Introduction

In 2023, National Football League quarterback Aaron Rodgers made headlines when he completed a darkness retreat at Sky Cave Retreats, an exclusive darkness retreat center in Southern Oregon. During his stay, Rodgers lived in a 300-square-foot subterranean room devoid of all light for four days. His only contact with the outside world was with Scott Berman, the owner of Sky Caves. Before entering his retreat, Rodgers explained that he hoped to “have a better sense of where I’m at in my life” (Thai, 2023). For Rodgers and other darkness retreat clients, living in complete darkness removes all external distractions, allowing for an extended period of deep introspection with the goal of achieving self-acceptance and inner peace. Client testimonials describe experiencing an intensely emotional journey leading to acceptance of themselves and spiritual awakenings (Bakshi, 2023).

Outside of its commercialization, darkness immersion is a spiritual practice used in various religions around the world. For example, in Tibetan Buddhism, experienced practitioners utilize prolonged darkness immersion as a sensory technique to induce unusual visions (Hatchell, 2014). In Daoism, dark environments like caves are regarded as ceremonial spaces (Kohn, 2000). In Irish folklore, caves are associated with supernatural beings. Ancient Egyptians viewed caves as passageways to the underworld (Moyes, 2012). Caves also serve as underworld passageways for Mayan societies, for whom caves are where their Ancestors originated, and where one can commune with deities who govern rain (Spenard, 2021).

Across what is now referred to as the settler empire of the United States, caves are ceremonial spaces for Indigenous peoples and were engaged with strict protocols. Ancestral Indigenous cave practices are a part of location-based knowledge systems, and homeland caves are culturally significant sites to be protected and preserved. Indigenous religions have been targeted for destruction by settler colonial society, and Indigenous religious spaces are stolen and desecrated. To steal and occupy Indigenous lands, settler colonial nation-states attempt to eliminate Indigenous societies through physical and conceptual elimination. Physical elimination includes mass murder campaigns, carried out by settler-governments or private settler citizens who are funded by settler colonial governments. In the Southeast, as Native American studies scholar Michelene Pesantubbee (2005) details, European colonizers purposely incited regional violence by creating alliances with certain tribes to cause inter-tribal battles. Forced Removals of Tribal Nations also remove Indigenous people from their homelands to clear them for settler occupations.

In addition to physical elimination, Indigenous cultures and religious practices are targeted for elimination. (D. F. Brown, 2013; Glenn, 2015; Wolfe, 2006; Kēhaulani Kauanui, 2016). Indigenous homeland-based religious practices are components of knowledge systems that evidence Tribal connections to land bases, so they are eroded through assimilation policies such as boarding schools (1860-1960) which forced settler religion and language upon kidnapped Indigenous children, preventing them from maintaining their cultural practices and languages through abuse and violence (Lomawaima, 1994; Newland, 2022). Native religions and cultures were outlawed for 95 years by the Department of the Interior’s Code of Indian Offenses beginning in 1883 until the passage of the American Religious Freedom Act of 1978 (Price, 1883, American Indian Religious Freedom (Joint Resolution) Public Law 341, 1978). Indigenous religious spaces are also consistently threatened because they are often un-built, natural geographies, and their sacredness is consistently unacknowledged by settler governments. Many sacred sites are located on dispossessed homelands, many of which are located on national and state park lands, opening them up to violations from tourists. Sacred sites are also located on ‘public’ lands and are therefore open to mining claims and extractive industries (McNally, 2023). Cave artwork sites are especially vulnerable to destruction by vandals and graffiti. Due to the sacredness of homeland caves, and the ongoing need to protect tribal sacred sites, this paper will not provide location details about culturally significant cave sites. Furthermore, this article expands upon Indigenous studies scholarship that considers the wide-ranging impacts of Indigenous knowledge commodification, especially religious practices, for settler-controlled markets.

Ancestral cosmologies of Southeastern Tribal Nations view the dark zones of caves, the point of a cave where no external light can reach, as a source of power because they are the passageways to the underworld. 16,000 caves are located across Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia (Lieffring, 2020). Ancestors of the contemporary Muscogee (Creek), Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole, Coushatta, and Yuchi Nations traversed the dark zones of these caves, sometimes up to ten miles (Crouch, 2022). Caves were illuminated by applying mud balls to the end of torches crafted from burning cane stalks (Ancient Art Archive, 2022). Artwork motifs placed in the dark zones of caves symbolized transformation as the viewer journeyed deeper into the caves. Mud glyphs, petroglyphs, and pictographs adorn cave walls and depict entities associated with transformation and the underworld, one of three worlds from Mississippian cosmology, a shared belief system practiced throughout the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States between 800 to 1600 CE. Mississippian cosmologies divide the world into three levels: the upper sky world, the middle plane where humans, plants, and animals reside, and the lower world. The sky world and the lower world are governed by powerful entities, and all three worlds are circled by the path of souls, or what is commonly known as the Milky Way (Faulkner & Simek, 1996).

As a researcher who is also a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation, this paper analyzes the commodification of darkness from an American Indian and Indigenous studies perspective. The utilization of dark cave environments for ceremonial purposes is an ancestral knowledge rooted in the Chickasaw Homeland and disrupted by genocidal U.S policy. Beginning in 1837, Chickasaw relationships with caves and other significant sites were disrupted by the tribe’s Removal from its Homeland of Mississippi, Tennessee, Alabama, and Kentucky (Chickasaw Nation, n.d.). For the Chickasaw Nation and other Tribal Nations, Removals from our homelands resulted in profound and unquantifiable losses, including separation from Homeland caves and detailed understandings of how our Ancestors used them.

The Chickasaw Homeland is more than material resources; it is home to other-than-human relatives. Chickasaw Ancestors understood and related to Homeland ecosystems through complex knowledge systems maintained through cultural practices and inter-generational teachings (Gibson, 1971). However, we have been separated from our Homeland and its caves for four generations. Because of this separation, much of our understanding of how our Ancestors engaged the cave networks of our Homeland has yet to be renewed because of the Removal and other genocidal policies implemented by the US government. Understanding our Homeland environments is especially critical for Chickasaw arts and culture production because our ancestral visual culture developed within our Homeland, especially from its extensive cave networks.

The multidisciplinary field of American Indian and Indigenous studies addresses topics and concerns that are relevant to today’s Tribal Nations, including the revitalization and protection of Indigenous knowledge and cultural practices (K. Tsianina Lomawaima, 2007). The protection of Indigenous knowledge is critically relevant to projects of Indigenous homeland returns and re-engagements for Tribal Nations that have contended with forced Removals from lands. In settler capitalist enterprises, Indigenous cultural practices and philosophies are viewed as commodifiable resources (Whitt, 1995). Because the commercial darkness retreat market is an emerging topic of study, scant literature investigates how the darkness retreat industry might be claiming, extracting, and transforming Indigenous knowledge and cultural practices that engage darkness immersion into commodities for settler markets. To attract clientele, the website marketing content of some darkness retreat centers frames their offerings as culturally or spiritually ‘authentic’ and unique location-based experiences. The website content of darkness retreat centers frequently includes images of various Eastern symbols, such as Buddhas and lotus flowers. Some websites feature references to North and South American Indigenous cultures through descriptions of cave ceremonies by various Indigenous cultures from Colombia to Australia, as well as images of objects and people connected to these cultures. The biography sections of darkness retreat websites frame the owners as ‘expert’ practitioners of darkness immersion and other healing rituals derived from Eastern and Indigenous cultural practices. Given that most darkness retreat companies are owned by white Americans and Europeans who advertise to affluent, white wellness tourists, the expanding darkness retreat industry warrants a critical Indigenous studies analysis.

To address this gap, this article first presents findings from a qualitative visual and textual analysis of 15 darkness retreat websites. Three specific types of settler colonial discourses are identified across the darkness retreat websites included in the study: wilderness, authenticity, and the mastery of Indigenous knowledge by the white settler citizen. Each discourse is frequently used in historic and contemporary settler colonial cultural productions that frame Indigenous land as wilderness available for settler possession, and white settler citizens as heroic explorers and tamers of the wilderness. By identifying the use of settler colonial discourses by the darkness retreat industry, this article argues that the darkness retreat industry transforms darkness into a product for individual consumption through the process of cultural imperialism: the commodification of Indigenous spiritual practices for settler capitalist markets (Whitt, 1995). Then, interview findings are presented from preliminary research into individual Chickasaw community member responses to the darkness retreat industry. Interviews with two Chickasaw Nation community members who are scholars of Chickasaw history and culture explore current understandings of darkness as an ancestral communal Chickasaw practice. The interviews reveal cultural understandings of darkness that emphasize the importance of community benefits over individual benefits, and protocols that restrict ceremonial knowledge to only specifically selected individuals who are specially trained to be practitioners of darkness ceremonies.

The Significance of Darkness to Indigenous and Global Cultures

The nighttime sky is fundamental to the human experience, yet the darkness of the nighttime and cave dark zones continues to be framed as spaces of danger in Western Culture. Social and cultural geographer Tim Edensor (2013) articulates that despite increasingly illuminated urban environments, Western feelings about darkness remain informed by Christian allegories that darkness brings evil, and the light of God can vanquish this evil. Edensor examines how enlightenment discourse deploys the metaphor of light for knowledge, yet this knowledge is obtained as a method of control and domination wielded by the Western male subject over territories to be colonized. For example, British colonial discourse referred to Africa as the ‘Dark Continent,’ associated with ‘primitive’ cultures which European colonizers could ‘civilize.’ Sociologist Murray Melbin (1978) draws parallels between American feelings about the darkness of night and the Western frontier of the 1870s-1880s; both are associated with dangerous, unpopulated ‘wilderness’. Accordingly, the advent of artificial lighting was celebrated as a triumph of masculine, civilizing logics and technologies over nature. For example, Edensor (2017) points out that Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Italian author of the Manifesto of Futurism (1909) argued that it was desirable to ‘kill’ the natural illumination of the moon with superior man-made illumination because moonlight is associated with traditional, nature-based mythologies. Literary scholar Cinzia Sartini Blum (1996) articulates that in Marinetti’s Futurist worldview, the moon is a symbol of feminized nature, which can be vanquished with masculinized technology. Today, artificial illumination functions as a form of power through its role in the surveillance of policing spaces, and in producing images of domesticity and patriarchal gender hierarchies (Edensor, 2017; Bille & Sørensen, 2007; Garvey, 2005).

Nocturnal human activities were previously overlooked in archaeology but are now a growing research area. Archaeologists April Nowell and Nancy Gonlin’s (2018) edited volume gathers research into nocturnal social worlds across diverse societies, including those from North America, South America, Africa, India, and Polynesia, to illustrate the ways that darkness and the nighttime informed economic, ritual, and social practices of ancient societies. Nowell and Gonlin (2021) also analyze the material cultural objects used for specific types of labor performed at night, illustrating how nighttime is an active space for social and economic transformations. Archaeology of the nighttime sky also engages the field of Indigenous astronomy, which privileges Indigenous science, cultural relationships, and knowledge systems of celestial bodies that appear in the night sky (University of Calgary, 2025). Indigenous astronomy knowledge systems range from Indigenous oceanic navigation knowledge to Indigenous architecture (Diaz, 2021; Reilly & Thompson, 2004).

Cultural meanings of darkness in Indigenous and Eastern societies reflect expansive gender roles beyond Western paternalistic logics. Prior anthropological and archaeological interpretations of Indigenous and other non-Western material cultures overlooked female power and the nighttime. Southeastern Tribal Nations are matrilineal societies in which women hold central social power and responsibilities, and gender expressions expand beyond the imported Western gender binary of male and female. Archaeologist Susan M. Alt’s (2018) analysis of Siouan oral traditions, artworks found at the Mississippian mound metropolis of Cahokia, and artworks applied to the walls of a cave 50 miles east of Cahokia shows previously overlooked correlations between the night sky, the moon, and darkness with female reproductive powers (Alt, 2018). Behavioral scientist and environmental humanities scholar Neha Khetrapal (2023) examines similar correlations between the moon and the deity Śakti in the material culture and architecture from the Indus Valley civilization of eastern Pakistan and north-western India. However, female power represented by the moon stories was subordinated by Aryan myths about a male sun god.

In addition to the nighttime sky, archaeological research investigates the cultural and political uses of subterranean spaces. A collection of essays edited by Holly Moyes (2012) reveals the global uses of subterranean environments as ceremonial spaces and manifestations of diverse cosmologies including ancient Egyptians associated caves with the underworld, (Smith, 2012), neolithic and Bronze age cave use in Crete, Greece (Tomkins, 2012), caves as sacred spaces during the Upper Paleolithic and the Bronze Age in the Apulia region of Southeast Italy (Skeates, 2012).

Research on Eastern North American caves initiated in the 1960s (Watson, 2012). Mississippian dark zone artwork research initiated after a 1979 ‘discovery’ by recreational cavers of a site in Eastern Tennessee (J. F. Simek et al., 2013). Scholars believe that Southeastern cave artworks symbolize animal guardians who escort souls through the underworld to the path of souls, and figures in states of transformation. They are concentrated in a region of Tennessee located far from large Mississippian settlements, possibly evidencing that caves were religious pilgrimage destinations (J. F. Simek et al., 2013). Similarly, James Brady and Cristina Verdugo’s (2025) edited volume on Mesoamerican subterranean sacred spaces suggests that built and natural subterranean caves were sites of Mayan pilgrimages. The significance of cave dark zones to contemporary Tribal Nations is a critical area of scholarship that is best led by tribal research departments. Non-native scholars are beginning to collaborate with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma, and the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma to research and conserve their homeland cave artworks (Carroll et al., 2019).

Darkness and Tourism

Critical examinations of tourism related to dark environments is a new area of research primarily concentrated on tourism related to the dark sky movement. In response to increasingly illuminated nighttime environments. The impacts of light pollution from urban development on wildlife is an urgent ecological concern. The global dark sky movement is composed of interdisciplinary initiatives and interventions by scholars, artists, and activists to restore nighttime ecologies (Dunn & Edensor, 2023). National parks are becoming destinations for viewing astronomical events. Communication studies scholar Dwayne Avery’s (2023) analysis of an astro-tourism marketing campaign identifies discourses of American frontier mythology, framing national parks as empty wilderness. America’s vacant national parks were made possible through genocidal campaigns waged against Indigenous peoples (Walter, 2023).

Critical examinations of darkness retreat tourism remain limited; therefore, the darkness retreat industry is not formally categorized within tourism literature. Therefore, this article situates darkness retreat centers within holistic health and spiritual tourism markets, overlapping facets of wellness tourism, another emerging area of tourism research. Tourism scholars Jane Ali-Knight and John Ensor (2017) identify the subsectors of wellness tourism as including yoga, meditation and spa activities as well as holistic and spiritual experiences. Wellness tourism consumers travel to destinations for activities that improve their own physical and mental health. The industry’s target clientele is middle to upper class with disposable incomes and the time to pursue leisure activities (Ali-Knight & Ensor, 2017). Wellness tourists also increasingly seek holistic health products (Martins et al., 2023). Holistic health is achieved through activities that treat mind, body, and spirit.

For holistic health tourists, the destination is an important component of holistic tourism offerings. The tourist desires exotic experiences only available through travel (Ali-Knight & Ensor, 2017). A growing sector of holistic health tourism is spiritual tourism in which clients engage in “a quest for enlightenment.” Spiritual tourism products commonly include components derived from Eastern medicines, philosophies, and practices. Spiritual tourism is pursued by those with or without religious affiliations who desire spiritual experiences derived from religions they perceive as exotic (Ali-Knight & Ensor, 2017). Darkness retreats appeal to holistic health and spiritual tourists because they are unique, destination-specific holistic health experiences said to improve physical, emotional, and spiritual health.

Testimonials authored for online news sites by darkness retreat center clients explain how their prior patronage of retreats that evoke Indigenous ceremonies led to their interest in darkness immersion (Bakshi, 2023). The utilization of dark environments within Indigenous and other global cave ceremonies does impact human physiology. Cave archaeology scholars Daniel R. Montell and Holley Moyes (2012) draw from behavioral and cognitive science to understand human experiences in caves. Caves produce a disorienting psychological response due to darkness and a lack of orienting directional environmental cues such as stars and the moon. Human spatial cognition is impaired, especially in labyrinth-like cave systems. Long periods of dark zone sensory deprivation may result in extreme psychological experiences such as delusions, hallucinations, anxious feelings, or memory loss. However, short periods of darkness might facilitate productive reflection and relaxation (Montello and Moyes, 2012). In alignment with Montello and Moyes’ findings, interdisciplinary research explores the impacts upon human cognition and emotions when experiencing complete darkness. Dunn and Edensor (2023) draw from psychologists and social scientists to show how affective properties of darkness include openness to relationship building, intimacy, and “a feeling of freedom, self-determination and reduced inhibition . . .” Darkness immersion may also inspire risk-taking and creativity (p. 23).

Darkness retreat center websites claim that extended darkness immersion changes one’s brain chemistry. After 24 to 48 hours of complete darkness immersion, the brain releases extra melatonin, resulting in deep rest and extended periods of sleep. Following the sleep stage, the brain releases chemicals that can trigger hallucinations. Some clients report that these hallucinations lead to spiritual and emotional epiphanies. In the field of psychology, darkness immersion is considered one type of ‘chamber rest’, a sensory deprivation therapy used to treat psychological disorders. The effects of darkness immersion on a patient is a niche area of psychology research. University of Ostrava psychologist Dr. Marek Malůš is one of the few researchers who are coordinating studies with darkness immersion centers. Malůš finds that there are therapeutic effects of darkness immersion for patients (Malůš et al., 2016). Malůš’s research conducted at Villa Mátma, a darkness immersion center in the Czech Republic, finds that staff there witness how darkness immersion is an effective preventative for diseases like cancers, and metabolic disorders. They also say that it activates sensory awareness, and creativity, and “most notably, regenerates the psyche” (Childs, 2018).

Research on the potential health benefits and dangers of darkness immersion is ongoing, and some psychologists remain skeptical of commercial darkness retreat centers. When discussing Roger’s darkness retreat with ESPN reporter Xuan Thai, Dr. Sarah Meyer Tapia, who is a psychologist and director of Stanford University’s Living Education and Wellness Education programs, expressed concern about the lack of psychological support at darkness retreat centers like Sky Caves. “How [do] they support the psychological safety when somebody’s in there and completely in the dark alone with themselves…and not further damage processes that might not be healthy inside themselves” (Thai, 2023). Tapia, who specializes in mindfulness and meditation, explained to ESPN that while mindfulness can be beneficial to everyone, meditation is not. “There are moments when it’s contraindicated, somebody’s spiraling in a psychotic episode or even a depressive or anxious episode to go inward and sit in that, is kind of to reinforce it” (Thai, 2023). Darkness immersion is an extreme form of meditative introspection through sensory deprivation. Thus, its commercial use outside of medical supervision may be an under-researched area of concern for the field of psychology.

Methods

My qualitative analysis of darkness retreat websites identifies five signs and assemblages from Website text, video, and images. Each of these signs and assemblages correlates with a type of settler colonial discourse: constructing Indigenous land as ‘wilderness’ that is available for settlers to claim, framing of Indigenous people as ‘authentic’ to construct racial hierarchies, and the extraction and commodification of Indigenous spiritual practices by business owners who claim to be ‘expert’ spiritual practitioners. Michael Ball and Gregory Smith (1992) argue that visual representation is related to other cultural arrangements because signs and symbols construct social life. Because company websites function as advertisements for prospective clientele, website content can reveal much about the target clientele and their worldview. A primary technique of an advertisement is to reference commonly held cultural knowledge and associated visual references that prospective clients might already understand (Ye & Kovashka, 2018). Thus, advertisements are assemblages of signs that produce meaning. The material objects pictured in advertisements function as signs or signifiers. The signified are the various meanings that are attached to the material objects pictured within an advertisement by the viewer of the advertisement based upon their knowledge and understanding of the pictured material objects. People can also be paired within an advertisement to draw relational meanings between the two (Ball & Smith, 1992).

To conduct a qualitative analysis of darkness retreat center websites, the meanings of the imagery, text, and video of the websites were analyzed for various pairings of signs. The presence of certain signs, absence of certain signs, and assemblages or pairings of signs and people within darkness retreat website marketing content were then assessed for ways they might evoke cultural discourses used in settler colonial projects. The resulting analysis draws from settler colonial studies, Indigenous studies, and critical tourism studies literature that articulates how settler power operates through the extraction, claiming, and commodification of Indigenous lands, bodies, and knowledge. Capitalism, as settler colonialism’s economic system, requires the theft of both tangible Indigenous resources, such as land, minerals, and objects, as well as intangible Indigenous resources such as labor and intellectual property (Vimassalery, 2013). As a matter of settler capitalism, cultural tourism companies frequently re-produce racializing colonial encounters, exploit Indigenous labor, and commodify Indigenous knowledge with material impacts on local Indigenous communities (D. F. Brown, 2013). Relevant to an analysis of commercialized darkness immersion is philosopher Laurie Anne Whitt’s (1995) frame of cultural imperialism. Cultural imperialism is the commodification of Indigenous spiritual practices by settler companies, a process that secures “absolute ideological/conceptual subordination” (Whitt, 1995, pp. 171–172). Cultural imperialism is an oppressive power structure that mines Indigenous creativity, undermines Indigenous political power, and generates profit for settler capitalists. By assessing the signifiers that are used by darkness retreats to situate ‘darkness’ within the spiritual practices of a racialized ‘Other,’ this investigation traces how cultural imperialism is enacted within the nascent commercial darkness immersion market.

Website Content Analysis Findings

Wilderness

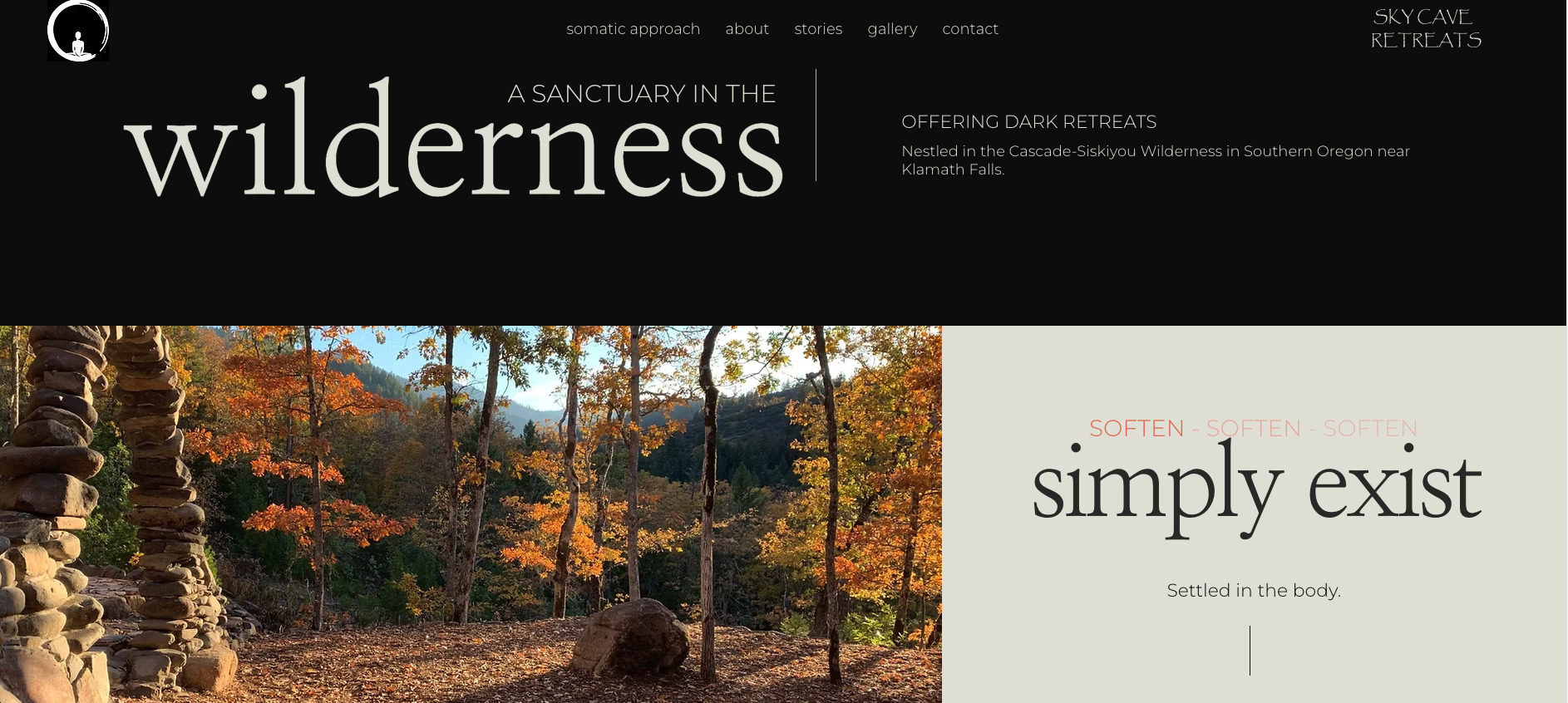

Images and descriptions of wilderness saturate darkness retreat center websites. Photographs featuring nature and remote wooded areas surrounding darkness retreat centers are the most common theme across the websites in this study. The terms ‘wilderness’ and ‘Nature’ are also common words used in website text. For example, Figure 1 is a screenshot of a content block on the homepage of the Sky Caves retreat center. A landscape photograph pictures a roughly constructed stone arch on the left of the frame. To the right sits a small boulder in the middle of a clearing surrounded by orange fall foliage lit by afternoon sunlight. Thickly forested mountains unfold in the vista beyond. Above the photograph, the header text reads, “A sanctuary in the Wilderness.” The word wilderness is written in large font. The caption text to the right of the photograph reads, “Offering Dark Retreats, Nestled in the Cascade-Siskiyou Wilderness in southern Oregon near Klamath Falls” (Sky Caves Retreats, n.d.). Notably, no specific address is listed for the retreat center. The omission of a business address retains the center’s aura of exclusivity and presence as a natural component of the wilderness, rather than a company with a mailing address.

While ‘wilderness’ is prominent in the Sky Caves website photographs and text, regional tribal histories that include the displacement of Tribal Nations from their homelands do not appear on darkness retreat websites. The Sky Caves retreat center consistently uses wilderness photographs with no people featuring its grounds, evoking feelings of solitude and personal healing through immersion in ‘pristine’ nature (Sky Caves Retreats, n.d.). However, locations like the Cascade-Siskiyou Wilderness Preserve were made possible by the forced displacement of Indigenous people from their homelands to reservations. The Klamath Falls region is part of the homelands of the Klamath Tribes, which include the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin. In 1864, after “decades of hostilities with the invaders,” an area of over 23 million acres was ceded by the tribes in a treaty with the US government (The Klamath Tribes, n.d.). The tribes were then confined to a reservation as stipulated by the treaty. The absence of the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin from the Sky Caves website text is an example of the repeated use of nature as wild spaces in which tourists can journey by darkness retreat center websites.

Critical geographers argue that the idea of ‘wilderness’ is co-constitutive with whiteness because wilderness connects to the logic of terra nullius, thus framing land as available for white ‘discovery’ and possession. Wilderness signifies Indigenous absence and allows white settler citizens the opportunity to ‘discover’ the land as they traverse and recreate in this wilderness. Additionally, whiteness and nature are both socially constructed together because Indigenous people must be evicted from the land to create ‘wilderness’, a violence never articulated by discourses of wilderness mythologies. Wilderness as a socially constructed space frames Native land as empty and available for claiming by settler society, and spaces like national parks are dedicated as ‘untouched’ areas of nature available for exploration (Kobayashi et al., 2011).

Across darkness retreat website content, the term ‘journey’ is almost as common as ‘wilderness.’ Within settler cultural productions, spaces of ‘wilderness’ facilitate frontier hero journeys. Frontier myths tell of ‘heroes’ who fight on behalf of ‘civilization’ in ‘savage wars’. In these myths, a white settler enters Native land, framed as ‘wilderness’, masters Indigenous knowledge, and then uses Indigenous knowledge against Indigenous people. English and American studies scholar Richard Slotkin (1998) analyzes frontier mythologies in literary accounts of travel and adventure in the late 1700s-1800s to find that frontier hero stories were circulated to blame Native Americans as instigators of their own genocide. Frontier narratives justify white settler violence as necessary for American ‘progress’ (Slotkin, 1998, p. 13). Often contradictory, these narratives evoke romantic notions of unspoiled nature while justifying capitalist development enabled by genocidal policies (Slotkin, 1998).

Frontier mythologies served settler capitalist expansion throughout American history by redirecting the frustrations of the laboring class from the economic and political elite towards a convenient scapegoat: an Indigenous enemy whose ‘primitive’ culture is a threat to American modern society (Slotkin, 1998). Frontier stories were used by Industrial Revolution-era politicians as a strategy to secure a subservient labor population by portraying Indigenous people as a common enemy to white settlers, conveniently diverting working-class frustrations away from economic and political holders of power. Early 18th-century narratives celebrated ‘American-heroes-as-Indian-fighters’. This trope later transformed into nineteenth-century ‘wilderness hunters’ like Daniel Boone. “As the man who knows Indians,” frontier heroes like Boone enforce the boundaries between “worlds of savagery and civilization,” and can either act as interpreters between races or as lethal soldiers of ‘civilization’ who can turn Indigenous knowledge against Indigenous peoples (Slotkin, 1998, pp. 15–16).

Darkness retreat center websites position their locations as destinations that offer clients a space to journey into the dark wilderness of their own mind. Journeying into darkness is a consistent theme in the videos, and texts of the websites analyzed, echoing the settler-colonial narrative of the wilderness hero journey. Darkness is visually symbolized with black backgrounds in the design of many websites. Photographs of the night sky and dark spaces lit only by a candle are also plentiful. The most sophisticated websites analyzed are produced by the Sky Caves, and Sacred Tree companies. They feature highly produced dramatic videos that include scenes of caves, forests, night skies, people silhouetted seemingly by the moon, and the owners of the centers discussing darkness immersion as it connects to Eastern and Indigenous cultures. Throughout Western art history, particularly in Western film, darkness is a symbol of danger, evil, or a foreshadowing of negative events. Media studies scholars Charles Forceville and Thijs Renckens (2013) analyze cinema’s conceptual metaphor of the daytime equating to good and the nighttime equating to evil. Darkness in film is deployed to evoke negative emotions, following human biology, because human vision is poor in darkness, contributing to feelings of vulnerability. (Forceville & Renckens, 2013). Sky Caves and Sacred Tree videos do not explicitly frame darkness as dangerous. However, client testimonials describe feelings of fear, and overcoming this fear led to their feelings of personal growth (Sacred Tree, n.d.; Sky Caves Retreats, n.d.). Darkness in this application symbolizes an unknown space symbolic of an internal, psychological world.

Authenticity and Racial Hierarchies

Darkness retreat companies authenticate their offerings by picturing local Indigenous people. For example, the Hermitage Center, located at Lake Atitlan in Guatemala, uses images of locals and the land to create consumer desire for their retreats, which range from 2,000 to 3,000 USD. Figure 2 is a screenshot from the ‘About’ page of the Hermitage Center. The page is titled ‘Spaceholders of the Hermitage’, and identifies staff members with photographs and captions describing the types of labor each employee provides the center with. The photograph pictures the owner Severin Geser, who is Swedish, sitting with dog and a brown-skinned man, unnamed in this caption. As you scroll down, the header ‘The Hermitage Team’ is positioned above pictures of employees and descriptions of their roles. The nameless man from the photograph with Geser is now pictured with his brother, and they are identified as Francisco and Felipe, although there is no specification of which name belongs to which brother. The text paired with their photo explains that “they have built this place with their own hands and honed their skills over the years” (The Hermitage, n.d.). Two other employees are also highlighted on the page: Francisca Leja, the chef, and Tony Cox, the driver. The final section of the page highlights the center’s temazcal, which is a Mayan sweat lodge that is available to clients (The Hermitage, n.d.).

The photographs combined with the captions that specify the name of the white owner while excluding the name of the groundskeepers signals a racialized labor hierarchy in which the white business owner is named, and provides the center’s leadership and intellectual labor, while the darker-skinned employees are not clearly named and are the manual laborers. From the photographs and names that are either included or excluded from the text, we can glean a colonial pattern of racial construction. Critical whiteness studies scholars define racial constructions and discourses that normalize whiteness as violent systems of power (Baldwin et al., 2011). Eighteenth century race thinking was predicated upon the notion of biological difference, positioning whiteness as normative and thus at the top of the racial hierarchy of difference (Baldwin et al., 2011). As settler colonial studies scholar Patrick Wolfe (2006) articulates, an “organizing grammar of race” (p. 387) is operationalized by settler societies to deem themselves the rightful owners of Indigenous lands. This organizing grammar of race is drawn from Christian Enlightenment definitions of the human as distinct from nature with agency and reasoning capabilities (qualities also deemed as masculine). By this reasoning, ‘modernity’, the highest level of humanity, was achieved through agriculture because progress depended upon the overcoming of nature. This human, as geographer Andrew Baldwin (2022) shows, actively shapes history and the world through intellectual endeavors (Baldwin, 2022).

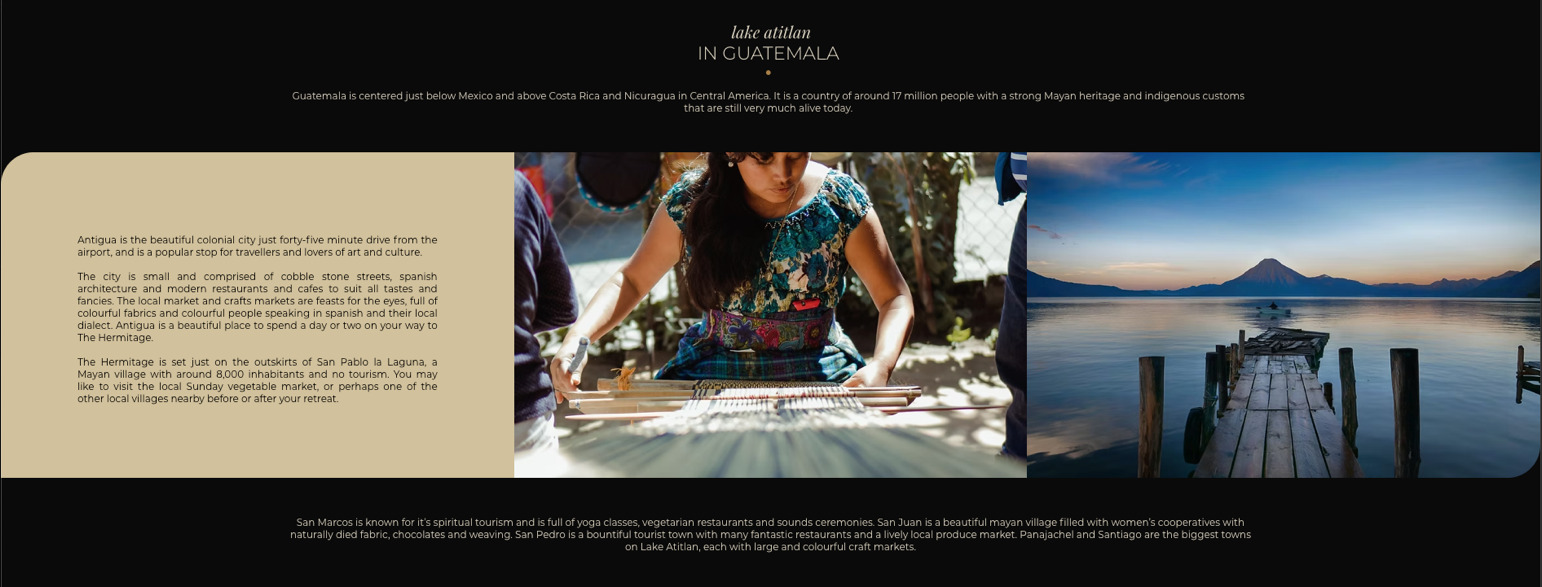

The Hermitage Center highlights its location at Lake Atitlan to authenticate its offerings. Images and captions frequently reference the local Mayan community to position the Hermitage Center as a remote and "authentic’ destination. For example, Figure 3 is a screenshot from the ‘Lake Atitlan’ page of the Hermitage Center’s website. The arrangement of content pictured in the screenshot is composed of an image of a Mayan woman weaving and a picturesque scene from Lake Atitlan. To the left of the photographs is a caption that emphasizes culture and a lack of other tourists:

The Hermitage is set just on the outskirts of San Pablo la Laguna, a Mayan village with around 8,000 inhabitants and no tourism. You may like to visit the local Sunday vegetable market, or perhaps one of the other local villages nearby before or after your retreat (The Hermitage, n.d.).

The pairing of a Mayan weaver who is unnamed, with a landscape image reinforces the racialized association of Indigenous people with wilderness. To reiterate, wilderness in the settler imaginary is a space occupied by Indigenous peoples who are sub-human parts of the natural world. Unlike the modern human subjects of 18th-century racial thinking, Indigenous people do not enact agricultural practices that fully dominate the land. Although this logic is false, as many Indigenous societies hold sophisticated agricultural knowledge, it is a racializing discourse used by settler societies to undermine Indigenous entitlement to their land (Bhandar, 2018).

The caption text next to the photograph frames the ‘Mayan village’ of San Pablo la Laguna as existing outside of modernity. The presumed presence of 8,000 Mayan villagers and the absence of other tourists constructs San Pablo la Laguna as untouched by outside cultures, despite the text explaining it as only a 45-minute drive from the “beautiful colonial city” of Antigua. Because no other tourists are presumably present, the clients of the Hermitage Center can enact their own colonial ‘discovery’ of the lake and its culturally ‘authentic’ Mayan village. An analysis of tourism marketing in the Riviera Maya region of Mexico by tourism scholar Denise Fay Brown (2013) finds that tourism companies frame Mayan peoples as part of the location’s exotic past when they are actually contemporary people. Brown argues that “tourism is primarily a capitalist ideology” (D. F. Brown, 2013, p. 194), which constructs its product from the landscape and racialized representations of Indigenous people. Tourism marketing converts Mayan spaces and bodies into a consumable ‘otherness’(D. F. Brown, 2013, p. 193). These mythologies frame the tourist as a justified presence in the landscape and an “explorer into the past,” “exploiter into paradise,” or “expedition into the primitive” through performances of colonial encounters with Indigenous people and lands (D. F. Brown, 2013, p. 200).

The focus on the remoteness of The Hermitage Center, because it is adjacent to a Mayan village, is intended to activate the tourists’ desire for culturally authentic destinations. The Lake Atitlan text and imagery combinations follow the pattern of categorizing Indigenous people as either ‘authentic’ or ‘inauthentic’ by settler society. A primary marker of ‘authenticity’ is to be unchanged, or frozen in time. Any innovations and utilizations of contemporary technology and materials are viewed as ‘inauthentic.’ Gender and Indigenous studies scholar Mark Rifkin calls this relegation of the Indigenous person to the past ‘colonial time’. Colonial accounts of history, portray Indigenous people as stagnant and incapable of engaging in contemporary life to enact sovereignty over their lands. Tribal sovereignty is framed as antiquated and pre-modern because it poses a threat to settler political systems based on the occupation of stolen tribal homelands. (Rifkin, 2017). Colonial time allows settler society to justify the exclusion of Indigenous people from contemporary political decisions, especially ones concerning lands and resources required for settler capitalist expansion.

The Commodification of Darkness as Indigenous Knowledge

Darkness retreat center owners frequently describe themselves as experienced practitioners of Indigenous and Eastern spiritual practices. The owners, who are mostly white males, commonly describe life-changing encounters with spiritual practices outside of their origin cultures during young adulthood. One example is the Sacred Tree retreat centers, located in Gowerton and Swansea, Wales, which offer mixed retreat services. The owner, Greg Manning leads clients through darkness retreats and other ‘Shamanic’ ceremonies derived from various Indigenous cultures. The website advertises ‘ceremonies’ retreats, and trainings for shadow stalking, Chinese medicine, energy healing, shamanic healing, movement medicines, nutrition, and Kambô ceremonies in which practitioners ingest a hallucinogenic substance derived from tree frog poison (Sacred Tree, n.d.).

The narrative that darkness retreat center owners use to describe their journey to darkness immersion practitioners follows the frontier wilderness hero story arch. The discovery and subsequent mastery of Eastern and Indigenous healing practices are narrated as dramatic events in their life trajectory. After they gain enough proficiency in the healing practices, they are called to return home country and repackage it for sale to other Westerners. On the Sacred Tree ‘About’ page, Manning’s professional credentials are described in the below passage:

Greg first began his journey with shamanism in his late teens, arriving at South American shamanism in 2000 when he was 22. Since then he has travelled to South America - learning there and in the UK from several different teachers in a host of practices, including the Kambô from Giovanni Lattanzi in 2013. Kambô and other shamanic practices are now at the core of his healing services…Between 2014 and 2016 he studied energy healing in the style of Barbera Ann Brennan. Since 2014 Greg has drawn upon the intricate energetic wisdom of Chinese medicine to enhance his existing energy practices. This forms a significant part of his work with the Kambô secretion and energy healing work (Sacred Tree, n.d.).

In addition to darkness retreats, Manning sells ceremonies and shamanic training derived from diverse Eastern and Indigenous cultures. Within settler capitalist markets, settler subjects symbolically replace the Indigenous body with their own by performing and consuming Indigeneity or ‘playing Indian’, a practice that historian Philip Deloria (2022) traces from the Revolutionary War to the 1970s. Performances of Indianness through costumes, activities, clubs, and societies shore up national identity and reconcile anxieties over social change.

Sacred Tree’s events and shamanic training allow clients to “master” Indigenous ceremonial healing practices by playing Indian. In an embedded video on Sacred Tree’s website, Manning describes how his center’s darkness immersion products are inspired by shamans and Daoists:

To take the inspiration from the people who are most familiar with the darkness that has used it in the spiritual sense, and this is the shaman’s, uh, the, the Daoists who use it to help it connect with the void, the lucid dreamers for this extended hypnogogic hypnopompic periods that we have either side of sleep because of this meditative state, um, that people are more connected to their creativity (Sacred Tree, n.d.).

Sacred Tree frequently correlates darkness retreats with shamanism. For example, Manning asserts that “Darkness is a very powerful shamanic medium which can create an altered state of reality and a plethora of physical, emotional, psychological and spiritual effects.” Terms such as “Shaman” and “Shamanism” are generic and lack culturally specific context yet are commonly operationalized in for-profit tourism contexts. Sacred Tree’s “Shamanic” products are examples of cultural imperialism. To reiterate, cultural imperialism is defined by Whitt (1995) as the marketing and commoditization of Native spirituality. The unsanctioned appropriation of Native spiritual practices by settler-owned companies erases cultural specificity, context, and ignores cultural protocols. Whitt specifies that cultural imperialism is a type of social control that perpetuates settler capitalist profits while sanctioning settler political power and authority. As a practice of intellectual and cultural property theft, cultural imperialism prioritizes settler corporate profits by subordinating Native political authority and rights to protect cultural knowledge (Whitt, 1995).

Cultural imperialism is also a process of conceptual assimilation that deploys the settler property laws of terra nulla, the concept of empty land available for claiming, and ‘public’ domain to privatize Indigenous land and immaterial property for the benefit of settler capitalism. First, Western notions of public domain are applied to Indigenous knowledge making “the (material, cultural, genetic) resources of Indigenous cultures” (Whitt, 1995, p. 8) common property. Then, these are declared common property, and any member of the public may transform them into commodity form as demonstrated by Sacred Tree’s product descriptions. Descriptions of Sacred Tree’s darkness retreats are explicitly correlated with non-Western cultures to appeal to Sacred Tree’s clientele: “Deep Darkness retreat allows you to access the immersive experience practiced for centuries by Native Americans, Tibetans, Aztecs, Egyptians, Yogis, Buddhists, Tantrists, Taoists, Lucid Dreamers and Creatives into the depth of the luminescence of your true essence” (Sacred Tree, n.d.). This language frames the darkness retreat as a pathway to the client’s “true essence” which is achieved by taking and utilizing non-Western cultures. The spiritual practices of non-Western cultures are thus free for claiming and use by paying clients.

Chickasaw Perspectives on Darkness, Caves, and Commercial Darkness Retreats

Darkness is an element of Chickasaw Homeland geographies and ancestral Mississippian cosmologies. However, the forced Removals of the Chickasaw Nation and others under the US government not only physically eliminated Indigenous people from the land but also disrupted Indigenous knowledge of cave systems and their cultural meanings. Like other Tribal Nations, the Chickasaw Nation dedicates significant resources towards the preservation, research, and renewal of Chickasaw history, culture, and arts. Today, the Chickasaw Nation facilitates initiatives to renew community relationships with and understandings about our Homeland cultural sites. Ongoing programming includes research by tribal historians, archaeologists, and anthropologists, and group Homeland tours for tribal citizens, sometimes referred to as pilgrimages or heritage tours (LaDonna L. Brown, personal communication, November 19, 2025). Because the darkness of the nighttime or of cave environments is an ancestral philosophy that is anchored within the Chickasaw Homeland, further examination of its various meanings and relevance will be valuable to our community and future generations. Community-driven research beyond the scope of this article can engage Chickasaw artists and knowledge keepers to explore if and how our creative community is thinking about and engaging ancestral darkness philosophies today.

Findings from other Southeastern Tribal Nations have already yielded insights about the importance of ancestral dark zone practices in homeland caves. Extensive cave artworks evidence that during the 1800s, homeland caves were spaces of sanctuary for Cherokee people to conduct ceremonies away from white settlers, and even provided hiding places for Choctaw people who refused to leave their homelands. Cave archaeologist Jan Simek (2021) has carbon-dated 92 cave artwork sites ranging from 10,000 B.C. to at least 1828. The year 1828 is inscribed with Cherokee syllabary on a cave wall in Alabama in an area that is a part of Cherokee homelands. Cherokee Nation archaeologists and linguists interpret the inscription as describing a stickball ceremony, the sacredness of the cave, and how the cave site was safe from white settlers who opposed Cherokee religion (J. Simek, 2021). In addition to the 1828 inscription, Cherokee Nation archaeologists and linguists are researching and interpreting numerous artworks and writings applied to their homeland caves (Carroll et al., 2019). Their findings will be significant to scholars from other Southeastern Tribal Nations because the inscription is dated shortly before the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 by the US government, which evidences how homeland caves were culturally significant spaces until the Removal period. The Indian Removal Act targeted the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole nations, resulting in deadly relocations from their homelands in the southeast to Indian Territory, now the state of Oklahoma (Glenn, 2015).

In addition to cave sites as spaces for conducting ceremonies without threats from settlers, they also offered a way to evade Removal. Caves offered sanctuary for Choctaw people during the period. In a 1973 interview, Louise Willis (Mississippi Choctaw) is asked about how the Mississippi Band of Choctaw came to be separated from the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. In reply, Willis recalls a story told to her by her grandfather, who explained how some of the Choctaw people who refused Removal to Indian Territory escaped by hiding in a cave located near Nanih Waiya, a large mound structure made of earth. Nanih Waiya is central to Choctaw origin stories and is sometimes known by the Choctaw as “Mother Mound” (L. Brown, personal communication, November 19, 2025). The mound itself has a cavern with a smaller entrance (Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, 2024). An oral history by Issac Pistonatubbee recorded in 1901 explains that the mound is where the Muscogee, Cherokee, Chickasaw, and Choctaw peoples each emerged:

Yes, they said that God wanted them to stay, so they stayed there. But when the White man was going to take all the Choctaws to Oklahoma, some of the people that wanted to stay ran back, it’s about two miles back and you’ll find the Nanih Waiya—if you walk, you know, it’s about two miles back to the Nanih Waiya Cave. They ran away and they hid, and these other Choctaws went on to Oklahoma. They ran away and hid and that’s where they stayed most of the time. It’s near water, the cave. (Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, 2024)

Willis specifies that “the cave is a different place from the mound, and the Indians used to run two miles from the White people” (Willis, 1973, p. 26). The mound, ancestral village site, and the cave Willis refers to were donated back to the Mississippi band of Choctaw Indians and the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, and access to them is managed by the Mississippi Band of Choctaw (Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, 2024).

Indigenous knowledge connected to homelands encompasses political and social formations within the land, and because of this, it is targeted by settler colonial projects. Therefore, the extraction and commodification of Indigenous knowledge by cultural tourism industries should be assessed for potential harms by the contemporary Indigenous communities this industry extracts from. The following analysis is a summary of initial findings from semi-structured interviews with Lokosh (Joshua D. Hinson), PhD, the executive officer for the Chickasaw Nation Language Preservation Division, and LaDonna Brown, the Chickasaw Nation Director of Anthropology. While this community research is ongoing, I have identified three initial differences between darkness-related ancestral Chickasaw cultural practices, and commodified darkness immersion: Individuality, practitioner training protocols, and physical movement.

Individuality

A darkness retreat is an individual experience, allowing one to separate oneself from one’s web of relationships and responsibilities to others. This use of darkness for the individual contrasts with Chickasaw culture. Hinson states that “the individual is the least important in our culture” (personal communication, January 6, 2025). Ancestral cave ceremonies were likely conducted for the benefit of the whole community. Spirituality, and ceremony are communal practices that strengthen relational responsibilities to one another. For example, stomp dances, which are practiced at night by whole communities to mark important times of the year are a community-based embodied knowledge. Muscogee author Jean Chaudhuri theorizes the connection between stomp dances and the nighttime: “the stomp begins at night—represented by the color black, the night is a time for reflection, the prelude to creation, and the beginning of a new journey” (Chaudhuri & Chaudhuri, 2001, p. 54).

Hinson shares that in Chickasaw culture, the darkness of night may be significant because in Ancestral Mississippian cosmologies, the underworld flips at night and is accessible at night. In our migration story, our Ancestors had to travel a long distance east to a new Homeland. To protect them along the way, Aba’ Binni’li,’ the Creator, gave them Ofi’ Tohbi’ ishto, the Big White Dog. When the people had to cross the Mississippi river, some believe Ofi’ Tohbi’ ishto drowned in the river and was lost. Below the surface of the water is where the spirit world exists, and that is where Ofi’ Tohbi’ ishto resides, so at night when the worlds flip, Ofi’ Tohbi’ I̱hina’ (the White Dog’s Road) is seen in the sky. The road is what we call the Milky Way today. Ofi’ Tohbi’ ishto was selfless and sacrificed himself to protect the Chickasaw during their migration (L. J. Hinson, personal communication, 2025). LaDonna Brown specifies that “We believe him to be a real dog, but he had special healing properties provided by Aba Binili” (L. Brown, personal communication, November 19, 2025).

Practitioner Training Protocols

Darkness retreat center owners self-identify as expert practitioners of healing and ceremonies. In contrast, only specially trained Chickasaw people would have entered caves. Brown explains that “a normal citizen would not go into a cave unless they went into a ritual—only certain persons could go into caves like medicine men.” Training and preparation would have required specific protocols and processes for selected people (personal communication February 10, 2025). Because caves may have been passageways to the underworld for Chickasaw Ancestors, they are not spaces of personal healing. Mississippian cosmologies divide the world into three levels: the upper or sky world, the middle plane where humans, plants, and animals reside, and the lower world (also associated with under the surface of bodies of water). Powerful entities govern the sky world and the lower world, and the path of souls circles all three worlds, or what is commonly known as the Milky Way. Researchers of Mississippian iconography hypothesize that caves as pathways to this lower world were adorned accordingly with lower-world symbols (J. F. Simek et al., 2022). For Brown, Chickasaw elders are the most important primary sources for communally held knowledge and practices. Therefore, it is difficult to specify the exact meanings of cave artworks and beliefs about darkness. For example, the belief that the worlds flip during the nighttime, allowing for underworld access through caves may “…have been a Chickasaw belief a long time ago, but our current elders would say that they have never heard of this” (electronic communication, 2025). Underworld associations with caves is a shared consensus by researchers of Mississippian iconography who examine different mound builder group’s philosophies. Scholarly findings are shared and discussed at the Mississippian Iconographic Conference, organized by Texas State University. In 2013, the conference was hosted by the Chickasaw Cultural Center and has since facilitated further collaborations and consultations between Chickasaw researchers and the Mississippian iconography studies field (Texas State University, 2013).

Brown shares that certain practices in dark environments have negative associations, and there “are certain taboos about the darkness that we adhere to.” Referring to Indigenous Southeastern belief systems, Brown clarifies that “someone who was conjuring up creatures from these [dark] places were practicing evil intentions and spirits. They were not good people; they were practicing bad medicine” (L. Brown, personal communication, November 19, 2025).

Personally, these are not any retreats that I would go to, going to sleep at night and saying my prayers at that time is good for me. Culturally speaking, when our Ancestors went into caves, they were drawing signs and symbols on the walls which were manifestations of our understanding of spirituality. There is archaeological evidence that torches were used in those caves…There may have been some type of darkness healing and meditation, yet it is not revealed in the archaeological record in our historic Homeland. We cannot say that it did not happen because we weren’t there (L. Brown, personal communication, November 19, 2025).

Physical Movement

A darkness retreat lacks physical movement. It is conducted within one room where the client is isolated from the outside world. In contrast, Chickasaw ceremonial and cultural practices enact intentional movement through environments such as moving through a cave as our Ancestors did, or the way we stomp dance today in specific pathways around the dance grounds. These practices of physical movement are performed communally and engage the surrounding environment with specific intentions. Specific cultural practices that involve inter-generational community members also engage a metaphorical movement of knowledge through time. Mvskoke critical geographer Laura Harjo (2019) defines cultural practices like stomp dances as kin-space-time envelopes. Building from the geography term space-time envelope:

practices of kinship and knowing the world yield an imaginary that connects with many forms of kin, sites, and temporalities… [and that]…An Indigenous kin-space-time envelope considers ancestral practices that we draw upon to renovate, reinvigorate, and sustain our bodies, psyches, livelihoods, and communities. (Harjo, 2019, p. 28)

For example, the act of listening to stomp dance songs is a kin-space-time envelope. Harjo (2019) articulates that the act of listening to these songs brings us thoughts of both Ancestors and future kin. Another kin-space-time envelope is star gazing, which Harjo (2019) describes as “observing the same stars as our Ancestors” (p. 31). Both actions, listening to songs and looking at stars, replicate the actions of Ancestors. However, because we bring our own lived experiences and contemporary understandings to them, they take on meanings unique to our own standpoints. Like stars and stomp dance songs, the caves of our Homelands might offer future Chickasaw people felt knowledge as future generations re-connect with our Homeland spaces.

Conclusion

Wellness tourism enterprises may seem innocent, but tourism is often permeated by settler colonial logics. While leisure economies are not usually associated with overt violations of Indigenous rights, wellness tourism follows patterns of settler entitlement to Indigenous lands and resources, including knowledge and cultural practices. The utilization of Eastern darkness immersion practices and Indigenous cosmological framings of caves by darkness retreat companies point to patterns of cultural Imperialism, and a settler entitlement to Indigenous resources that extends to Indigenous land.

Three consistent themes emerge from a website content analysis of darkness retreat center website imagery, design, text, and video: wilderness, authenticity, and the commodification of Indigenous knowledge. Wilderness is a socially constructed space within settler cultural productions and is denoted as being occupied by Indigenous people who are not a part of white settler civilization. Therefore, it is significant that the most common imagery used by darkness retreat center websites are photographs of nature. Darkness retreat centers frequently highlight the wild, natural surroundings of their locations. Images of wilderness are paired with video narratives and textual descriptions of darkness immersion as a journey. Absent from darkness retreat websites are mentions of the Indigenous people whose homelands the center is located on, especially if that community was dispossessed of that land. The conquering of these wilderness spaces is achieved by heroes from settler-authored frontier mythologies in which white settler protagonists embark upon a journey through the wilderness, encounter Indigenous people, learn and master their knowledge, and then return with this knowledge to white settler civilization. The protagonist is a hero and symbol of the settler project because he can use Indigenous knowledge against Indigenous people.

Images of Indigenous people and descriptions of darkness immersion as Indigenous spiritual practices are used by darkness retreat companies to portray their centers as offering culturally authentic products. Indigenous people are framed as untouched by white civilization through an emphasis on the remoteness of the center’s locations, as well as textual and photographic references to unnamed local Indigenous people. The arrangement of photographs with text on website pages that highlight the locations of some centers communicates racial hierarchies in which the white owners are racially superior and Indigenous staff are inferior manual laborers whose value lies in their exotic appeal to potential clientele. Within settler-colonial racial logics, the label of ‘authentic’ is used to frame Indigenous people as unable to evolve and engage in modern, contemporary life. Authenticity labeling practices serve settler colonial projects by excluding Indigenous society from engaging in political negotiations to protect their land and assert their status as sovereign, modern, nations.

Cultural imperialism operates to reinforce settler property regimes and racial hierarchies while flattening the community specificity of Indigenous knowledge and culture. When aspects of Indigenous spirituality are extracted by outsiders and then commodified for profit, the settler logic of entitlement to Indigenous land and resources is perpetuated. The owners of darkness retreat centers are primarily white settler males who present themselves as ‘experts’ of spiritual practices from cultures outside of their own. They then compete with one another to sell these spiritual practices to tourists. By doing so, they ‘play Indian’ for profit.

After presenting the website content analysis findings, three key themes emerge from interviews with Chickasaw scholars. First, darkness retreat center offerings emphasize personal benefits while in Chickasaw culture the health of the community as a whole is the most important. For Chickasaw Ancestors, darkness might have been a communal knowledge connected to location-specific cultural practices. While settler-owned darkness retreat companies package darkness as a medicine to heal individuals, Chickasaw scholars explain that in our world views, the darkness of the nighttime, or caves, are shared environments, accessed with other humans. These environments are also shared geographies with other-than-human relatives, including plants and animals. Cave environments might also be spaces for supernatural beings. Knowledge and ceremonial practices are communal, and the collective well-being of the community is more important than personal benefits. Second, darkness retreat center owners appoint themselves as expert ceremonial practitioners. An egregious example of this is the Sacred Tree center that offers shamanistic training for customers. In Chickasaw culture, ceremonial and spiritual knowledge is only held by certain people, and the dark spaces of caves were too powerful and dangerous for those not specially trained and equipped to navigate. Finally, in a darkness retreat one is contained within a small room, whereas Ancestors of the Chickasaw Nation moved through the dark environments of caves and used illumination from cane torches. Physical movement is associated with ceremonies and cultural practices that connect to the nighttime and caves. Unlike the settler capitalist commodification of darkness, darkness within Chickasaw world views is just one aspect of cultural practices and philosophies connected to specific Homeland places.

Indigenous knowledge systems as ongoing practices disrupt settler mythologies and geographies. Protecting Indigenous knowledge from commodification requires awareness of interlocking systems of power: colonialism, capitalism, and the gendered and racial hierarchies these systems require. Settler colonial systems are inscribed upon Indigenous lands and bodies through laws, borders, and their violent enforcement. Unraveling and unsettling the perceived normativity of oppressive hegemonies is a spatial and temporal process requiring careful looking forward, looking backward, and deep listening to Indigenous cultural practitioners.