Introduction

Renowned for its linguistic diversity, Taiwan has long been regarded by linguists as the cradle of the Austronesian-speaking world. The island’s original inhabitants—the Austronesian peoples—have, over the centuries, endured successive waves of colonial intrusion and political transformation under the Dutch, the Spanish, the Qing Empire, the Japanese, and later the postwar period. Each regime imposed its own systems of extraction and governance, continually restructuring and reimagining Indigenous social organization in the name of trade, civilization, and control. From early colonial classifications that crudely distinguished between ‘raw’ and ‘civilized’ tribes according to their proximity to centers of power, to ethnological surveys that administratively categorized Taiwan’s Indigenous peoples into nine groups, and finally to the movements for ethnic self-awareness that gained force during the 1990s, Indigenous identity in Taiwan has been repeatedly redefined through external and internal processes of recognition. Today, seventeen Indigenous peoples are officially recognized—including the Siraya, whose decades-long campaign for ethnonymic recognition, initiated in 1990, was formally acknowledged only on October 17, 2025. This enduring sequence of foreign rule and state intervention constitutes a long and multifaceted history of colonial domination that continues to shape Indigenous society in Taiwan today.

Following this long history of colonial domination, Taiwan’s Indigenous societies have undergone successive waves of sociocultural transformation. From the Japanization policies (1937–1945) and postwar land reform (1949–1953), to the Mountain People Life Improvement Movement’ of the 1950s–1960s and the forced relocation and resettlement after Typhoon Morakot in 2009, these communities have been subject to complex processes of localization, modernization, and even disaster-induced disruption. Within the frameworks of state governance, Indigenous peoples’ relationships to their ancestral territories have been reshaped, thereby affecting the foundations of social organization. However, during the 1980s and 1990s, a series of Indigenous movements in Taiwan sparked a broader wave of ethnic self-awareness. The Name Rectification Movement (1984) challenged colonial terminology and achieved the formal recognition of ‘Indigenous peoples’ in 1994. The Return Our Land Movement (1988) demanded the restoration of ancestral territories seized through colonial and state regimes. The Restoration of Traditional Names campaign (1995) reclaimed cultural sovereignty by reinstating Indigenous naming rights. Together, these movements confronted enduring colonial structures and marked a turning point in which Taiwan’s Indigenous peoples actively reconstructed their collective identity and renewed their relational ties to ancestral land. Building on the momentum of ethnic self-awareness that emerged during the 1980s and 1990s, Indigenous peoples in Taiwan have continued to resist exploitation and discrimination. Through what James Clifford (2013) terms ‘historical practice’, —a mode of engaging with the past as a living, adaptive process through which Indigenous peoples actively reinterpret ancestral knowledge and negotiate their position in the contemporary world—Taiwan’s Indigenous peoples have actively worked to reestablish connections between land and cultural revitalization, crafting local lifeworlds that are at once traditional and contemporary.

Engaging in political participation, literary production, and artistic expression, Indigenous communities have carved out multiple, inside-out pathways to reclaim subjectivity in the contemporary moment. Simultaneously, they have leveraged state resources to implement externally-supported initiatives—such as community revitalization programs, community forestry projects, and more recently, COVID-19 stimulus-funded landscape improvement schemes. These efforts aim to investigate, plan, and articulate the ecological and cultural distinctiveness of their local environments. Rather than simply invoking a rhetoric of cultural revival, such engagements attempt to reconstruct the contours of everyday life through diverse mediations and modes of spatial reimagination. However, neoliberal modes of resource allocation and cultural governance have produced uneven distributions of resources and authority within Indigenous communities, generating divergent perspectives on what constitutes ‘tradition’ and ‘cultural revitalization.’ These interpretive differences have become increasingly visible under externally funded cultural programs, revealing the tensions among cultural representation, economic aspiration, and the lived practices of identity. These tensions complicate Indigenous communities’ negotiations with state and market forces, reflecting how neoliberal interventions reshape local interpretations of ‘tradition’ and ‘revitalization’ while reconfiguring the very grounds of cultural resilience (Dombrowski, 2002; Hale, 2002, p. 2006; Y.-K. Huang, 2018).

In response to these challenges confronting Taiwan’s Indigenous communities—including the fragmentation of traditional relations and the uneven impacts of neoliberal cultural governance— Taiwan’s Science and Technology Council launched the ‘Humanities Innovation and Social Practice’ (hereafter HISP) Project in 2012, under the auspices of its Department of Humanities and Social Sciences. Designed to re-establish channels of dialogue between academic institutions and local societies, this initiative encouraged universities to work collaboratively with local communities in confronting contemporary dilemmas, while fostering feedback loops between theory and practice grounded in place-based agency (Chou & Chen, 2019). Examining two phases of the program (2012–2015 and 2015–2018) across seven participating universities, Chou et al. (2018) employed an actor-network approach to analyze the dynamics of university–community interactions. They argued that universities should respect local subjectivities and situate projects within specific sociocultural contexts, developing open-ended, bottom-up actions that welcome diverse and heterogeneous actors. Through such collaborations, it becomes possible to weave local social fabrics and create flexible, situated networks of practice.

Nevertheless, given the diverse historical and cultural backgrounds of different communities—and the distinct visions that each university holds—the HISP, though unified in its overarching goals, must be adapted to specific local conditions. This diversity foregrounds a key question: how can universities engage in social practice that does not merely assist communities but strengthens their capacity for self-articulation? If we are to clarify what it means to integrate theory and practice, and to demonstrate how universities can collaboratively weave community networks by recognizing local heterogeneity, we must critically examine how communities transform and sustain their cultural foundations in concert with universities.

This article thus examines the case of the HISP Center at Taitung University, focusing on its engagements with Lalebaq tribe, a Paiwan community that exemplifies the broader trajectories of Taiwan’s Indigenous societies and is located in Taiban community, Daren Township, Taitung County. As one of the many communities navigating the legacies of colonial governance and contemporary revitalization discourses, it provides a lens through which to explore how the university sought to cultivate interactional models that resonate with both traditional and contemporary sensibilities by recognizing the cultural specificities of the region.

Building on Stuart Hall’s (1985) and James Clifford’s (2013) articulation theory—which respectively conceptualize articulation as a contingent process of linking elements within power-laden structures and as a historical practice through which Indigenous peoples actively negotiate the meanings of belonging and identity—this paper introduces the notion of ‘articubility’ to shift attention from the act of articulation to the capacity that makes such articulation possible. Whereas Hall and Clifford emphasize how connections are forged across difference, the concept of articubility foregrounds the relational competencies and socio-cultural conditions that must be cultivated prior to the act of rearticulation itself. Through this lens, the article examines how Indigenous communities cultivate the capacity for ‘articubility’ to reconfigure tradition and locality in the face of ongoing colonial legacies and contemporary pressures. It further explores how Indigenous communities strategically mobilize diverse resources and external opportunities to shape and enact this capacity for reconnection across difference, thereby re-embedding themselves within shifting local and sociopolitical landscapes.

Field Site and Social Context

This article takes the Lalebaq tribe as a case study to examine how articulability—the capacity to reconnect across difference—is generated through dynamic interactions between internal social structures and external collaborations. The Lalebaq tribe, a Paiwan settlement known for its hierarchy-based social structure, has actively cultivated collaboration with the Humanity Innovation and Social Practice Center at Taitung University (hereafter NTTU-HISP) since July 2019, seeking to address local concerns such as elder care, economic stagnation, and youth outmigration. At the heart of the community’s internal organization stands the P lineage, the core traditional leadership that exercises ritual authority and territorial stewardship through enduring practices of redistribution. In particular, during the millet harvest ritual, the P lineage collects agricultural produce from households and redistributes it to support vulnerable members of the community. This enduring practice between houses not only reinforces the lineage’s social authority but also reveals how the community itself organizes and mobilizes resources for collective well-being—a capacity that shapes the conditions under which relationships with external actors can be formed and sustained, and thus lays the groundwork for articulability to emerge.

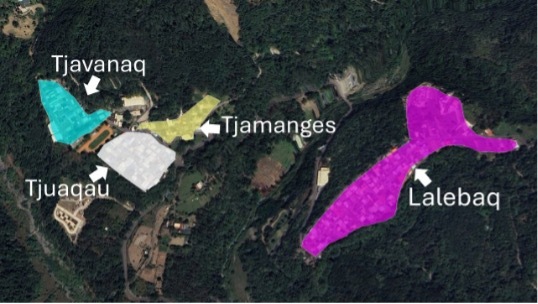

However, in 1954, three distinct Paiwan settlements—Tjavanaq (centered around the J lineage), Tjuaqua (jointly managed by the Y and C lineages), Tjamanges (led by the H lineage) —were relocated to live with Lalebaq tribe and consolidated into what is now Taiban community in Daren Township, Taitung County (see Figure 1). Based on patterns of kinship and spatial distribution, Taiban community can be further divided into the ‘Taiban settlement’, which includes Tjavanaq, Tjuaqua, and Tjamanges, and the ‘Lalebaq tribe’ which has retained its lineage-based traditional leadership. This arrangement brought together five historically significant lineages (J, C, Y, H, and P) into a newly constructed space, requiring formerly separate kin groups to renegotiate their social relations and confront conflicting claims over ritual authority, land rights, and leadership. This convergence has heightened tensions and produced contrasting interpretations of publicness and collectivity.

In the early stages of collaboration, NTTU-HISP sought to identify local needs and align university initiatives with community priorities. However, this process required careful navigation of Paiwan hierarchical relations. The Center worked to unpack the social structures among lineages to understand how different segments of the community conceptualized the idea of the ‘public’. Paiwan conceptions of publicness are grounded in lineage-based interactions and shaped by the spatial politics of house-based organization. As a society characterized by features of the ‘house society’ model, Paiwan communities often seek to reconstitute a shared sense of belonging when confronting relocation or reconstruction. This is achieved through efforts to maintain connections to ancestral lands, reinforce kinship networks, and enact ritual practices that reinforce the notion of precedence (Acciaioli, 2009; Forth, 2009; Fox, 1994, 2004; Lewis, 2006, 2016). By emphasizing genealogical priority, order of relocation, and sequence of house construction, these claims to ‘precedence’ not only reconstruct the temporal and spatial dimensions of social relations but also form the basis for lineage authority tied to land and ritual power. As Clifford (2013, pp. 13–15) points out, such articulations of precedence and ownership often reflect underlying power struggles.

After being designated a state-administered unit as ‘Taiban community’, articulations of precedence by traditional leaders have come to bear contemporary socioeconomic implications beyond their ritual obligations (e.g., rights to agricultural tribute or responsibility to conduct ceremonies). These include asserting leadership through participation in academic partnerships or applying for governmental subsidies. As NTTU-HISP entered the community with funding and institutional support, latent inter-lineage power dynamics began to surface, revealing increasing ambiguity around what counts as ‘local needs’ and ‘public interests.’ In this context, each lineage projected different expectations onto the HISP initiative, shaped by distinct interpretations of tradition and perceptions of present political-economic conditions. These divergent understandings of the ‘we-group’ required NTTU-HISP to remain constantly reflexive about the complexity of local actors and avoid privileging or neglecting particular families.

The redistribution and manipulation of external resources accompanying the project often became a means to maintain—or even reverse—traditional hierarchical structures. For example, certain individuals positioned themselves as ‘brokers’ of resources to demonstrate their influence over external capital. Through discourses of local identity framed from the perspective of a particular lineage, they reframed individual concerns as shared aspirations. Ritual performance, in this context, became a strategic arena for reconfiguring power, rendering narratives of ‘cultural continuity’ legible to both internal and external audiences. Whether as a form of interpellation by NTTU-HISP (in the Althusserian sense) or as an act of cultural-political performance, these practices reveal the multiplicity of local subject positions (Althusser, 1972). As Chen Wen-Hsueh and Chiu Yun-Fang (2017) argue, the interaction of historical events and cultural specificity has led Indigenous community-building efforts to prioritize the reconstruction of ethnic subjectivity. In practice, this often entails replacing the traditional category of ‘tribe’ with the administrative concept of ‘community’ to consolidate internal identity as a strategy for resisting colonial rule, post-disaster recovery, and economic transformation. However, this study recognizes that such processes of building locally driven momentum often generate tensions between competing notions of community subjecthood, making the categories of ‘community’ and ‘tribe’ both overlapping and mutually exclusive. This contradiction not only manifests in disputes over resource allocation but also renders ‘community subjectivity’ a persistently contested and unresolved issue.

Research Methodology

This study adopts an action research approach, in which the researcher—embedded as a full-time postdoctoral researcher at the NTTU-HISP—has conducted long-term engagement in community-based activities since July 2019. The research remains ongoing, reflecting a sustained and evolving collaborative process with the Lalebaq community rather than a one-time intervention. This positionality situates the researcher as both an observer and a participant, enabling a reflexive and intersubjective mode of inquiry that critically examines the dynamics between university-driven social practice and Indigenous community life.

Fieldwork consists primarily of anthropological participant observation, supplemented by unstructured interviews and collaborative workshops designed with local residents. A total of 28 community members were engaged in the research, including 8 young and middle-aged participants (aged 20–50) and 20 elders (aged 50–100). These interactions were conducted in both Mandarin and Paiwanese, with oral consent obtained prior to data collection. The data includes fieldnotes, audio recordings, genealogical discussions, ritual observations, and daily conversations. Funding for fieldwork, transcription, and logistical support was provided through the multi-year NTTU-HISP social practice grant.

Methodologically, this study is grounded in the notion of ‘thinking through action’ (D.-S. Chen, 2018; Tsai & Hsieh, 2018), which encompasses two interrelated dimensions. First, through sustained field engagement and ethnographic writing, the researcher examines how NTTU-HISP’s interventions are received, interpreted, and re-signified by community members within broader discourses of Indigenous development, cultural revitalization, and social practice. Second, by collaborating with residents in designing and implementing locally sensitive initiatives—from genealogy workshops to youth leadership activities—the study operationalizes theory through action, while simultaneously letting practical challenges reshape theoretical assumptions.

This interplay between theory and practice is observed through the lens of Paiwan kakudan (house-based relationality) as both an analytical framework and an intervention strategy. Fieldwork focuses on how local actors reimagine, negotiate, and reconstruct house-based relations amid shifting subsistence patterns under capitalism and globalization. Drawing on Clifford’s (2013) concept of ‘historical practice’, kakudan is examined not as a static cultural form but as an ongoing articulation process between tradition and modernity. Facing overlapping political, religious, and economic pressures, Indigenous communities continuously rework their ‘old/new’ boundaries and memories, generating place-based knowledge through practices of becoming rather than bounded territories (Cresswell, 2004; Pred, 1984).

The collected data—ranging from interviews to ritual participation—reveals divergent interpretations of concepts such as ‘publicness,’ ‘ritual,’ and ‘place,’ and how these notions are enacted and reconfigured across different social arenas. Through reflexive writing and iterative feedback with community members, this study assesses the impacts of its interventions and explores how research itself functions as a form of collaborative practice. Such an approach responds to an ethical imperative within action research that asserts: research is intervention.

Literature Review

Dynamic Boundaries of Community

In this research, kakudan (Paiwan house-based relationality) is central to understanding how social continuity and adaptability are mobilized within Lalebaq. As Lévi-Strauss (1983) proposes in his theory of ‘house societies’, the house functions as both a material and symbolic entity that mediates kinship, territory, and status. Building on this, Carsten and Hugh-Jones (1995) emphasize that houses are not merely physical structures but relational units that continuously reproduce social persons and collectives through time. In the case of Lalebaq, kakudan similarly serves as a nexus between ancestral continuity and contemporary rearticulation. By positioning kakudan within a wider theoretical framework of house-based societies, this study explores how relational infrastructures support the capacity for reweaving social bonds—what this paper conceptualizes as articubility.

For many residents, locality emerges through intimate interactions within a specific spatial field—accumulated through lived experience and childhood memory. These activities, relationships, and spatial familiarity coalesce to generate a shared sense of place, allowing the community to distinguish itself from others (Lapid, 1995; Tuan, 1990). Yet, as Wolfgang Sachs argues, all localities must ultimately be situated within broader global networks and shaped by what he terms ‘cosmopolitan localism’—a politics of localization embedded within global structures (as cited in Z.-C. Chen, 2010). Accordingly, when this study seeks to understand how traditional Paiwan spatial configurations—once centered on tribal leadership—were transformed into a community-based locality under forced relocation, and how novel forms of public consciousness have emerged in this process, it becomes essential to examine how actors traverse spatial constraints and construct new communal forms through interactions in contemporary life.

The notion of the ‘contemporary’ often carries a homogenizing force that dilutes local cultural particularities. Under the influence of neoliberal forces, the boundaries between everyday economic, political, and cultural life have loosened, as the movement of people, goods, and information accelerates—producing a globalizing tide that gradually erodes the distinctiveness of place (Beck, 2000). Intensified capital flows and the proliferation of mass media have rendered emotionally anchored lifeways increasingly fragile, making local societies more susceptible to fragmentation. Development is increasingly shaped by the logic of global capital, within which ‘spaces of place’ are penetrated and reorganized by ‘spaces of flows’ (Castells, 1994; Zukin, 1993). As the spatial scales of everyday life shift, Lalebaq residents—whether pursuing education or employment—are increasingly uprooted from their ancestral homes. Meanwhile, state governance has continued to unsettle traditional structures, producing hybridized lifeways that often reflect a homogenizing dynamic between global and local forces (Appadurai, 1996; Cronon, 1994; Meyrowitz, 1986). However, as Chen (2010) argues, even within tangled global political-economic systems, local actors retain the capacity to transform place into a space of memory, imagination, and identity.

While frequent interactions blur spatial boundaries, they also heighten one’s sense of place-based identity. Cresswell (2004) suggests that when global economic restructuring threatens local distinctiveness, people become increasingly conscious of what they value in place and strive to preserve—or even enhance—its uniqueness and competitiveness by emphasizing distinctions between self and others. Place-based heritage, rooted in specific historical trajectories, becomes not only a source of collective belonging but also a gateway through which outsiders encounter experiences framed as “authentic” and seemingly beyond modernity (Harvey, 1997). In examining this backward-looking impulse—an effort to resist the dominant ideologies of the present and to seek out ‘uncontaminated’ traditions—Relph (2008) argues that the desire for authenticity arises from the erosion of place by heightened mobility and the replicability of modern life. Chambers (2000) further notes that the modern urge to escape alienation paradoxically reinscribes modernity itself by fetishizing the ‘non-modern’, the ‘authentic’, and the ‘traditional’ through specific objects, places, and people. Under such circumstances, local residents frequently draw on paths of articulation to weave together tradition and the contemporary moment, repositioning themselves in relation to others.

Proximity to the Past in the Contemporary Moment

The concept of articulation first emerged in Stuart Hall’s pedagogical philosophy developed while teaching at the Open University in the UK. Hall’s model of ‘starting where the student is’ (Clarke, 2015) inspired this project’s approach to co-learning and curriculum development in response to social change. For Hall (1985), articulation functions as a coupling mechanism that links elements with no necessary relation into a provisional unity. Extending Hall’s concept, Clifford (2013) emphasizes that articulations are not spontaneous but strategically assembled ensembles that retain difference within unity. Understanding the dynamics behind articulation thus requires analyzing the cultural symbols and political collectivities that sustain it.

To understand how the internal heterogeneity intensified by the collective relocation that formed Taiban community is negotiated, this paper adopts James Clifford’s (2013) framework of Indigenous articulation to explore how collaboration between the Lalebaq tribe and NTTU-HISP generates the momentum needed for articulation. Before discussing articulation, Clifford (2013) first introduces a perspective of ‘disarticulation’ to analyze how Indigenous peoples critically reassess spatial and social relations constructed under the logic of state administration, exposing the cultural tensions and constraints embedded within. Under circumstances in which the original condition of collective relocation cannot be reversed, this methodological approach suggests that Indigenous communities often must re-evaluate the ‘safe distance’ they maintain from tradition. In the case of the Lalebaq tribe, local residents emphasize that ‘chosen’ rather than ‘invented’ traditions—anchored in the idiom of the house—enable rearticulations between a past grounded in the tribe and a present organized by the administrative community. Through this process, ‘locality’ is reimagined as a site linking contemporary geographic space to traditional social relations.

To understand how Indigenous actors cultivate emotional attachments that are simultaneously anchored in the past and responsive to the present, Clifford (2013) turns to a non-linear notion of temporality. His example of Saputik, a local museum founded by Tamusi Qumak Nuvalinga, demonstrates how memory can be recomposed and concretely performed as a strategy to reconnect past and future outside of linear historical schemes. Such practices do not oppose tradition and modernity but articulate politics, economy, and culture across internal and external domains, forming a contemporary subjectivity that remains connected to tradition.

Clifford further emphasizes the ‘power of place’ as a grounding force enabling Indigenous peoples to sustain continuity amid rupture. Yet, the relations between community and land are never static; people do not live in the same way on the same land across centuries. The place-based identities forged through ongoing negotiations between internal dynamics and external pressures embody the very nature of articulation (Clifford, 2013, p. 64). Although Lalebaq tribe was not relocated far from its ancestral lands, shifts in land–person and person–person relationships—due to marriage, migration, and governance changes—have produced what Clifford calls a simultaneous sense of rupture and connection. This tension shapes community relations in contradictory ways, compelling both Lalebaq residents and NTTU-HISP to avoid reinforcing existing factional divisions. Instead, both parties seek to simultaneously ‘learn from’ traditional notions of publicness and ‘learn with’ local actors to envision collective forms that respond to contemporary conditions. In doing so, they disarticulate state-framed locality and rearticulate what Clifford calls the ‘homeland’.

Although Clifford’s work has been critiqued for insufficient grounding in specific historical and cultural contexts (Bragdon, 2015; Field, 2014), his example of the Sugpiaq, Creole, and Alutiiq identities effectively illustrates how a community, across successive colonial and postcolonial periods, strategically forged subject positions aligned with shifting political contexts. Rather than restoring some essential, uninterrupted tradition, Alutiiq identity was forged through iterative disconnections and reconnections—what Clifford (2013) calls “forging a new unity” (pp. 225–243). While emphasizing ancestral connections and interhistorical linkages, Clifford argues that studying modalities of articulation allows for a nuanced understanding of the practical and contested nature of contemporary Indigenous cultural politics. This includes attending to how power shapes material-symbolic relations and how identities are continually constructed, dismantled, and reconstructed.

In the context of Taiwan, recent scholarship has used articulation theory to examine Indigenous revitalization of traditional values (e.g., Chang, 2022; Y.-H. Chen, 2021; Ma, 2020). However, this paper insists that equal attention must be paid to the notion of ‘disarticulation’ emphasized by both Hale (2002, p. 499) and Clifford (2013, pp. 46, 303–305). This perspective highlights how Indigenous engagements with modernity involve a dual dynamic: accepting (articulating) imposed categories while resisting (disarticulating) their constraints. Researchers must avoid conflating articulation with cultural revival and instead recognize that Indigenous communities continuously ‘rework’ both tradition and modernity. Through such practice, they disarticulate the dual structures that shape them and reweave subjectivities situated across multiple, often contradictory, discursive fields.

As Slack and Macgregor Wise (2005) emphasize, articulation is inherently dynamic: in any given context, certain social formations persist while others evolve or dissolve. Here, the Paiwan house-based social structure offers a solid foundation in traditional cultural logic, yet its flexibility makes it a potent vehicle for articulating the heterogeneous. Placing this analysis within broader discourse on place-based epistemologies, the present study examines how the social structure of the Lalebaq tribe supports the cultivation of articubility. Meanwhile, NTTU-HISP’s core operational logic of “co-exploring theory and practice with local communities” (Tsai & Hsieh, 2018) provides an institutional platform through which both parties strategically enact the processes of articulation and disarticulation described by Clifford. Thus, this study repositions articulation and disarticulation not as fixed outcomes but as dynamic processes through which the capacity for reconnection—what this paper terms ‘articubility’—is activated. While articulation emphasizes the dynamic process of linking heterogeneous elements, articubility foregrounds the potential and conditions that make such linkages possible by interrogating the structural foundations and limits of articulation.

An Ethnography of Local Articulation in the Lalebaq Tribe

The Multiple Faces of the ‘House’ in the Millet Harvest Festival

Social relations in Paiwan society are neither fixed nor absolute; rather, they are assembled through scenes of situated knowledge practice. To understand how articubility takes shape in the Lalebaq tribe, this section examines different forms of the millet harvest festival and analyzes how sasusuwan / civaivaigan, when grounded in house-based relations, reflect diverse interpretations of ‘place’ within the community. Through participation and observation, this study explores how residents of Taiban community articulate identity through kinship, tribal, and community affiliations across different contexts, revealing a shared logic of community heterogeneity.

Traditionally, the millet harvest festival marks the end of the agricultural cycle. Once the final millet sheaf is harvested, traditional leaders conduct the kisatja ritual (ki meaning ‘to collect’, satja meaning ‘crops’), in which tribute is gathered and prayers for abundance are offered for the coming year. In Taiban community, leaders perform kisatja based on their respective lineage domains rather than on behalf of the community as a whole—forming a disarticulation from the administrative community structure. Although residents live within the same settlement, households continue to welcome their respective leaders with offerings—typically beverages, millet, and NT$20, of which NT$10 serves as the symbolic ‘seed’ for the following year’s planting. Even when no one is home, the leader and ritual specialist perform the ritual at the doorstep, thus maintaining obligations and relations.

Due to intermarriage across lineages, many households maintain multiple house affiliations and must prepare several sets of offerings for overlapping kisatja rituals. Despite the community’s collective conversion to Christianity, many households continue to participate materially in the ritual, enacting kakudan through the circulation of goods. Whether performed or not, kisatja thus reconstitutes dynamic house-based relations through sasusuwan / civaivaigan. However, political, economic, and religious transformations are reshaping the ritual. As traditional agriculture declines, leaders increasingly grow ritual millet themselves and apply for government subsidies to purchase pigs for traditional foods such as avay (millet cakes). As a result, kisatja has gradually shifted from a collective public ritual to a more privatized social action.

To sustain kakudan, the Taiban Youth Association has begun securing public funding to organize an inter-lineage joint harvest festival. They invite traditional leaders, residents, and political representatives, and mobilize young people to return from neighboring communities, thereby reframing ‘Taiban’ as a shared ‘home’. While traditional leaders continue performing kisatja within their own domains, the young people open tribal boundaries through joint ritual activities, using shared space and kinship ties to construct an imagined ‘community’ that transcends tribal limits.

During the event, community elders host cultural workshops to teach young people to butcher pigs, weave garlands, and prepare traditional foods. Returning young people participate in rituals, re-entering Paiwan collectivity through embodied experience and reconnecting with cultural roots. In the evening, residents dressed in traditional attire gather at the community center, seated according to their house name. Young symbolically carry leaders into the venue, where residents, neighboring communities, NGOs, and government representatives enjoy performances by elders and children. On the surface, this appears to be a community-wide celebration; in fact, it is a process of disarticulating traditional and state structures and rearticulating locality through kakudan, with the house at its core.

As residents expressed:

“The most beautiful thing in Paiwan culture is kakudan.”

“What we plant no longer has value—kakudan is what we have left.”

“These things matter. I’ve been recording them so the children will know what to do.”

“This is a journey connecting past and future… preserving fading sentiments and kakudan, along with our diminishing identity.”

However, the joint festival has also sparked debate: some call for a return to tribal political frameworks to restore traditional autonomy; others argue that the community should serve as the new basis of public life across lineages. While these perspectives differ, both aim to disarticulate state governance structures and reimagine collective life after resettlement. Yet, because articulation is inherently generative, marked by tension and compromise, power inequalities emerge alongside.

Although kakudan sustains inter-house social relations, it also becomes a field for status display and competition. Under contemporary political and economic pressures, tribute—once an obligation—has become symbolic capital that leaders must actively secure. Rituals now depend on government subsidies, financial capacity, or social networks. Some non-traditional leader households, by mobilizing political, economic, and organizational resources, seek to claim ritual authority—challenging established hierarchies. Meanwhile, disputes have arisen over land and authority between relocated lineages, criticism of unauthorized ritual performances by non-leader families, and contestation over the meaning of ‘publicness’. These tensions emerge from different spatial imaginaries of ‘precedence’ and varied investments in kakudan.

Contemporary Paiwan society is thus characterized by the simultaneous generation of disarticulation and collective revaluation of kakudan. In an ever-shifting spatial-temporal context, ‘publicness’ is both a contested symbol and continuously redefined through social practice. Under these circumstances, this paper further examines how the Lalebaq tribe redefines and enacts publicness across multiple social domains—and how such processes lay the foundation for articubility.

Cultural Curricula: Weaving Local Heterogeneity

Defined by inter-house relationships, kakudan embodies a form of shared memory that orients collective consensus and continuity in Paiwan communities. Under neoliberal pressures, kakudan enables the recomposition of tradition, generating new forms of community through continuity and adaptation (Appadurai, 1996; D.-S. Chen, 2018). Drawing on the symbolic inclusivity of the millet harvest ritual, NTTU-HISP collaborated with local residents to activate shared imaginaries and reengage ancestral frameworks of relationality. While contemporary understandings of sasusuwan/civaivaigan may differ from traditional meanings, they function similarly to what Benedict Anderson (1991) famously termed ‘imagined communities’—not fictional constructs, but deeply embedded modes of collective sociality. Thus, revisiting the past becomes a strategic means to clarify contemporary enactments of kakudan and envision possible futures. For instance, wedding rituals continue to invoke ancestors to affirm marital alliances, thereby reaffirming social hierarchy and cultural continuity (Hsiao, 2019). Tradition, in this sense, is generative. Oral histories of citronella cultivation in the 1960s demonstrate that even ‘non-traditional’ crops shaped local culture through seasonal labor and collective rituals, reinforcing cross-generational ties. This affirms the arguments of Huang Hsuan-Wei (2022) and Huang Ying-Kuei (2016) that local responses to global transformations must be grounded in cultural plurality rather than singular models.

If kakudan is understood as culture—both tacit and embodied—then imagined memory must be grounded in concrete practice. Building on this, NTTU-HISP and Lalebaq young people extended ritual sentiment into courses on Paiwan craft, oral history, and social memory. Through workshops, archival reconstruction, and intergenerational learning, they fostered local agency and mended historical ruptures. Moving from ‘Indigenous knowledge’ to ‘Indigenous ways of knowing,’ these efforts exemplify both disarticulation and rearticulation as methodological approaches. Drawing from Fienup-Riordan’s (2000) concept of ‘conscious culture’, kakudan is both memory and method. Through embodied cultural practice, young people reconnected with land, kin, and responsibility, making ‘the house’ a site of cultural regeneration—looking backward as well as forward.

The first step in the collaboration between Lalebaq young people and NTTU-HISP was a genealogy reconstruction workshop using household registers from the Japanese colonial period. This not only allowed participants to understand the kinship system but also revitalized ancestral authority and ritual context. By cross-referencing colonial documents and oral histories, participants redrew inter-house relationships. These records—though produced by colonial governance—have now become tools of Indigenous reclamation. Led by young people, community projects have used these archives to reconstruct genealogies, map ancestral domains, and restore shared memory. Through this work, fragmented lineages are pieced into a shared historical map, supporting social reconstruction as the community shifts from a tribal polity to an administrative community.

Here, genealogies are not only tools for relationship repair but also reveal power dynamics. Some noble houses use them to affirm claims of kakudan and territorial precedence; others use genealogical branching to construct cross-house alliances. However, the politics of ‘precedence’ complicates this work. While the Lalebaq young people and NTTU-HISP promote broad participation, they remain attuned to these tensions—such as when some participants withdrew during genealogy reconstruction to avoid replicating house hierarchies. The case of the C house also shows that even with clear ancestral authority, their status remains vulnerable to processes of adoption and lineage decline, demonstrating institutional flexibility. Ultimately, genealogies become spaces to resist state segmentation while confronting internal competition. The challenge lies in reweaving fractured relations without reifying inequality. With the goal of cultivating articubility, actors actively trace the evolving logic of kakudan, exploring how house-based relational networks are renegotiated under contemporary political and spatial conditions.

Combining genealogical mapping with action-based curricula, Lalebaq young people and NTTU-HISP encouraged critical reflection on kakudan—not only as a local relational system but as a framework for contemporary social agency. To activate this network, they invited Tsai Cheng-Liang, a researcher of the Amis community in Dulan, to present on ‘Domestic nation-building the Dulan way’—demonstrating how the Amis have integrated the age-set system with state-sponsored community associations to form dual-track governance. Through festivals and collective action, they reinforce communal bonds. Tsai stressed that Indigenous communities must not only preserve tradition but cultivate new capacities to survive in modernity. He encouraged Lalebaq young people to inventory local knowledge and external expertise to build sustainable futures. Inspired by the Dulan model, Lalebaq participants reflected on their own structures. While the Paiwan house-based hereditary system may appear rigid, it also contains adaptability. Yet, state-imposed administrative boundaries erode traditional authority. In Taiban community, multiple traditional leaders must coexist within a single administrative unit, complicating youth coordination.

Youth organizations, once central to collective labor, now experience fragmentation due to blurred roles. The contemporary youth association is tasked with serving both tribal and community levels, yet diverging household expectations and shifting responsibilities complicate this mandate. In Taiban, the youth association is currently dominated by Lalebaq members, raising concerns about uneven cross-tribal participation. In response, the youth association president convened a meeting where opinions diverged: some advocated maintaining a unified organizational structure, while others suggested dividing by house due to uneven participation. Ultimately, the youth association dissolved and was reconstituted as a coalition—each house now operates independently while collaborating on public affairs. This reorganization shows how Paiwan young people are using kakudan as a flexible framework to redefine collectivity. Rather than strictly adhering to state-imposed labels such as ‘Taiban community’, they reinforce house affiliation while challenging tribal boundaries. Through the inclusive logic of ‘the house’, they are constructing a new vision of public life that transcends both houses and tribal lines.

Within the Laleba tribe, multiple understandings of place shaped by kakudan compel young people to continuously negotiate the boundaries of tribal and community-based public life. The spread of Christianity has further complicated this, as the church emerges as another site of public participation. Young people belong both to traditional and church organizations, creating a division between ‘ancestral’ and ‘church’ domains. While the church does not forbid participation in the millet festival, it remains cautious toward ancestral rituals like kisatja, limiting cross-group interaction. Many elders, however, continue to support kisatja as a crucial expression of hierarchical relations. To address these divides, NTTU-HISP introduced the elder-centered logic of kakudan, recognizing elders as embodiments of house relationality who can use kinship ties to reconnect young people across organizational divides.

To initiate this, Lalebaq young people and NTTU-HISP collaborated with a local senior care center, inviting young people from different religious backgrounds to care for elders while practicing local knowledge. They brought in Pinnan cultural historian Huang Chun-Ming and Sin-Yuan artisan Lin Chia-Lun to lead a leathercraft workshop, using hunting knowledge and leatherwork to build community cohesion. Huang shared forest knowledge, explaining how hunting practices connect land, ecology, and kakudan-based social relations—drawing from his childhood experiences in Taiban. Lin guided young people in assisting elders to make leather pouches, shifting caregiving from an institutional service to embodied, intergenerational care centered on vuvu (a Paiwan term for elders/grandchildren). The workshop later expanded to traditional hunter’s hat making, involving both youth associations and church groups. Such activities became shared moments that transcended divides of faith, mobility, and education. As young people expressed, “The cultural health station is not just a facility—it’s where our ancestors gather,” and “Becoming a hunter is not just about the gun—it’s about learning in a broad way.”

Through kakudan as a shared value system, these practices seek to bridge generational and spiritual divides, strengthening internal cohesion. Elders become the fulcrum of heterogeneity, allowing young people to explore alternative modes of belonging. While Lin initially questioned the cultural specificity of hunter’s hats, as Clifford (2013) argues, cultural authenticity lies not in objects but the social processes they activate. Through creative practice, returning young people reentered home-based lifeworlds and reconnected with land-human relations. Hat making thus became a catalyst for contemporary kakudan rearticulation, further shaping house-centered community life. As local livelihoods decline and young people migrate for education and work, the spatial and relational structures that sustain kakudan are increasingly disembedded. To avoid rendering ‘the transmission and practice of kakudan’ an empty slogan, the key lies not only in strengthening traditional values but identifying modes of rearticulation compatible with modern life.

To strengthen local agency, Lalebaq young people and NTTU-HISP invited Gao Su-Chen-Wei from Yaping Strategy Consulting to share ‘Diversified forms of Indigenous tourism’, drawing from her planning of the East Coast Tribal Work-Exchange Program. As a Paiwan herself, she shared organizing experiences across ten communities, inspiring participants to apply kakudan-oriented thinking to local tourism. Participants reflected on how industries could serve as platforms for cultural continuity. Gao noted that while work-exchange tourism may not yield immediate economic benefits, sustained planning that integrates place-based knowledge with professional marketing can turn tourism into a mode of ‘traditional practice’ adapted for contemporary needs. Yaping has developed immersive tourism projects such as the Eight Chiefs Challenge and Kisatja Mystery Game, which reconstruct traditional leadership relations while responding to state restructuring of hierarchy systems. NTTU-HISP used this case to guide participants in identifying which elements of kakudan must be preserved and which adapted, fostering flexible traditional modernity.

While such initiatives cannot immediately resolve economic challenges, they provide crucial starting points for reimagining local livelihoods. Abstract academic discourse often fails to translate into practice; thus, Lalebaq young people and NTTU-HISP grounded their efforts in Indigenous agency, identifying relational subjects across people, land, and economy to explore cross-disciplinary modes of articulation.

Multiplicity of Community Subjectivities and the Strategic Rearticulation of Place

Given the multifaceted nature of community subjectivities, this study begins by analyzing the social interactions enacted during the millet harvest festival as a means to clarify the grounded configurations of publicness in contemporary Lalebaq. This approach does not treat cultural activities as isolated ends; rather, it frames them as situated interventions that reveal the contextual conditions under which the capacity for rearticulation—the articubility—can emerge. Through collaborative development of cultural curricula, the university and local residents collectively explore the generative question “Who are we?” not merely to affirm identity, but to cultivate articubility as a situated potential to generate new forms of collective life.

The strategic reactivation of kakudan (house-based relationality) embodies such a practice-based articulation. Here, local actors and NTTU-HISP employ kakudan as both method and medium for (1) reconstructing internal relational networks and (2) recalibrating shared ethical horizons. Crucially, this effort does not presume a homogenous or pre-existing ‘community’, but instead foregrounds the production of community through tensions, collaborations, and negotiated boundaries. Articubility thus emerges as a relational capacity grounded in everyday practice—a capacity to hold open the possibility of reconnection, even amid unresolved historical and contemporary conflicts.

As Huang (2022) reminds us via Geertz’s paraphrase of Kierkegaard, “Life must be understood backward but lived forward.” Similarly, the memories activated by local people and NTTU-HISP are not invoked to reconstruct a static past, but to actualize their connective potential within present action. Through rituals, educational workshops, and heritage-based economic initiatives, kakudan becomes a living infrastructure through which articubility is enacted across education, governance, and economic experimentation. In this regard, articubility offers a way to move beyond rhetorical cultural revitalization toward operative frameworks for action.

This model can resonate beyond Lalebaq. As Chou (2018) suggests, university–community relations often move from point-to-point interactions toward networked and multi-scalar collaborations. Such a trajectory lends itself to adoption in other Indigenous and rural contexts where historical fragmentation and contemporary resource asymmetries persist. Indeed, articubility offers a scalable model, in which cultural governance, local revitalization, and university praxis converge around the shared project of rebuilding relational infrastructure.

Moreover, positioning articubility within broader discourses of regional revitalization and cultural governance highlights its cross-disciplinary relevance. In Japan’s Chiiki Okoshi initiatives and Taiwan’s cultural empowerment programs, interventions often stall when they presume the community as a unitary subject. Articubility, however, emphasizes tending to internal plurality, relational tensions, and adaptive capacity—precisely the elements necessary for sustainable place-based transformations. In this regard, it facilitates a conceptual bridge between Indigenous relational ontology and contemporary governance frameworks, offering a nuanced alternative to deficit-based development paradigms. Finally, the tensions revealed in Lalebaq—between inter-lineage competition and shared ancestral obligations, between ritual continuity and modernist demands—highlight a fundamental premise: connection is never predetermined. Articubility thus becomes both analytical lens and political praxis. It calls upon universities, government agencies, and local actors to shift from resource delivery toward cultivating the latent capacities for reconnection.

In conclusion, this study argues that articubility—rather than articulation alone—constitutes the generative condition for Indigenous-led community reconstruction and place-based futures. While previous studies of articulation often emphasize the outcomes of heterogeneous assemblages and the intertwining of internal and external forces, the present research takes a different approach. By closely examining the cultural logic and lived practices of Lalebaq, this study asks: why is articulation possible at all in certain communities? It suggests that, despite the presence of fundamental cultural traditions that appear unshakeable, communities often harbor specific mechanisms of social elasticity that enable them to respond creatively to shifting conditions.

In the case of Lalebaq, this elasticity is embodied in kakudan—a relational framework that is at once a deeply rooted traditional value and the very mechanism that renders tradition dynamic. Kakudan provides a flexible structure through which genealogical relations, collective responsibilities, and shared identities may be differently reactivated, negotiated, and repurposed across time. In other words, it is not only the content of tradition that matters, but also the relational infrastructure that allows tradition to become actionable and adaptive.

By foregrounding this capacity to enable reconnection—articubility—this study offers a praxis-oriented framework with relevance far beyond the Paiwan context. It calls attention to the relational infrastructures that sustain local life in an era of global precarity, underscoring that true revitalization lies not in restoring a frozen past, but in reweaving fragmented inheritances into adaptive and relational futures—even across difference. This perspective invites further comparative inquiry into how other Indigenous and rural communities activate their own cultural elasticity in the process of revitalization and opens pathways for broader international dialogue on relational forms of community resilience and transformation.

Funding

Funder: Science and Technology Council

Grant Number: NSTC 113-2420-H-143-003 -HS3

Recipient: Taitung University