others. Some new modes of living with others include new relations of care; hence the aesthetical also expresses an ethical dimension. Furthermore, readers can bring their own words, sounds, and images and connect those to the ones they encounter in a text. Readers can also expand these aesthetical connections. Even misreading a concept (in this paper) can proliferate connections.

Disjointed words, sounds and images are still useful to the process of forming new lines of thought. How? Deleuze and Guattari noted, disjunctions between things—not synthesising into a proper concept or image—can rouse a body-mind to scramble to forge even uncommon uncomfortable connections, hoping these connections may birth new concepts and new ways to articulate these new concepts. This scrambling to forge can be an experimental endeavour. As Deleuze and Guattari (1994) asked “What would thinking be if it did not constantly confront chaos?” (p. 208).

What is thinking and writing becoming when confronting the chaos of conceptualising ‘writing transpacifically’? The word ‘writing’ has its own conceptual interiority; it has an image of someone typing or holding a pen. The word ‘transpacifically’ suggests objects or events that stride the pacific. Yet no clear image appears when ‘writing’ and ‘transpacifically’ meet. Where is the geography of ‘writing transpacifically’? This paper was typed in Vancouver, Hongkong, and Singapore, but can my fingers type across the pacific? Does ‘writing transpacifically’ mean physically inhabiting all pacific cities? Is ‘writing transpacifically’ the unimageable space between cities? Can juxtaposing ‘writing’ with ‘transpacifically’ create an aesthetical connection? Evermore questions can be posed, when asking “what is thinking and writing becoming when confronting the chaotic task of conceptualizing ‘writing transpacifically’?” As you read these words about ‘writing transpacifically’, are you adding words and images to it, creating new aesthetical connections with it, de- and re-interiorising it?

Estranging Language for the Yet-to-Come

By now, you might notice this paper is trying to articulate a concept of ‘writing transpacifically’ with words, collages, quotes from Bhabha, Deleuze and Guattari, etc. But this concept has not yet solidified. But this ‘yet’ has a curious temporality; it is not something to be known eventually. This ‘yet’ has other ‘yets’. These other yets can be felt corporeally and mentally, sometimes intensely, without being imaged. These yets can be people-yet-come, even theories-yet-to-come.

By remaining yet-imageable, the concept of ‘writing transpacifically’ eludes even this paper’s gaze. This elusion immanently expresses the yet-imageable gap between theory and the transpacific. But this gap can still be politically potent. This gap between theory and the transpacific, expressed through the yet-imageable concept of ‘writing transpacifically’, is a sort of defence against imperial economics’ appropriation of any well-intentioned visions of Pax Pacifica into marketable entities. Note: The terms yet-imageable or unimageable in this paper are not ‘never’. Something can actualise, but this to-be-actualised thing, future, concept, relation, people, cannot be planned or described. The actualisation process holds yet-imageable potentials. Maybe the yet-imageable gap between theory and the transpacific is a way for theory to say ‘No’ to imperial geography-making.

For the above reasons, this paper intentionally does not present any futures. Its words and images are materials for readers to experiment on how else to live in, to contend with, to reorient, to resist and even embrace extractive transpacific flows: for readers to write their own concepts of ‘writing transpacifically’, including ones that are yet-imageable.

To express this sense of a yet-to-come, planning theory’s language and style might have to veer from its usual telic voice. Veering away is not simply a return to a ‘native’ minority tongue. Rather, it is to twist language to go beyond the usual minority-majority binaries in our acculturated sociopolitical, economic, historical, and cultural imaginations. Discussing Kafka’s unsettling of linguistic-cultural stereotypes and binaries, Deleuze and Guattari (1986) suggested, even when writing as a demographic minority, language becomes transformative when minority-ness becomes something that dominant sociocultural, economic, linguistic, and spatial systems cannot easily appropriate or categorise. This minority is not the majority’s opposite. It is never a ‘proper’ minority. It estranges its own tongue to avoid capture, hence retaining its capacities to invent new modes of living.

Estranging one’s tongue in planning’s context might be to develop ways where planners and theorists (especially demographic ‘minority’ ones) can unsettle planning’s linguistic norms that often rely on binaries between minority and majoritarian spaces and epochs? Recall Bhabha’s point on how anti-imperialist struggles’ transformative capacity is not through identikit sociopolitical idealism. So, estranging planning’s language is more than cancelling majoritarian planning terminologies, and replacing that with ideal demographic minority words. Instead, “How to tear a minor literature away from its own language, allowing it to challenge the language?” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1986, p. 19).

Refusing an ideal minority future is a caution against majoritarian planning’s ability to appropriate minority-ness into land-use projects that might fuel ethno-spatial schisms. Here, estrangement alters planning’s epistemology and historiography, and its conception of space. For planning theory, it is to produce texts that cannot be easily translated into ‘plans’. For instance, can common spatial words like ‘interior’ become yet-spatializable, refusing the term ‘interior’s’ usual genius loci association? What is it to write against the academy’s involvement in imperial desires?

A theorist’s ‘I’?

How planning forms its ‘I’

To appear scientific, planning often equates thinking with an unchanging rational ‘I’ that reigns over the sensate faculties. In conventional western science and even metaphysics, sensate faculties’ existence is seen as dependent on the ‘I’. (I think, therefore I am). The privileged ‘I’ is secured by an assumption that planning’s canon of rational unbiased models represents this 'I’s unbiased mind. Furthermore, planning theorist Jean Hillier (2008) noted, planning often only equate representable or imageable things like models as thinkable. The unrepresentable, unplannable is unthinkable. Hillier elaborates:

The idea that knowledge is re/presented and thus determined by the representational powers of the subject is an essentially Kantian view in which representation is a threshold that limits thought. Something cannot be thought if we cannot describe it or represent it. Something cannot be understood if it is not explained or represented. (Hillier, 2008, p. 25)

Hillier’s observation on how planning assumes only the representable is thinkable also reveals how a circular logic is used to affirm a planner’s ‘I’: The ‘I’ is thinkable as it is representable by models. But it is only representable because it is thinkable. In this hermetic circularity, the representable rational model become the thinkable rational ‘I’, vice versa. However, Hillier (2003) notes this circularity hides biases. When planners “prefer some values to the relative repression and exclusion of others” (Hillier, 2003, p. 41), certain economic, political and historical processes are privileged. Similarly, what is privileged in the process that builds a planner or theorist’s thinkable and representable ‘I’?

Planners know a plan is not the terrain; we are never outside of it. We even know the biases that built our ‘I’. Yet, the planning milieu (the office, social networks, etc.) socialises us to trust models. However, this trust in models is often not coerced. Economist Frédéric Lordon (2014) noted, there are things and processes we naturalize as part of our own selfhood formation, even if this reduces our capacities to act and think critically overall. Models are one of these things. We naturalize models as formative for our ‘I’ because they represent us. Models offer glimpses of the good future. And we are socialised to see this future as if our ‘I’ remains unchanged in that future. The identicality between the model and the future is comforting; identicality is a bulwark that protects our ‘I’ from the terror of the terrain and time.

Identicality is so important for planning that ‘difference’ is designed as a specific ‘difference’. In plan-speak, differences are options. Options are a model’s controlled-variations that do not disrupt the model. Options retain an identicality to the model. For example, options presented in social housing plans rarely disrupt existing transpacific real estate finances, bank interests, or the imperial logic of reterritorializing land. Here, planned differences represent the models, hence our ‘I’.

Socialised to trust planned differences, when we encounter a person, space, event, or things that cannot be represented by planned differences, we treat them as unthinkable. Unthinkable things are seen to not add to the ‘I’s’ formation. They are outside of planning’s ‘good’ canon, even cast as bad. Moreover, we imagine becoming ‘good’ planners if we successfully represent or think of what we encounter through the canon’s models, protocols, and procedures. The process of making things representable and thinkable, thus ‘good’, also produces our good ‘I’.

Questions beget questions… begets ethics

Critiquing planning models is not forgoing ethics. To critique is more than judging whether something ‘measures up’. To critique can be to ask questions, even ones that planning is unaccustomed to, such as questions that cannot be solved by codes and plans. For example, a question like: How to design pacific-scale housing plans outside imperial geography? Notwithstanding the transpacific’s unscalability, there is no one way to counter imperialism. Imperialism and capitalism even designed themselves as unescapable (Fisher, 2009). Nonetheless, such questions’ unanswerability can rouse mental and sensate faculties. This, in turn, spur us to craft new relations of care with others to explore ways of living outside codes or plans. This unanswerability spur questions that beget other questions.

When asking questions that beget questions, questions about the questioner’s ‘I’s’ positionality may surface. These questions may shift the ‘I’s’ relation with others, which leads to another sets of questions appearing, extending the questions. As such, questions that beget questions is an event that constantly adjusts the relations of care between different ‘Is’, transforming each ‘I’. Adjusting ways to care for and with others can be said to express an ethics. Citing Spinoza, Gilles Deleuze (1988) noted ethics is an act of deciphering which relations to build to increase each other’s capacities to act and think critically, without being reduced to a single identity. One desires not just for oneself to be able to transform, but for others too (Spinoza, 1996, Book 4, Proposition 37. Alternative Demonstration). Perhaps, it is theory-writing being connected to forming new relations that makes it an ethical pursuit.

Understanding difference as differing from itself

To further explore a planning’s ‘I’, one could query the nature of thinking and the nature of difference. Deleuze’s (1994) writings can be helpful here; he observed how difference is commonly (mis)understood, when conceived through fixed identities and binaries. Hence, “Difference becomes an object of representation always in relation to a conceived identity, a judged analogy, an imagine opposition or perceived similitude” (Deleuze, 1994, p. 138).

Deleuze then noted, difference is assumed to be a value bestowed by the logic of a static ‘I think’ (and its variants like I conceive, I judge, I imagine, I remember, etc.). Furthermore, this ‘I’ assumes anything it encounters is also static. Neither the thing (valued as different by the ‘I’) nor the ‘I’ transforms or affects the other in the encounter. Each is already-imbued with a fixed identity. By assuming fixed identities, the ‘I’ encounters the world through what Deleuze (1994) calls a “model of recognition” (p. 138). In this model, thinking’s validity is based on how closely the ‘I’ can put people, communities, events, or places into various established identities. ‘Difference is crucified’ here.

Deleuze (1994) asked, could “difference in itself” (p. 55) be affirmed and experienced, instead of difference based on similitude and binary? Difference in itself is a difference that takes shape when something is differing from itself in a state of in-between. It is non-representational, non-recognitional, non-identitarian. In differing from itself:

The object must therefore be in no way identical [to itself] but torn asunder in a difference in which the identity of the object as seen by a seeing subject vanishes (. …) Divergence and decentering must be affirmed in the series [of differentiations] itself (…) Difference must be shown differing. (Deleuze, 1994, p. 56).

One might say the interiority of that which is differing from itself is always in exchange with the exterior. Its interiority is a movement, a differentiation. Differing from itself, it does not avail itself as a static object for planning’s ‘I’ to gaze at. Now, is the transpacific, and the countless things that constitute it, not differing from themselves? If so, what becomes of planning and the theorist’s gaze or ‘I’, or their thinking process, when caught amidst an ever-differing transpacific? As we try to image the ever-differing transpacific, how is planning’s ‘I’ differing from itself?

What wills thinking in the transpacific?

If the ‘I’ is differing from itself alongside the transpacific, who wills thinking? The theorist? The transpacific? Is a theorist not a constitutive part of the transpacific, given they form a mental-corporeal continuum with the transpacific’s many constitutive bodies and concepts? Could the will to think emerge from this imageless but palpable continuum?

A theorist’s body-mind and the transpacific’s many constitutive bodies-minds have forces that circulate through and affect each other. A theorist’s thoughts can be said to be partly affected and roused by these other bodies-minds. Vice versa. For instance, when encountering the media showing Asian migrants vilified for rising housing prices, I (this paper’s writer) became too physically and mentally stunned to assign meaning to this interconnected terror. In this stunned state, my muscles tensed, roused yet-imageable words, images, and sounds to flicker in my mind’s eye. This paper’s yet-imageable words, images and sounds are not willed by me alone. Yet-imageable words, images, and sound are the inkling of thoughts rising in the continuum between us and the transpacific’s constitutive matters. Philosopher Gregg Lambert (2002) notes, thinking is most apparent when “life is implicated with matter” (p. 41). Transpacific flows will our will to think.

If thinking is willed and produced in the mental-corporeal continuum a body-mind has with the world, then the ‘I think, therefore I am’ logic falters. The ‘I’ is neither the genesis of thought nor controller of the body. Instead, thought takes place between one’s mental and sensate faculties, as well as the continuum one’s mental and sensate faculties has with the world. It is for this reason that Deleuze (1994) read the word “Sense” (p. 139) (‘Sens’ is ‘Meaning’ in French) from the phrase ‘making sense’ to include the sensate faculties ‘sensing’ the world. What is sensing? Sensing suggests a body-mind middling through the conflux of sounds, bodily gestures, words, or images, while interacting with other humans and non-humans, however briefly or minutely. It is less recognising the world through established meanings, or insisting a person, thing, place, or concept’s interiority is innate and fully representable. In middling through even unfamiliar bodily gestures and states, or interacting with the world, new perceptions and sensations form; from here new ways of conceptualising or articulating these perceptions and sensations also form (Smith, 2022). Sensing is cultivating new modes of living.

It is this understanding of sense/sensing as cultivating new modes of living that led Deleuze (1994) to say, “It is not a sensible being but the being of the sensible” (p. 140). In this phrase, the first ‘sensible’ is a conventional rational ‘sensible being’ whose thought process is limited to recognising commonsensical proper concepts. In contrast, the second ‘sensible’ suggests sense precedes the ‘I’ or being – being is formed by their sensate (and mental) faculties’ continuum with the material sensual world. While thoughts emerging from this continuum can only be sensed, nevertheless they can loop back to transform the physical brain, body, and mind, to generate other thoughts that may also only be sensed. In a way, thoughts that can only be sensed beget more thoughts that can only be sensed. For Deleuze (1994), thoughts that can only be sensed and remain unrecognisable as proper concepts are still powerful because they create “sensory distortions” that “awake memory and force thoughts” (p. 237). Thinking cease to be perfect recollections but become the mental-synaptic-visual-corporeal forces that keep stirring new sensations in us, and simultaneously spurs our flesh-brain to will thinking.

Thoughts that can only be sensed may not help a theorist spatially or conceptually locate their ‘I’ in a precise spot in the transpacific. However, this impreciseness is not an emptiness to be filled, but a force that can cultivate desires to invent evolving ways to map, write, and connect to articulate new solidarities, hopes, and relations of care with other transpacific sojourners. One might say, this imprecision enriches the transpacific, maybe even the process of being ethical. Perhaps, the question ‘who wills thinking in the transpacific?’ is one only answerable by something that can only be sensed.

We are (in) the site

‘Writing transpacifically’ occurs in-situ and ex-situ. One always writes in a grounded site and is affected by that site’s forces. But these forces are connected to forces exterior to the site. A theorist (subject) may write reflectively about the transpacific (site/ object) in a text (another object.) But both theorist and text are also in, and modulated by, a specific transpacific site and its in- and ex-situ forces. In fact, both theorist and their text’s capacity to reflect on the site and its forces are, at least partly, conditioned by the site and its forces. A theorist is not a dispassionate body standing afar. A text is part of the transpacific’s material reality. ‘Writing transpacifically’ attends to how the trans of the transpacific loosens the subject-object-site hierarchy. We are (in) the site.

Architecture theorist Jane Rendell’s (2010) concept of “site-writing” (p. 18) can help further query this subject-object-site hierarchy. Rendell (2010) suggests, the writing-act taking place in a site can “develop alternative understandings of subjectivity and positionality” (p. 18) to unseat the theorist-author subject, blurring interiority and exteriority. Rendell’s idea can be extended to ask, what ex- and in-situ forces constitute our theory-writing desires? Did we desire to theorise the transpacific, or did it move us to do that? Site compels us. A site compelling us suggests thinking takes place in and transforms with a site’s constitutive objects and materials. Geographer Nigel Thrift (2008) highlights thinking’s materiality, “Not only do objects make thought do-able but they also very often make thought possible” (p. 60).

Design theorist Suzie Attiwill (2016) likewise noted, theorizing is not just a mental exercise of identifying known things or phenomena. Instead, one approaches the “generation of knowledge as a material thinking” (Attiwill, 2016, p. 201). Extending Attiwill’s notion that theorizing is material, one might suggest, theory-writing includes cultivating new modes of living and thinking through the (writer’s) body and material world. For this paper, it is cultivating new ways to live, move, think, and write in the transpacific’ expanded site; factor the feelings emerging at a convergence of fingers, keyboard, eyes stung by news of burning palm-oil fields, philosophy books’ dog-eared pages, the brain’s anxious synapses, etc. An urgent feeling in our fingers poised to type can be inklings of new places, people, solidarities, and hopes.

As you read this paper, what becomes of this paper’s body and its site? Has your own in-situ and ex-situ forces from our own grounded site changed this paper, or changed ‘writing transpacifically’? What becomes the unimageable gap between this paper and your mode of thinking transpacifically?

Pacifica Incognita

Things that constitute a theorist’s ‘I’ in the transpacific may be non-recognisable, but this does not mean the ‘I’ is a void. The ‘non’ in ‘non-recognisable’ is not a lack to be filled or defined by proper concepts. Like how the ‘non’ in ‘non-binary’, which presence is not the opposite of ‘binary’, the non-recognisable has a presence which always affords new ways to relate to it, to change, and be changed by it. The non-recognisable can be pre- and extra-linguistic; again, something that is only sensed. Its presence is one that opens onto more potentials. However, opening to more potentials is not a discovery of existing territories and concepts, or improving old ones. Rather, it is creating territories and concepts, even creating things that can only be sensed. It is a newness that, as Deleuze described:

should not be understood in a historically relative manner, as though the established values were new in their time and the new values simply needed time to become established (…) The new, with its power of beginning and beginning again, remains forever new (. …) The new – in other words, difference – calls forth forces in thought which are not the forces of recognition (…) [but] from an unrecognised and unrecognisable terra incognita. (Deleuze, 1994, p. 136).

The non-recognisable is a newness that is always out of joint with being recognisable, even with itself. It is differing from itself: A1,2,3,4,5… It pushes continually against imageability. And this continual push against imageability can even make theorists writing about it lose their self-position. Its movements envelop even a theorist, making it hard for a theorist to step aside to objectively describe this newness’ form. A theorist loses the ability to gaze at the non-recognisable, and this unsettles a theorist’s eye and ‘I’. It challenges a theorist’s epistemological ground. A theorist is in, and part of, a terra incognita.

What might be planning’s terra incognita? To address this question, one can first look at planning’s desire for ‘terra cognita’, often manifested in its list of models. This list can be inexhaustibly long, but countably infinite, insofar as each model is representable by a proper concept. This list of representable models constitutes a sort of ‘terra cognita’. However, what happens when each model is shown to be deformable and reformable into something else. For instance, the ‘surplus-supply equals housing affordability’ adage falters, when it is complicated with various concepts of transpacific geography, ethics, migration, economics, etc. The ‘surplus-supply’ model can be dissected, mixed with other concepts, and reassembled into other lines of thoughts, even thoughts that can only be sensed. Here, planning’s list of models can harbour a newness that lies in their potentials’ potentials. And because potentials’ potentials are often something that can only be sensed, and because sense is undividable into discrete quantifiable objects and concepts, this list of models come to express an uncountable infinity. This uncountable infinite resists a theorist’s gaze. To image this list is not solvable by applying the correct quantification or qualification methods. Contending with this list’s uncountable infinity produces an in-cognisable territory. How to map the list’s potentials’ potentials?

A terra incognita is topographically unmappable. But it can be sensed: most acutely when cartographic methods fail, most palpable when neither theory nor theorist can pinpoint their exact location within, or in relation to, the terra incognita. There is no terra firma grounding a theorist’s conventional subject-object relations. As more words are typed or maps charted (as in this paper) to image the terra incognita, its inexhaustibility intensifies. Writing expands the theorist’s ever-incompletable ‘I’.

Postlude: This Paper’s Useful(ess)ness?

At this point, one could ask, is this paper useful for the Pacific’s liberation? This question also interrogates planning’s understanding of ‘usefulness’. This paper would be useless if usefulness denotes a utilitarian function (e.g., Readily applicable for practitioners to use to produce quantifiable futures). However, what if a text’s usefulness is a refusal to cede thinking over to an image of a masterplanned Pacific? Could a refusing imageability be refusing to terminate thinking? A refusal to stop thinking of yet-to-come people and lands, yet-to-come transpacific theories? Useful uselessness?

Uselessness is a funny thing. The inability to make Pax Pacifica a terra cognita may be why we continue to bear desires (yes, anxious ones) to build even more yet-imageable transpacific solidarities in hopes to counter imperial geographies, racism, palm-oil driven displacements, transborder smogs, housing unaffordability, etc. We do not know what these solidarities will actualize as, but we write on as the production of texts, media and connections is what sustains life (Flieg, 2019). It sustains life through connections of care. Texts (like this paper) are just tools to build those connections.

To this paper’s readers: Please do not take this paper as a key to solve transpacific woes. In fact, the act of writing this paper shows its limits. It cannot spatiotemporally step outside the transpacific to foresee an end-all solution. All it does is offer certain textual, conceptual forces to readers. It does this despite never knowing how its forces may augment it readers’ own resistances to an imperialised transpacific. These forces’ transformative capacities emerge when readers use them. In the time of reading this paper, you can restart and re-end it in many ways. This is why this paper is still being written.