Introduction

The On Lung Ching Chiu 安龍清醮 (Ritual of Settling Down the Dragon for Purification) is a septennial festival held in Kau Lau Wan Village, Sai Kung, Hong Kong. Kau Lau Wan remains a rural settlement accessible only by waterborne transport, effectively rendering it akin to an isolated island. Kau Lau Wan’s boat people villagers practiced On Lung Ching Chiu ritual as an act of prayer and veneration, with Tianhou 天后 (Empress of Heaven) as the primary deity honored. Tianhou (also known as Mazu 媽祖) is one of the most prominent Chinese deities, particularly revered among maritime communities. As Grydehøj (2024) notes, she embodies multiple aspects: the human figure of Lin Mo who lived on Meizhou Island, a tutelary deity protecting fishers and sailors, and the celestial Tianhou recognized by imperial courts. This multifaceted nature allows her to serve as both a domestic goddess and a sea goddess, making her particularly significant for fishing communities and coastal peoples whose sense of home and place has traditionally been precarious. Within the context of seeking both mainstream social legitimacy and maritime divine protection, the Kau Lau Wan community positioned Tianhou as the festival’s principal deity, along with other deities associated with the local community—such as Shuixian Yeye 水仙爺爺 (the Water Immortal), Tudigong 土地公 (the Earth God), and Yuncai Tongzi 運財童子 (the Wealth Child)—as well as Tianhou deities from neighboring regions (e.g., Sai Kung 西貢, Leung Shuen Wan 糧船灣, and Tap Mun 塔門) who are invited to the ritual pavilion for public worship and veneration. To comprehensively explore this festival, I conducted interviews with the village head and senior villagers and carried out three year-long field investigation between 2021 and 2023 as well as the two full-day observation of the rituals in May 2023.

The On Lung Ching Chiu is distinguished from other Ching Chiu rituals in Hong Kong by its specific focus on ‘settling down the dragon’ 安龍, traditionally associated with Hakka communities’ concerns for land fertility and territorial blessing. While sharing common elements with the more widespread Tai Ping Ching Chiu 太平清醮 festivals, such as deity worship and community purification, the On Lung ritual traditionally emphasized the relationship between human settlements and the dragon veins (龍脈) believed to course through the landscape. This distinctive characteristic makes the ritual’s adaptation by a maritime-oriented community particularly significant for understanding processes of cultural transformation.

This study specifically examines how the boat people of Kau Lau Wan have actively engaged in reconstructing their cultural boundaries through religious rituals. By analyzing the ways in which they have adapted the On Lung Ching Chiu festival—a ritual originally rooted in Hakka traditions—the research sheds light on the processes of cultural negotiation and identity formation within marginalized communities. The focus is on understanding how the boat people assert their agency in redefining cultural narratives, thereby challenging conventional perceptions of subaltern groups as passive recipients of dominant cultural influences.

Ethnicity and heritage

It is essential to clearly define the key ethnic and cultural identities discussed in this paper. The term Hakka 客家 refers to both an ethnic group and speakers of the Hakka dialect who historically migrated from northern China to the south, establishing settlements throughout the Pearl River Delta region. In contrast, ‘boat people’ (水上人), also known as Tanka 蜑家 or Dan 蛋 in different historical contexts, traditionally lived on boats along the South China coast. This distinction is particularly evident in the local geography, where the village near Kau Lau Wan was historically known as Tan Ka Wan 蛋家灣, explicitly referencing its boat people or Tanka residents. While scholars have often treated boat people as an ethnic category, it more accurately describes a socioeconomic and cultural identity shaped by maritime lifeways and traditions (Lin & Su, 2024). The case of Kau Lau Wan presents a valuable example of how these two groups historically coexisted and interacted, creating a complex community dynamic that challenges simple ethnic or cultural categorizations. This coexistence and interaction between Hakka and boat people communities ultimately shaped the village’s distinct cultural landscape and religious practices, as evidenced by the evolution of the On Lung Ching Chiu festival.

The timing of this research during the COVID-19 pandemic (2021-2023) provided a unique opportunity to observe how the community adapted and maintained its cultural practices under extraordinary circumstances. The festival’s postponement from 2022 to 2023 due to social distancing restrictions, and the subsequent determination of overseas villagers to return once restrictions were lifted, highlighted the ritual’s crucial role in maintaining transnational community bonds. The pandemic context revealed additional layers of significance in the On Lung Ching Chiu’s function as a mechanism for cultural preservation and identity maintenance across geographical boundaries. Despite the challenges posed by global health restrictions, the community’s commitment to maintaining the ritual—even with necessary adaptations—demonstrated the festival’s enduring importance in articulating and reinforcing community identity. These observations during the pandemic period add valuable insights into how marginalized communities utilize religious practices to maintain cultural cohesion even when faced with unprecedented external constraints.

The complex interplay between Hakka and boat people traditions in the On Lung Ching Chiu makes it an important case study for understanding cultural heritage preservation and transformation. Although Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) may seem to encompass the long-standing cultural traditions of communities, it is a relatively new concept in the cultural industry and academia. In 2003, UNESCO recognized that the World Heritage Convention, which had been in operation for years, had overlooked cultural traditions not associated with historic sites or artifacts, particularly festivals and rituals lacking appropriate frameworks for sustainable transmission and safeguarding. This realization prompted the adoption of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2003, which subsequently came into effect in 2006 (Smith, 2006, p. 106–113).

Since then, signatory countries have developed national ICH inventories and undertaken related revitalization and preservation efforts according to their internal needs. The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region also began this work in 2006 by establishing an Intangible Cultural Heritage Unit under the Hong Kong Heritage Museum, which was later upgraded to the Intangible Cultural Heritage Office in 2015 (Zou & Chau, 2011). In 2009, Hong Kong was invited by the State Council of the People’s Republic of China to submit nominations for national-level ICH items, leading to the release of Hong Kong’s first ICH inventory containing 480 items in 2014 (Liao & Liu, 2014, p. 203), and the subsequent designation of the first 20 representative ICH elements in 2017. Furthermore, in late 2018, the Hong Kong government allocated HK$300 million to implement the ICH Funding Scheme, which includes inviting experts and scholars to investigate various unregistered ICH elements or engaging ICH practitioners to design suitable promotion and education events (HKSAR, 2019).

In the context of anthropological research in Hong Kong, Kau Lau Wan is not an unfamiliar field site for researchers. As early as the 1980s, when the Department of Anthropology at the Chinese University of Hong Kong was established (Bosco, 2017), a research project on Kau Lau Wan was initiated under the guidance and support of B.E. Ward (1919–1983) and Cai Zhixiang (Liao & Liu, 2014). This project involved a group of anthropology students conducting over a year of long-term field investigations and observations in the village. Unfortunately, much of the data and information from this 1980s research project has since been lost (Cai, 2000). As a result, there is a lack of detailed, first-hand understanding of the social structure and related circumstances in Kau Lau Wan during that period. This gap in the ethnographic record poses a challenge for scholars seeking to comprehensively study the village and its cultural traditions over time.

Following World War II, Hong Kong became a major hub for sociologists and anthropologists seeking to understand Chinese society (Baker, 2007; Li R., 2018). This led to the emergence of academic schools of thought such as the ‘South China School’ and ‘Historical Anthropology’, with scholars based in Hong Kong adeptly combining archival research and ethnographic fieldwork to observe the complex and overlapping cultural meanings between the state and local communities (Cheng et al., 2001). This current research attempts to move beyond conventional frameworks that focus solely on the state-local dynamic. Instead, it seeks to explore how grassroots populations utilize religious practices to establish and affirm their worldviews and cultural identities.

Literature Review

While various anthropologists have studied boat people in Hong Kong (Baker, 2007), B.E. Ward’s work was a seminal contribution that profoundly influenced anthropological and sociological traditions in South China studies. In her ethnographic study of the boat people in Kau Sai Chau, Ward identified three distinct cognitive models employed by this community: (1) models of everyday life and current circumstances; (2) ideological models reflecting traditional gentry-based social order conceptions; and (3) observer models, representing surrounding groups’ perspectives, such as farmers and merchants, on the boat people’s way of life. However, as Liu Yonghua (2009) noted, Ward may have underestimated the interrelationships between the current models and observer models. When transitioning to land-based living or adapting to contemporary conditions, the boat people did not necessarily adhere to ideological models but centered adaptations around surrounding populations’ perspectives. The On Lung Ching Chiu festival in Kau Lau Wan can be seen as evidence of this process, where the boat people’s religious practices referenced those of the Hakka people, thereby influencing cognitive models within their community.

Research specifically examining the religious practices of South China’s boat people is limited, but Anderson (1970) provides important contextual background. Anderson critically reviewed theories about the origins of these maritime communities, evaluating proposed roots ranging from descent from aboriginal Yue tribes to refugees fleeing dynastic wars and unrest. He argued that, rather than a single origin, the boat people culture likely emerged through a continual economic and ecological adaptation process, with people from various backgrounds taking up life on the water over centuries. Anderson highlighted the boat people’s cultural integration with surrounding Cantonese populations, adopting similar dialects and maintaining exchange despite perceived ethnic distinctions by land residents.

The fluid nature of identity between Hakka and boat people requires careful consideration. While Anderson suggests the boat people emerged from various backgrounds adopting maritime lifestyles, the specific case of Kau Lau Wan presents a more complex picture. Historical records and oral histories indicate that some Hakka families did transition to fishing livelihoods when agriculture became less viable. However, this occupational shift did not necessarily entail adoption of boat people identity, as shore-based fishers maintained distinct social status from boat-dwelling communities. This distinction is crucial for understanding how the On Lung Ching Chiu ritual evolved—whether it represents appropriation by a distinct ethnic group or adaptation by the same community shifting occupational identities.

Fortunately, Hiroaki Kani (1967, 1972) dedicated several years to conducting anthropological fieldwork among Hong Kong’s boat-dwelling communities, aiming to identify their settlement patterns and social structures. His research holds immense significance, providing invaluable primary sources about the lifestyles and spatial dynamics of these communities during the post-war era, filling a crucial research gap noted by Anderson (1970).

He Xi and David Faure (2015) discussed the difficulties in studying the histories of boat-dwelling communities in South China, stemming from the lack of written records from these marginalized groups and existing accounts potentially influenced by land-dweller biases. They questioned whether modern ethnographic subjects descended from the historical ‘Dan’ boat people, given the movement between boat and land over time. They highlighted regional variations that challenged universalizing boat population experiences and argued that ethnic labels like ‘Dan’ became imprecise stereotypes detached from their literary origins. According to their writings, the mobility, limited sources, localized contexts, and problematic categorizations posed obstacles in reconstructing coherent historical narratives and identities of these communities through texts and fieldwork alone. These challenges underscore the importance of ethnographic works like Kani’s in documenting the lived experiences and dynamics of boat-dwelling populations.

Building upon this foundational research, my study aims to contribute to the understanding of how boat people communities actively engage in cultural reproduction and identity formation through religious rituals. By focusing on the On Lung Ching Chiu festival in Kau Lau Wan, I explore how these communities negotiate their position within the broader sociocultural landscape of Hong Kong, particularly in relation to the dominant Hakka traditions. This approach highlights the agency of the boat people in appropriating and transforming ritual practices to assert their own cultural narratives.

The efforts of historians, anthropologists, and sociologists in studying the jiao 醮 festival have yielded a wealth of ethnographic reports, documentation, and photographs collected by scholars and amateur researchers since the 1980s (C. Choi, 1990). This body of work provides invaluable insights into the rural societies of Hong Kong and China. For instance, Choi (2003) used the Jiao festival as a case study to explore the social mobility of boat people communities in Cheung Chau, illustrating the research significance of fieldwork centered on community festivals and rituals.

Building on this, Cai Zhixiang (2011) studied the On Lung Ching Chiu festival in Kat O, another island in Hong Kong’s New Territories. Cai discovered how the boat people there learned from, assessed, and selectively adopted practices of the surrounding land-based Hakka communities. Through emulating local Hakka customs—such as practicing Hakka rituals, establishing clan genealogies, and creating ancestral halls—the boat people constructed their own cultural and social boundaries. This process allowed them to differentiate themselves from being perceived merely as fishers. By participating in localized Hakka rituals like the On Lung Ching Chiu, and adopting Hakka-style institutions, the boat people of Kat O engaged in a form of cultural mimicry. Cai’s research reveals how these communities strategically integrated selected customs from their land-based Hakka neighbors, cultivating a distinct identity by appropriating aspects of the dominant local culture.

The present article examines how the boat people of Kau Lau Wan utilize the agency of religious rituals to position the cultural boundaries and discourse within their own community. On the one hand, this serves to obscure the presence of the original Hakka inhabitants of the village. On the other hand, it leverages various spatial and ritual expressions during the festival period to manifest their own social and cultural space, thereby reinforcing their distinct identity. Notably, national borders and boundaries do not hinder the continuity of their religious beliefs.

Using the case study of the On Lung Ching Chiu festival, this research explores how subaltern groups shape their traditional religious practices by referencing the perspectives of surrounding populations. In doing so, they seek to transcend formal regulations and community customs, ultimately asserting their own legitimacy and validity within the local context. Elements of their past that were previously viewed as morally incompatible gradually disappear from public view through the articulation of their religious beliefs. This illustrates how grassroots and minority communities exhibit creativity and agency when confronted with dominant religious and cultural influences. It provides a new perspective for understanding the pluralistic religious landscape of Hong Kong, where subordinate groups can autonomously construct and reconstruct their cultural boundaries within the religious domain, moving beyond simplistic state-local dichotomies.

On Lung Ching Chiu in Kau Lau Wan

The On Lung 安龍 ritual, traditionally performed by Hakka ritual specialists, is a significant community temple building activity in the New Territories, alongside the Tai Ping Ching Chiu (Wei, 2014). Although Kau Lau Wan village historically had a Hakka population, the majority of its residents were fishers. An interview with Mr. Chen, an elder from Kau Lau Wan, conducted by the I Care Project at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, highlights the distinct identity of the village’s inhabitants:

We in Kau Lau Wan are mostly all fishers, so we raise fish and eat fish, we really have fish in every meal! We’re not like the Hakka people, we don’t raise pigs and cattle, so we rarely eat other meat. When we went fishing, we would also sail a boat to Sai Kung to buy vegetables. (Chen, 2016)

This recollection clearly demonstrates that the Kau Lau Wan people identify themselves as fishers, distinct from the Hakka identity.

The settlement history of Kau Lau Wan village reveals a gradual demographic shift over the past two centuries. Originally dominated by Hakka people, the village saw an influx of fishers settling in the area alongside the existing Hakka population around two hundred years ago. Oral history interviews conducted by the I Care Project suggest that the fishers in Kau Lau Wan often married people of different ethnicities from neighboring island villages, such as Mrs. Du, who was originally from Tap Mun (Chen, 2016). This practice of intermarriage with other islands allowed the fishers to expand their population and strengthen their community ties.

However, the 1950s and 1960s marked a turning point for Kau Lau Wan and other villages in the New Territories. As the fishing industry declined and could no longer sustain the villagers’ livelihoods, many began to seek economic opportunities overseas. Zhang Shaoqiang (2016) observed a similar trend in Tai Shue village in Feng Tau Heung, Yuen Long, where the economic transformation of post-war Hong Kong led villagers to migrate to the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Consequently, the permanent resident population of Kau Lau Wan, like other villages, has dwindled to only a dozen or so people today.

Despite this dispersal of the original village community, the cultural traditions and rituals, such as the annual On Lung Ching Chiu festival, continue to hold significance. When village matters related to temple ceremonies arise, the scattered Kau Lau Wan villagers, now residing in Sai Kung town or other areas, still make the effort to return to the village to hold meetings and contribute. This is evidenced by the donation plaques inside the Tin Hau Temple, which record contributions made in British pounds and euros, reflecting the transnational mobilities of the Kau Lau Wan diaspora. Even as the villagers adapted to new economic realities by emigrating overseas, they have maintained their ties to the village and its longstanding ritual practices.

The historical records indicate that since 2001, Kau Lau Wan village has employed Chan Kwan, a Taoist priest from the Walled Villages of the New Territories, to preside over the festival rituals (Li Z. T. & Lai, 2007). Unlike other walled villages in the New Territories or festivals on Cheung Chau, the On Lung Ching Chiu festival in Kau Lau Wan has a relatively shorter duration. While the various ritual elements are more streamlined, the festival is essentially an adapted version of the Hung Man Ching Chiu, rather than a full-scale Tai Ping Ching Chiu or the traditional On Lung Ching Chiu. Prior to 2001, the village head noted during interviews that the ritual presiding duties were handled by Tse Kwok-kwan from Hou Chung, but the exact date is unclear. Tse Kwok-kwan was a local Taoist priest who had participated in the Tai Ping Ching Chiu festival in Hou Chung, which shows that although Kau Lau Wan uses the name ‘On Lung’, the rituals are actually closer to the Guangdong Hung Man Ching Chiu or Tai Ping Ching Chiu, with local Taoist priests presiding over the ceremonies in the past. (Li L. & Zheng, 2014).

The structure and content of the On Lung Ching Chiu festival in Kau Lau Wan share similarities with the general Tai Ping Ching Chiu rituals found in other New Territories walled villages, rather than the Hakka-style rituals. However, the village has incorporated the distinct On Lung element, which is considered the most crucial aspect by the Kau Lau Wan community. Historical newspapers indicated that the festival was previously held on the 7th and 8th days of the fifth lunar month in 1980 and 1987 (“Kau Lau Village Holds the An Lung Ching Chiu, Overseas Villagers Return to Celebrate the Traditional Festival Together,” 1987; “The Grand Festival in the North Sai Kung District of Kau Lau Wan, the An Lung Ching Chiu Dramatic Performance Is Lively, the People’s Livelihood Has Seen Gradual Improvement,” 1980). According to the current village head, the festival has been rescheduled to the 7th and 8th days of the fourth lunar month in the last three iterations (2001, 2008, 2015) due to the frequent typhoons that occur during the fifth lunar month.

In anticipation of travel restrictions that would prevent some villagers from returning to participate in the upcoming festival scheduled for late 2021, the village elders made adjustments to the cup-drawing ritual (打杯). Certain male members were excluded from this particular ritual element due to their anticipated inability to attend. This potential for the cup-drawing ritual to serve as a gatekeeping mechanism reveals a degree of deliberate manipulation to ensure the smooth execution of festival activities. Fortunately, travel restrictions were lifted in May 2023. During the observation process, I noted that many villagers expressed having just returned from abroad to participate in this grand event, reflecting the high regard numerous villagers hold for the On Lung Ching Chiu festival.

Traditionally, the On Lung Ching Chiu or Tai Ping Ching Chiu 太平清醮 is a local religious ceremony to purify the community. Through various Taoist rituals performed by Taoist priests, along with secular activities carried out by villagers, the village is cleansed. One of the constant practices in the On Lung Ching Chiu ritual involves the Taoist priests leading the village’s yuan shou 緣首 (village representatives) to perform the xing chao 行朝 (paying respects to the gods) within the boundaries of Kau Lau Wan village. Xing chao is a ritual where the Taoist priest conducts religious practices at locations marked by erected flagpoles, offering confessions to the deities on behalf of the villagers. Generally, the scope of xing chao corresponds to the community boundaries of the village. In Kau Lau Wan village, the flagpole locations are situated at three piers and near the mountaintop within the village boundaries. This practice evidently does not regard the land as a spatial concept but instead perceives the sea as the sole channel for entering the village (with some village houses excluded from this area). It is apparent that the scope of the da jiao 打醮 (Taoist ritual) is clearly oriented towards the maritime life of the community.

This simplified jiao ritual still preserves some typical jiao practices, including the nighttime jingwu 禁武 ritual to expel evil spirits. Additionally, it encompasses the qibang 啟榜 ceremony, symbolizing community participation, as well as the fangsheng 放生 ritual of releasing captive animals, representing the accumulation of merits. It also features the ritual of offering food to wandering ghosts and the concluding jidayou 祭大幽 ceremony for the restless spirits. However, due to the impact of the pandemic on the villagers’ fundraising abilities, they opted to forgo inviting a deity-offering opera troupe. Instead, they maintained the opera stage and invited singers to perform Cantonese operatic songs and pop songs. The fundamental ritual characteristics of the On Lung Ching Chiu in Kau Lau Wan village bear striking similarities to the religious practices of terrestrial residents, particularly those of the walled villages in the New Territories. However, certain nuances in the rituals reflect the aquatic inhabitants’ attempts to articulate their maritime consciousness and aquatic way of life.

The On Lung is the most important ritual within the On Lung Ching Chiu festival. Traditionally, it involved using a live duck and live chicken bound together with red cloth to represent the dragon’s body, which would then be taken to a large rock in the village to perform the ritual, ensuring the well-being of the villagers. However, in 2023, the villagers were unable to find a live duck for the dragon’s head, and following the advice of the Taoist priest, they opted to use an old qilin dance head instead, connecting it to a red cloth approximately 18 feet and 8 inches long with a live chicken at the other end. Since the dragon cannot be placed on the ground, the ‘dragon body’ was held by a young male villager responsible for the dragon dance, with the dragon head placed on the altar, awaiting the start of the On Lung ritual (Figure 1). During the observed ritual, only five villagers participated in the On Lung, and the dragon body was carried down the mountain in the form of a lion head and chicken tail, differing from the 2015 iteration. This adaptation of the dragon body’s composition in the On Lung ritual showcases the villagers’ flexibility in maintaining the essence of the tradition while accommodating practical constraints. The substitution of the live duck with a qilin dance head demonstrates the community’s resourcefulness in preserving the symbolic significance of the dragon body, even when faced with challenges in procuring the customary elements.

Although Kau Lau Wan is primarily a fishing village populated by boat people, the villagers still place great importance on the On Lung tradition, which they perceive as a crucial Hakka ritual. This intriguing coexistence of Hakka cultural elements within the boat people community warrants further exploration of the associated religious phenomena.

The Obscured Hakka Elements

The On Lung Ching Chiu festival is often thought of as an inherently Hakka cultural practice, but over the past few decades, the Hakka ethnic elements within this ritual have become obscured. The assumption that the On Lung ritual is of Hakka origin is grounded in ethnographic and historical studies of religious practices in the New Territories of Hong Kong. Scholars such as Wei (2014) have documented that the On Lung Ching Chiu festival is a significant Hakka ritual performed in various Hakka villages in the region. The ritual centers on land-based beliefs, emphasizing the prosperity and blessings of the land, which is a characteristic feature of Hakka religious traditions. In Hang Tau Village, Sheung Shui, for example, the On Lung ritual is closely associated with the concept of Wang Tu Xu Fu 旺土許福, focusing on nurturing the land’s vitality (Wei, 2014).

Furthermore, Cai Zhixiang’s (2011) research on Kat O, an island with a significant Hakka population, highlights the presence of a dragon vein (龍脈) believed to traverse the island. The On Lung Ching Chiu ritual there is performed to ensure the vitality and strength of this dragon vein, again underscoring its Hakka roots. These studies provide substantial evidence that the On Lung ritual is traditionally associated with Hakka communities, which justifies the assumption made in this research.

Despite the On Lung ritual’s strong association with Hakka traditions, reports suggest that in Kau Lau Wan, the origins of the festival as a Hakka practice have been overshadowed by the community’s transformation over the past few decades. According to a report in the Huaqiao Ribao 華僑日報 (Overseas Chinese Daily News) on June 22, 1980, the festival in Kau Lau Wan first emerged in 1931. The original intent behind organizing the festival was stated as follows: “More than fifty years ago, due to villagers falling ill, a sense of unease among the population, and the risks encountered at sea, the villagers gathered to collectively decide on organizing the On Lung Ching Chiu ritual” (“The Grand Festival in the North Sai Kung District of Kau Lau Wan, the An Lung Ching Chiu Dramatic Performance Is Lively, the People’s Livelihood Has Seen Gradual Improvement,” 1980). This rationale aligns with the purposes behind the Tai Ping Ching Chiu festivals held in other parts of Hong Kong. However, if the On Lung ritual is traditionally a Hakka practice, the origin story described in the news report seems to have little connection to Hakka customs and instead resembles more of a fishing community tradition.

Furthermore, some other news reports from the 1980s regarding the On Lung Ching Chiu festival in Kau Lau Wan reflect that the fishers were remitting funds from overseas to support the festival and community development. These overseas remittances not only helped improve the Kau Lau Wan community’s environment but also contributed to a more vibrant festival celebration. From this perspective, the fishers’s financial resources allowed them to assert their own interpretive authority and discourse over the On Lung Ching Chiu ritual in the post-1980s period, with no further mention of Hakka elements appearing in the reports or the villagers’ recollections. In other words, the On Lung Ching Chiu festival has become a shared community ritual for the Kau Lau Wan fishers to articulate their own identity. With the exception of retaining the term ‘On Lung’ and making some adjustments to the ritual itself, the Hakka presence has been effectively marginalized within this festival.

According to the 2001 donation plaque from the Tin Hau Temple’s On Lung Ching Chiu, only two members of the Liu surname, which is commonly associated with the Hakka ethnic group, made contributions. By 2008 and 2015, only one Liu surname member had donated, further indicating the disappearance of the Hakka presence from the Kau Lau Wan On Lung Ching Chiu community. This evolution suggests that the fishers, through their economic resources and social networks, have been able to gradually assert their own agency in reshaping the ritual, effectively obscuring the original Hakka cultural elements that may have been associated with the festival in the past. The disappearance of the Hakka presence within this community ritual warrants further exploration and analysis.

The available literature and oral history sources do not clearly indicate the extent of Hakka villager participation in the On Lung Ching Chiu festival. There is also no information on how the originally Hakka-associated On Lung Ching Chiu ritual transformed into the current Tai Ping Ching Chiu–style format presided over by Taoist priests from New Territories traditions. From an external environmental perspective, Hakka priests had largely disappeared from the community by the 1990s, leaving the village with no choice but to shift to the Taoists priests from New Territories tradition. In fact, as mentioned by the village head, while the Taoist masters overseeing the rituals have changed over the past few iterations, they have all been from the New Territories tradition, such as Guo Daoyuan 郭道院, documented by Wei Jinxin (2014) and the Daoist Tse Kwok-kwan recalled by the village head.

Therefore, Hakka involvement may have been limited to the earliest unrecorded iterations of the festival. As the fishing community’s overseas remittances gained media attention and their financial resources drove the renovation of the Tin Hau Temple and the festival planning, it becomes evident that the Kau Lau Wan fishers did not gradually integrate into a pre-existing Hakka On Lung Ching Chiu ritual. Rather, they utilized and emulated Hakka ritual standards to recast the On Lung Ching Chiu as a medium for articulating their own community discourse and self-identification.

This suggests that the Hakka cultural elements have been progressively obscured, as the fishing community has assertively reshaped the ritual to reflect their own social and economic agency within the community, rather than simply adopting a pre-existing Hakka tradition. The gradual erasure of the Hakka presence within this ritual warrants further investigation to fully understand the dynamics of cultural transformation and the negotiation of community identity.

During the fieldwork, the author noticed that a villager with the Liu surname was recorded on the ‘Blessed Name List’ (人緣榜) and took the opportunity to inquire with the village head about the role and identity of the Hakka people in the village. However, the village head indicated that this Liu surname villager was not actually Hakka, but rather someone who had moved in from Yau Oi Teng and was not part of the local Hakka community. The village head quickly diverted the conversation, further confirming that the fishers do not perceive the previously resident Hakka population as having any significant relevance to the ritual. This exchange suggests a deliberate attempt by the village head to distance the current community from any direct Hakka associations. The swift redirection of the conversation and the dismissal of the Liu surname villager’s Hakka identity implies a conscious effort to obscure or marginalize the Hakka presence within the village’s historical and cultural narratives.

This interaction provides additional evidence of the fishing community’s agency in redefining the cultural significance and ownership of the On Lung Ching Chiu ritual, effectively erasing or downplaying the Hakka elements that may have been integral to the festival’s origins. The village head’s response underscores the fishers’s concerted efforts to assert their own community identity and ritual practices as the dominant cultural framework, rather than acknowledge the historical Hakka influence. This dynamic warrants further exploration to fully understand the processes by which minority cultural elements become systematically obscured or displaced within the evolving community narratives and ritual practices of dominant social groups over time.

The On Lung Ching Chiu festival has undergone a process of localization, where most of the rituals have been ‘fisherized’. However, at the same time, certain ‘fishing community elements’ have also been incorporated into the secular activities. Starting from the deity invocation, dozens of women from the village form a ‘land-based dragon boat’ that follows behind the Taoist priest, the ritual leaders, and the other participants (Figure 2). This land-based dragon boat has only emerged in recent editions of the festival, with three teams participating in the 2015 iteration. These women are mostly residents of Kau Lau Wan village who have moved out but return specifically for the two-day festival to assist in the celebrations.

The tradition of land-based dragon boat racing originates from the Hoklo people’s wedding customs, as rowing boats holds symbolic significance for fishing communities, representing auspicious rites of passage. While the On Lung Ching Chiu festival is not directly related to family celebrations, the incorporation of the dragon boat ritual has served to enhance the festive atmosphere. According to reports from the 1980s, this land-based dragon boat procession was not present in the past, and the inclusion of women’s participation in these celebratory rituals is a more recent development. On the other hand, the integration of this maritime-related celebratory activity into the On Lung Ching Chiu ritual further fisherizes the overall religious tradition, allowing the fishing community to assert a greater sense of ownership over the festival.

The positioning of the ritual banners (幡竿) also reflects the fisherization of the On Lung Ching Chiu. Typically, the banners symbolize the spatial boundaries of the village community and the domain under the deities’ jurisdiction. (C. C. Choi, 2003) In Kau Lau Wan, while one banner is placed on the mountainside, the other three are erected at different piers in the village. This spatial arrangement clearly positions Kau Lau Wan as a fishing community, rather than a Hakka agricultural settlement.

In fact, the neighboring Tan Ka Wan village, which had a Catholic church built in the 19th century and is documented in the Map of Xin’an County, is excluded from the ritual banner boundaries, indicating the Kau Lau Wan fishing community’s desire to disassociate itself from this other local identity.

This aligns with Cai’s (also known as Choi C. C.) observation in ‘Emulating the Other’ that the key to establishing one’s own ethnic identity involves on the one hand, becoming part of the nearby majority and mainstream, and on the other hand, drawing a clear line with the minority around them." (Cai & Choi, 2011). The Kau Lau Wan fishers have not only participated in and emulated the practices of the shore-based communities, but have also deliberately emphasized the fishing community’s characteristics in their spatial arrangements, financial investments, and ritual structures, effectively replacing the Hakka traditions and shaping Kau Lau Wan as a distinctly fishing village.

The Obscured Cultural Spaces

This blurring of identity and the relationship with the community space was also observed during the field research. During the author’s visit in May 2023, the author and research team members were invited to have a vegetarian communal meal (or poon choi, 盆菜) with the villagers. Some enthusiastic amateur researchers who were conducting independent explorations joined the villagers at the shared tables, engaging in conversations about childhood memories and sharing details about the lively festival.

At one point, another researcher asked a female villager who was born and raised in Kau Lau Wan in the 1960s, “Did you all live on boats back then?” The woman’s demeanor immediately shifted from the previously harmonious discussion, and she became visibly irritated, creating a rather tense atmosphere. In her response, the researcher noted that the villager was deeply offended by the implication that they had lived on the water rather than in the village. Emphatically, the villager stated, “We had very large houses, we had our own village. How could we have lived on boats? If you don’t believe me, I’ll take you there to see it!”

This researcher appeared to have overlooked the value the villager placed on their identity and living arrangements. However, this incident, unrelated to the festival rituals, revealed that the boat people have long been associated with maritime work: The villager mentioned that she had assisted with fishing and handling the catch as a child. Yet, they now view the sea, the very domain they once depended on for their livelihoods, as an undesirable living space, and consider residing in houses or villages as a representation of their community status and prestige.

This aligns with B.E. Ward’s (1965) observations in the 1960s, which mentioned that there were an estimated 2-3 million boat people across Guangdong, with around 150,000 in Hong Kong, 100,000 of whom lived on boats. Ward also noted that boat households were already starting to consider settling their elderly or school-age children on land. Cai’s (2011) work further elaborates that the fishers began moving ashore in the 1950s. While the perspectives of other boat people communities may have varied, it is evident that the Kau Lau Wan boat people are attempting to obscure their historical ties to the maritime environment within the context of this large-scale community religious festival.

The distinction between ‘fishers’ and ‘boat people’ emerges as a crucial factor in understanding identity formation in Kau Lau Wan. While both groups engaged in fishing activities, their social status and cultural identification differed significantly. Shore-based fishers, including those of Hakka origin, maintained a respectable social position within the broader community. In contrast, the label of ‘boat people’ carried historical stigma associated with water-dwelling lifestyles. This distinction helps explain why current Kau Lau Wan residents strongly emphasize their identity as land-based fishers while distancing themselves from associations with boat-dwelling traditions, even as they maintain maritime-oriented ritual practices.

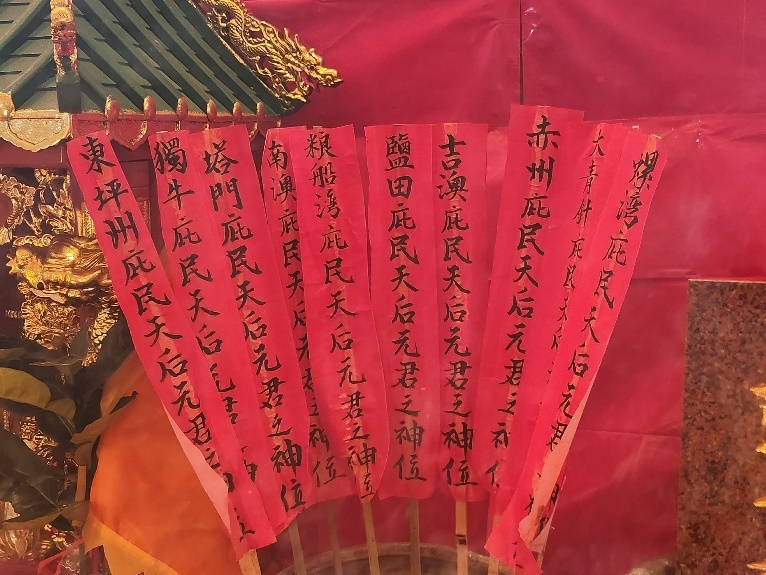

In a typical Tai Ping Ching Chiu festival, the nearby community deities are usually invited to participate in the rituals, and the case of Kau Lau Wan is no exception. However, due to the village’s remote location and poor transportation, the deity invocation rituals cannot directly summon the gods from different areas. Instead, they utilize the practice of ‘paper flying’ (紙飛), where the Tin Hau deities from the neighboring communities are represented through textual invocations and brought into the ritual altar (Figure 3).

For the 2023 On Lung Ching Chiu festival, which was postponed from 2022, the Tin Hau deities from fishing village communities in eastern Shenzhen and Huizhou, such as Nan’ao南澳, Yantian鹽田, and Daqingzhen (大青針 Pedra Blanca), were all invited to enter the ritual altar. This suggests that the historical networks of fishing village communities did not have rigid boundaries, but rather constituted a fluid and expansive maritime community network that could be easily accessed and mobilized.

The case of Daqingzhen, also known as Zhentouan Rock針頭岩 or Daxingzhanyan大星簪岩, is particularly noteworthy. This uninhabited island is administered by Huizhou City’s Huizhou County, and it has been documented in Zheng He Fleet’s navigational charts (Zhu & Lee, 1988). Daqingzhen is located approximately 80 kilometers in a straight line from Kau Lau Wan, a distance that would have been difficult to imagine connecting with the village’s ritual practices (Figure 4).

During discussions with the village head and senior villagers, the researcher learned that the fishers used to travel to the Daqingzhen area for fishing, and they had even established a small Tin Hau shrine on the island (Luo, 2024, pp. 48-50). This suggests that the maritime connections and mobility of the fishing communities extended beyond the immediate geographic boundaries, allowing them to maintain ritual and social networks across vast distances along the coastline.

The incorporation of deities from these far-flung fishing villages into the Kau Lau Wan On Lung Ching Chiu festival demonstrates the fluidity and expansiveness of the boat people’s community identity and religious practices, transcending the limitations of land-based spatial configurations and administrative boundaries. This highlights the importance of understanding the boat people’s social and cultural world through the lens of their maritime-oriented lifeways and networks.

The practice of inviting distant fishing village deities to participate in the Kau Lau Wan On Lung Ching Chiu festival underscores the cross-boundary network connections within the fishing community. This reflects the Kau Lau Wan fishers’ attempts to strengthen their identity and status as a ‘fishing community’ by expanding the scope of their ritual practices.

In contrast to the typically localized deity veneration found in general Tai Ping Ching Chiu or Hakka-associated On Lung Ching Chiu rituals, the approach taken in Kau Lau Wan embodies the fishing community’s efforts to transcend geographical boundaries and cultivate a fluid, boundaryless maritime community consciousness. This self-positioning as a ‘fishing community’ resonates with the earlier discussion of how the fishers have ‘fisherized’ the On Lung Ching Chiu ritual to assert their own standing within the local context.

Through the cross-boundary expansion of their deity veneration networks, as well as the reshaping of the local ritual, the Kau Lau Wan fishing community has effectively constructed and reinforced its distinct cultural identity as a prominent community subject. This reflects how they have leveraged cultural means to defend and rearticulate their own boundaries and discursive power when confronted with ‘external’ groups like the Hakka people.

By asserting their maritime-oriented ritual practices and social networks, the Kau Lau Wan fishers demonstrate their agency in navigating the complex dynamics of identity formation and cultural belonging. This underscores the importance of understanding the boat people’s lifeways and community narratives from the perspective of their fluid, transboundary existences, rather than through the lens of more static, land-based frameworks.

The exploration of the ‘obscured domain’ in this case study reveals how the Kau Lau Wan fishing community has leveraged religious ritual spaces to reinforce their identity as a ‘fishing community’. The villagers’ deliberate attempts to blur their past image as water-dwelling people dependent on the maritime environment, instead emphasizing their settlement within the village, reflects their desire to position themselves in a socially superior status—one that is idealized as living on land rather than on boats.

At the same time, the community has actively expanded its cross-boundary deity veneration networks, seeking to cultivate a fluid, boundaryless maritime community consciousness. These cultural practices collectively point to the fishing community’s efforts to reconstruct their own community subjectivity.

In the face of other social groups, the Kau Lau Wan fishers have successfully established their dominance by strategically obscuring and redefining the ritual spaces. Through this process of ‘domain obfuscation’, they have effectively asserted their position as the leading group within the local context.

This dynamic underscores the fishing community’s agency in navigating complex identity politics and power relations. By simultaneously reshaping their ritual practices and expanding their social-ritual networks, the Kau Lau Wan fishers demonstrate their ability to actively rearticulate their cultural boundaries and discursive authority, even as they confront the historical presence of other groups like the Hakka.

Conclusion

Building on Liu Yonghua’s reinterpretation of B.E. Ward’s perspectives (Liu, 2009), this study provides new insights into the importance of not underestimating the agency of folk groups when analyzing religious rituals. The evolution of the On Lung Ching Chiu festival in Kau Lau Wan demonstrates how the boat people community actively reshaped a ritual tradition that originally belonged to the Hakka people, transforming it into a crucial medium for reinforcing their own community identity.

The adjustments to the ritual content, the changes in spatial arrangements, and the incorporation of cross-border fishing community networks all reflect the agency and creativity of the boat people group. This aligns with the three cognitive models proposed by Ward in her study of the boat people in Kau Sai Chau. The original On Lung Ching Chiu festival may have reflected the Hakka people’s ideological model, but over time, the boat people gradually replaced this with their own models of everyday life and insider observer perspectives, successfully ‘fisherizing’ the ritual and obscuring the original Hakka cultural elements. Through the agentic reshaping of the religious ritual, the boat people consolidated their status as the predominant group in Kau Lau Wan.

This research illustrates the creativity and proactiveness of subaltern and minority groups when faced with mainstream religious and cultural influences, providing a new perspective for understanding the pluralistic religious landscape of Hong Kong. The actions of the boat people community demonstrate the importance of recognizing folk agency, moving beyond a simplistic state-local dichotomy and affirming that grassroots groups can utilize autonomy within the religious domain to construct and reconstruct their own cultural boundaries.

The findings from this case study contribute to a deeper understanding of how minority or marginalized communities can employ creative cultural strategies to assert their own narratives and social standing, often by strategically blurring or redefining the very spaces and boundaries that have been used to circumscribe them in the past. The processes of cultural transformation and identity negotiation observed in Kau Lau Wan find parallels in other maritime communities across the Pearl River Delta region. For instance, boat-dwelling fishers in Tai O (Hong Kong) and Macau maintain the annual Zhu Daxian 朱大仙 ritual performed aboard their vessels. Like the On Lung Ching Chiu in Kau Lau Wan, these rituals serve as powerful markers of marginal community identity while simultaneously challenging fixed geographical and cultural boundaries. These rituals, performed on boats rather than in land-based temples, represent both the practitioners’ distinct maritime identity and their fluid, mobile existence between water and land (Zheng & Chen, 2013). These parallels suggest a broader pattern among Pearl River Delta fishing communities, where religious practices become sites for negotiating complex identities and asserting cultural agency despite marginalized status. Such comparative examples strengthen our understanding of how subaltern maritime communities actively reshape and maintain their cultural practices to articulate distinct identities while navigating changing social and economic circumstances. The transformation of the On Lung Ching Chiu in Kau Lau Wan thus represents not an isolated case but part of a wider phenomenon of cultural adaptation and identity formation among maritime communities in the region.

The case of the On Lung Ching Chiu festival in Kau Lau Wan sheds light on broader issues of cultural identity, heritage preservation, and the dynamics of power within marginalized communities. It emphasizes the need for a more nuanced understanding of how religious practices serve as sites of negotiation and contestation among different groups. Future research could further explore comparative cases in other regions, examining how similar processes of cultural adaptation and identity formation unfold in diverse sociocultural contexts.

Funding

This work was supported by Research Grants Council, University Grants Committee, HKSAR [Grant Number UGC/FDS16/H08/23].

.png)

.png)